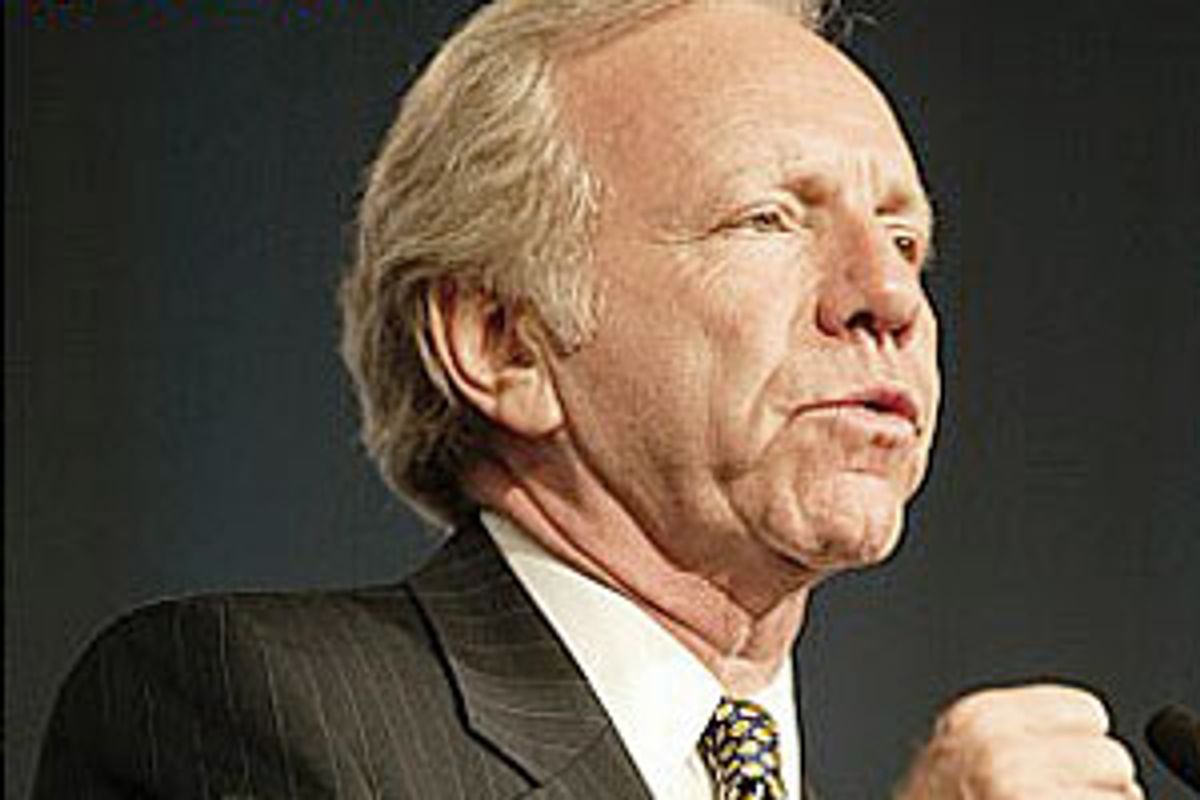

No current Democratic politician so maddens the party's progressive grass roots as Connecticut Sen. Joseph Lieberman. And it's not just that he supports the war in Iraq. Other high-profile Democrats, including Hillary Clinton, have declined to repudiate the Iraq campaign (or apologize for their votes authorizing it) and haven't lost the support of the Democratic rank and file. The problem with Lieberman is that he has defended not only the war but also the administration's rosy view of it, insisting that things are going well at a time when other hawks -- from Rep. John Murtha to Iraqi dissident Kanan Makiya -- are warning of impending disaster.

Lieberman is now seen as the most important Democratic apologist for the White House, a man who shores up what little credibility the president has left, while undermining his own party and refusing to own up to the debacle Iraq has become. Increasingly, people in his own party want to take him down. As the 2006 midterms approach, some major Democratic funders, despite their dream of reclaiming at least one house of Congress, are prepared to spend a lot of money and energy defeating one of their own.

