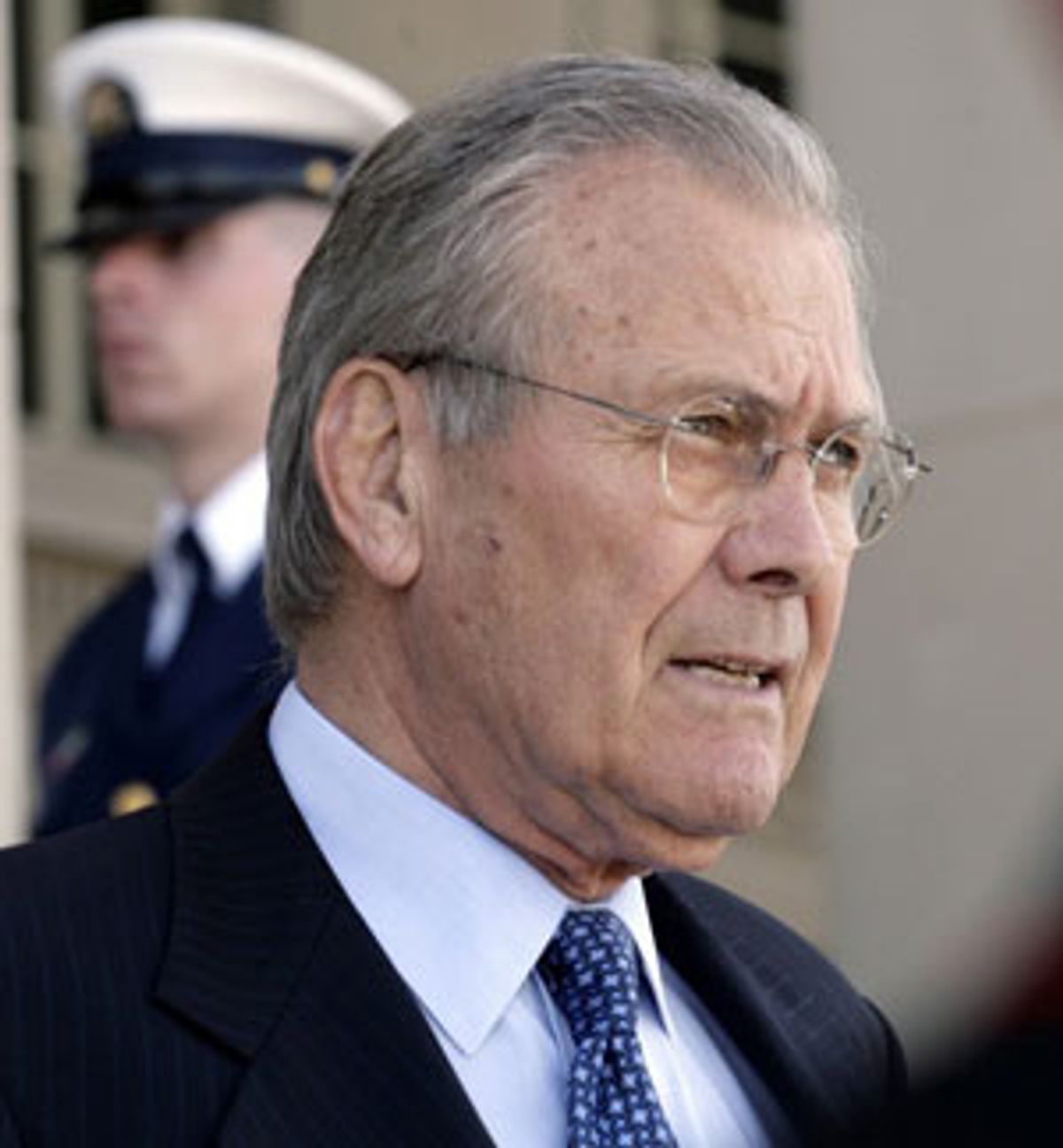

In mid-April, under fire from a half-dozen retired U.S. generals for broad failures in Iraq, the Bush White House dispatched Donald Rumsfeld to the front lines of the American heartland. The secretary of defense appeared on talk radio host Rush Limbaugh's nationally syndicated show to fight back against the decorated military commanders who called for his resignation.