The question is who the Democratic war on Lieberman would hurt. If successful, it could wound George W. Bush, who would lose his last vestige of bipartisan support, and send a message that Democrats are united against the president's war. But it would also divert resources from races against Republicans, and make at least some hawks feel unwelcome in the party at a time when Democrats need to expand, not narrow, their appeal.

Lieberman's unpopularity among progressives is nothing new. The senator views himself as a maverick, willing to cross partisan lines in the national interest. (He could not be reached for comment on this story.) But liberals see him as gratuitously hostile to his own party and overly generous to Republicans. In the last few weeks, though, anti-Lieberman sentiment has boiled over as the senator has sought to shore up Bush's increasingly vilified Iraq policy.

On Nov. 29, Lieberman sparked the ire of Democrats with an Op-Ed in the Wall Street Journal titled "Our Troops Must Stay." "I have just returned from my fourth trip to Iraq in the past 17 months and can report real progress there," he began. "More work needs to be done, of course, but the Iraqi people are in reach of a watershed transformation from the primitive, killing tyranny of Saddam to modern, self-governing, self-securing nationhood -- unless the great American military that has given them and us this unexpected opportunity is prematurely withdrawn."

A week after his optimistic Op-Ed, Lieberman called for a bipartisan war cabinet to advise the president on Iraq. "It's time for Democrats who distrust President Bush to acknowledge he'll be commander in chief for three more years," he said at a news conference in Washington. "We undermine the president's credibility at our nation's peril." Around the same time, rumors started flying that Lieberman might succeed Donald Rumsfeld as defense secretary next year.

"I don't think there's anyone else on the war who so vocally is ignoring reality and siding with the president," says Eli Pariser, executive director of MoveOn.org. "It's one thing to have the position; it's another thing to poke people in the eye with it."

Jim Dean, president of Democracy for America -- the organization that grew out of his brother Howard Dean's presidential campaign -- echoes Pariser. "To say we're supposed to go along with the president just because he's going to be president for three more years is frankly inappropriate, to put it nicely," he says.

Both Dean and Pariser say their groups would consider funding a Lieberman challenger in 2006. Such an effort would have the support of star Democratic blogger and fundraiser Markos Moulitsas Zúniga, who wrote on his site, the Daily Kos, "And to think, I used to defend the guy. Now, if MoveOn decides to help a challenger in such a primary, I'm behind them 100 percent."

Despite his high favorability ratings in state polls -- 67 percent, according to a July 2005 Quinnipiac survey -- the "dump Lieberman" movement is growing increasingly confident, especially now that Lowell Weicker, the former Connecticut senator and governor, has pledged to challenge the incumbent if no one else steps forward.

"Without a doubt, Joe Lieberman will not be our senator in '07," says Keith Crane, a member of the Democratic town committee in Branford, Conn., and the administrator of the anti-Lieberman Web site DumpJoe.com. "Lowell Weicker can beat him. Joe does not represent Connecticut," he says.

Weicker, a liberal Republican-turned-Independent, is less sanguine about his chances. Lieberman "is very popular in the state," he says. "I realize I'm putting my head on the chopping block. There's just no getting around that he is a popular senator in the state. How that popularity is affected by his continually being the point man for George Bush on the war, I can't evaluate that."

A 74-year-old who walks with a cane, Weicker first announced his willingness to run on Dec. 5 at the Hartford Rotary Club. He evinces little relish for returning to politics. "This is something I would reluctantly do, but only if nobody else will stand up," he says. "I'm not going to give Joe Lieberman a free pass on the war." Weicker's campaign platform would be simple: "Within six months to a year, I want our troops out. Period."

Weicker and Lieberman have a long history. Weicker was a three-term Republican senator from Connecticut until 1988, when Lieberman defeated him by less than 1 percentage point. On foreign policy, Lieberman had challenged Weicker from the right -- the incumbent was considered pro-Castro, and Lieberman garnered the support of Cuban exile leader Jorge Mas Canosa.

With liberal Republicanism becoming oxymoronic, Weicker became an Independent and ran a successful campaign for governor in 1990, leaving after one term amid widespread anger over his introduction of state income taxes. Today he's president of the Trust for America's Health, a nonprofit focused on disease prevention. (He's particularly concerned about avian flu and blames Bush for diverting resources to Iraq that are needed to prepare for a possible epidemic at home.)

Conventional wisdom is that Weicker doesn't stand a chance against Lieberman in 2006, and that he may even open the door to a Republican victory. Because Lieberman is so popular, the GOP isn't planning to field a challenger, but George Gallo, Connecticut's Republican state chairman, told the Hartford Courant, "The dynamics obviously change in a three-way race. There probably would be someone who would want to jump in."

Weicker might have a better shot at beating Lieberman in the Democratic primary. But despite the prodding of local anti-Lieberman activists like Crane, he refuses to join the party.

"Both parties are at fault," Weicker says. "You have the idiotic policy of the Bush administration, which brought us into this war in a disingenuous way, and then you have a bunch of Democrats sitting around agreeing with what happened, or semi-agreeing, or failing to stand up and get counted. So why would I want to be a Democrat? Their silence has been as devastating as Bush's policy. I'll stay right where I am."

That sounds like good news for Lieberman, but at least a few observers see the senator as vulnerable in a general election. "Lieberman's stance on the war is not a politically popular thing here in Connecticut," says Ken Dautrich, a professor of public policy at the University of Connecticut and a close watcher of state politics. "While national polls show that people are marginally against the war, in Connecticut that trend is exaggerated. And that opens up a huge opportunity for someone who wants to challenge Lieberman in a Senate race." Weicker, Dautrich adds, may be just the candidate, as he has shed his negative baggage and remains well known in the state.

If he does run, Weicker could benefit from the same groups that raised money for Howard Dean in 2004. MoveOn, which raised $30 million to fight Republicans in 2004, would be open to backing him. While Pariser emphasizes that no decision has been made yet, his group's members set the organization's priorities, and they're furious at Lieberman. "The amount of concern that we hear from folks in Connecticut about Lieberman on Iraq is mountainous," he says.

Similarly, Democracy for America is likely to support Weicker -- pitting an organization close to the Democratic Party chairman against a Democratic elder statesman. "We would be extremely interested if he were to run," says Dean, who lives in Fairfield, Conn. "He's very principled, a great guy and a free thinker."

Lieberman's liberal opponents insist that challenging the Connecticut senator fits into a broader strategy of fighting for a Democratic majority. They say that by covering for Bush and criticizing Bush's Democratic critics, Lieberman undermines the party in a way that's likely to hurt Democrats in 2006.

"Most of our resources are going to go into the fight to win back Congress in 2006 -- certainly that's a primary focus for us," Pariser says. "At the same time, when people like Lieberman dilute the Democratic brand by saying something that's so out of line with what most Democrats believe, that's a problem, and it's a problem precisely for the people who are trying to win in 2006 and trying to convey to voters a coherent message about what Democrats stand for. We're far from making any kind of decision about what specifically to do in Connecticut, and we would go to our members first if we did. But there's a lot at stake in what Lieberman says."

In confronting Lieberman, MoveOn would be following a strategy similar to that pursued by right-wing pressure groups like Club for Growth, which doesn't hesitate to go after apostate Republicans. In 2004, Club for Growth backed conservative Pat Toomey in his primary challenge to Pennsylvania Sen. Arlen Specter. (Toomey lost and went on to become Club for Growth's president.) This year, the group is supporting a primary challenger to Lincoln Chafee, the Republican senator from Rhode Island.

Club for Growth support is clearly no guarantee of success, but it is useful -- the group raised $22 million for the 2003-04 campaign season. Perhaps more important, the organization and others like it help keep Republicans in line ideologically, resulting in a party with far more message discipline than the Democrats.