"The sharper the criticism comes, sometimes the sharper the defense comes from people who don't agree with the critics," Rumsfeld told Limbaugh during the April 17 interview. He dismissed the barrage of reproach, suggesting that "the same kinds of criticism" had come and gone during all major American wars, from the Revolutionary War to Vietnam. "This, too, will pass," Rumsfeld said.

But the sharp disapproval aired by the retired generals is, by many counts, extraordinary. Among the charges leveled at Rumsfeld was Maj. Gen. Paul Eaton's conclusion that the defense secretary was "incompetent strategically, operationally and tactically, and is far more than anyone responsible for what has happened to our important mission in Iraq." Maj. Gen. John Batiste, who led the 1st Infantry Division there, said he "served under a secretary of Defense who didn't understand leadership, who was abusive, who was arrogant, who didn't build a strong team." Maj. Gen. Charles Swannack, the former commander of the elite 82nd Airborne Division in Iraq, stressed that culpability for abuses at Abu Ghraib prison leads "directly back to Secretary Rumsfeld."

In interviews with Salon, several retired military commanders said that the unusual revolt against Rumsfeld is both well-founded and increasingly pervasive. From the broad strategic problems in Iraq to Rumsfeld's role in the calamity of sanctioned prisoner abuse, they say the case for his resignation is indisputable, and has the support of many other retired senior officers. One retired commander suggested that the generals' censure of Rumsfeld is especially important because the defense secretary has achieved unprecedented control over selecting the top brass who surround him at the Pentagon.

"Considering the level at which these generals operated, the things they've been saying are a real indictment," said Brig. Gen. David R. Irvine, an Army Reserve strategic intelligence officer who taught prisoner interrogation and military law for 18 years at the Sixth Army Intelligence School before retiring in 2002. "It's not the responsibility of military commanders to decide when the nation goes to war. But these guys are experts -- some of them have direct experience executing the war plans that Rumsfeld developed. So when they say there are serious problems, I would think that Congress and the White House ought to pay attention.

"I don't think I've seen anything like it in my 40 years of service," Irvine added. "Over the last several months I've had conversations with dozens of retired flag officers -- one, two, three stars. I have yet to talk to anyone who is a Rumsfeld fan. The level of disapproval is significant."

At Rumsfeld's side during a press conference last week, Gen. Peter Pace, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, defended the man who appointed him. Pace said that the top brass had "multiple opportunities" to express their views, but that final decisions on military matters were Rumsfeld's. "And when a decision's made by the secretary of defense," Pace said, "unless it's illegal or immoral, we go on about doing what we've been told to do."

Others denied there was rising discontent in the ranks, and suggested that it was out of line for the generals to criticize the head of the Pentagon.

Rear Adm. John D. Hutson, the former judge advocate general of the Navy, believes the criticisms of Rumsfeld by the retired generals are not only appropriate, but necessary. "The captain goes down with the ship. He's in charge, and he's held accountable. This is a proper and important military tradition," said Hutson, who retired from service in 2000 and is now the president and dean of Franklin Pierce Law Center in Concord, N.H. "The lack of accountability up the chain of command has bothered a lot of people for a long time. Frankly, I think this is the gag reflex kicking in. At some point things get bad enough that you have to have a change."

Hutson sees a "spontaneous combustion" behind the firestorm of criticism, rather than a coordinated attack by the generals on Rumsfeld. "A number of leaders seem to be coming to the same conclusions at the same time about how poorly the war is going," he said. "We're allocating precious assets to it that are needed elsewhere, and there is no clear end in sight. In some sense, this is even more fundamental than the torture issue, where a lot of people have had concerns for a long time now. This is about how the whole war is being waged. This war wasn't planned right, and it hasn't been executed right."

Irvine first called for Rumsfeld's resignation two years ago after the ghastly images from Abu Ghraib surfaced. Though much of the retired generals' criticism this month focused on the strategic quagmire in Iraq, he believes prisoner abuse remains at the heart of the battle against Rumsfeld.