But it's not a given that the Republican playbook can work for the Democrats, as the two parties are quite different animals. "I'm not much taken with the mirror-image idea," says Will Marshall, president of the Progressive Policy Institute, the think-tank arm of the centrist Democratic Leadership Council (a group that counts Lieberman among its members). "The Republicans are a truly conservative party. Most Republicans self-identify as conservatives, followed by moderates, and then a smattering of liberals. The Democrats are much more of a coalition party. Moderates predominate. It is not fundamentally a liberal party, although liberals are an important force in the Democratic Party. And for all that, we're still stuck at a 48 percent ceiling."

To the MoveOn/Democracy for America wing of the party, the key to breaking through that ceiling is a clear and unapologetic message, particularly on the war, which a majority of Americans now oppose. They maintain that Lieberman compromises that message and makes winning back Congress more difficult.

Marshall, however, argues that a Democratic majority can only come from making the party more inclusive of moderates and conservatives, and that getting rid of Lieberman would send a signal that those people aren't welcome. He calls the anti-Lieberman campaign "an effort at political intimidation by would-be cyber-commissars."

"I don't understand this impulse to punish and marginalize people that don't toe the activist line," says Marshall, adding, "I don't think many people believe that verging hard left is going to unlock heartland voters or working middle-class white voters."

Yet opposition to Lieberman isn't ideological in the typical right-left sense, activists like Pariser say. Indeed, the labels "liberal," "moderate" and "conservative" only approximate the contours of the conflict. On many issues -- including the environment and abortion rights -- Lieberman is fairly liberal. And the Democratic Party's grass roots have shown a remarkable willingness to embrace ideological differences on core issues in the name of party unity. Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid, a figure beloved by much of the Democratic base for his quietly pugilistic political style, is anti-abortion, as is Robert Casey, who is garnering widespread support for his challenge to Pennsylvania Republican Rick Santorum.

Grass-roots anger at Lieberman isn't even about the war, per se. Rather, it stems from a feeling of betrayal, and of frustration at Lieberman's attempts to cling to a near-dead tradition of bipartisan cooperation on foreign affairs.

Historically, the wise men of the two parties have worked together on issues of war and peace. Lieberman wants to keep that tradition alive.

In response to Democracy for America's protests about some of his Iraq comments, Lieberman wrote: "I have been clear all along that I believe the Bush administration made many mistakes in the run up to the invasion and its aftermath." A few sentences later, he continued, "But I also believe we must be careful not to allow the debate about why we overthrew Saddam and who is responsible for the mistakes to draw our attention away from the national focus we must maintain now to try to find a way to achieve a stable democracy in Iraq. It is crucial for the security of the Iraqi people, for the Middle East, for our nation and for the world."

To his backers, this seems like the mark of a mature statesman. "This has nothing to do with any kind of personal relationship with the president," says Marshall. "It has to do with how Joe Lieberman understands how this country conducts itself when faced with a very difficult war. He is making broader points about bipartisan responsibility. "I think he's being misconstrued as protecting or defending Bush," Marshall continues. "The broader question is how can we get out of Iraq in a way that doesn't leave behind a security debacle for the United States, and that doesn't completely squander the incredible sacrifice made by Americans and Iraqis who are trying to build something better there. Those are the questions that serious people are asking about Iraq."

For Lieberman's opponents, though, the senator's willingness to support Bush as commander in chief doesn't seem serious; rather, it looks like a naive refusal to recognize the rules have changed. As they see it, the Bush era has crushed any sense of nonpartisan national interest. Republicans conflate America with their own party, and their vision for the country includes the destruction of the Democrats and all they stand for. Cooperation with such people in the name of a sadly obsolete kind of patriotism seems suicidal, and optimism designed to bolster national morale just seems dishonest.

"It would be one thing if he conceded that the execution of the war was a disaster because of the way Rumsfeld and others planned it, or basically was in any way admitting how deeply painful the mess that America is in right now is," Pariser says. "But to have him join Bush in telling this sunny story about Iraq that is absolutely not true, it frustrates people more deeply than other candidates have."

Shares