"I sense a great deal of distress among senior military officers over what's happened with prisoner treatment," Irvine said. "I believe the abuse is playing a significant part in how these generals are feeling and why they're speaking out. There's an understanding that whatever we're doing at Guantánamo and elsewhere constitutes license for others to do to us when our soldiers are taken prisoner in the future. There's the realization that we've pretty much trashed the high ground along with the Geneva Conventions."

On April 14, Salon revealed that Rumsfeld was personally involved in directing the harsh interrogation of a prisoner at Guantánamo Bay, according to a sworn statement by an Army lieutenant general who investigated prisoner abuse at the U.S. base in Cuba.

Other critics note that the Pentagon has controlled all of the investigations to date into prisoner abuse.

"It's extremely difficult to believe that what happened at Guantánamo and Bagram and Abu Ghraib is all coincidental," said retired Brig. Gen. Jim Cullen, who served as the chief judge (IMA) of the U.S. Army Court of Criminal Appeals. "We need a much more extensive investigation into what went wrong and who at the top was responsible. With Rumsfeld continuing at the top that's not possible."

Cullen, who currently practices law in New York, has provided counsel in a lawsuit against Rumsfeld on behalf of prisoners abused in U.S. custody, and is one of 22 high-level retired military leaders who have urged the Bush administration to ban torture unequivocally.

"Personally, I don't believe the torture memos originated with Rumsfeld, but with Vice President Cheney and his top aides," Cullen said. "But Rumsfeld was quite willing to carry out those policies with enthusiasm. They were offensive to military culture -- a departure from the rule of law at the very core of military discipline. When you compromise that discipline and permit wrongdoing in the field, you have lost control of your forces, and you have compromised the mission."

The level of disapproval among active-duty commanders is more difficult to gauge. Direct criticism of one's superiors is a punishable offense under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. And under the current leadership, even dissenting views on strategy or policy can exact a heavy price.

"Everyone knows what happened to Eric Shinseki," said Irvine, referring to the Army general who resigned from the military in 2003 after clashing with Rumsfeld and his deputy Paul Wolfowitz over the number of troops needed for Iraq.

There is another reason active-duty commanders may be less likely to dissent these days, according to Irvine. "All of the people currently in positions at the two-, three- and four-star level have been extensively interviewed and handpicked by Rumsfeld. Some people would say there's nothing unusual about that, but I think there is." Historically, Irvine said, the top generals are selected by military promotion boards. "Yes, they are political positions, and the defense secretary has final say in the appointment. But in the past there has been more deference to the boards. I don't know that there has been this level of politicization of the generals' officer corps under any prior administration."

At least for now, the White House has made it clear that Rumsfeld will remain in his post. During an April 18 press conference in the White House Rose Garden, President Bush reminded the nation, "I'm the decider, and I decide what is best. And what's best is for Don Rumsfeld to remain as the secretary of defense."

His tenure has caused some unusual fallout.

"John Batiste is one very impressive commander," said Irvine. "It was particularly striking that he turned down a third star because he no longer wanted to work under Rumsfeld. There are not many guys in that position, and I have great respect for what he did."

Marine Lt. Gen. Greg Newbold, the Pentagon's former top operations officer, said recently that in the run-up to Iraq he raised his objections internally and then retired, in part out of opposition to the war -- and that he regretted the possibility that he hadn't done enough to stop it. His rebuke of Rumsfeld in Time magazine this month flowed in part from his view that "The cost of flawed leadership continues to be paid in blood."

Hutson, the former head judge advocate general of the Navy, said he is troubled by the status quo. "I have never seen Rumsfeld demonstrate self-awareness or the ability to admit mistakes," he said. "Unfortunately, I think that means we can expect things to go the same from here, with no end in sight."

"In a way, the response from the White House is understandable," said Irvine. "Iraq is President Bush's war. If the criticism of Rumsfeld is seen as valid, then responsibility for what has happened doesn't stop at Rumsfeld's desk. It goes across the Potomac."

Shares