Earlier this summer, I spent a week vacationing with some of my oldest and dearest friends, suffering most of the time from paranoia after one of them pronounced me "addicted to worrying" and another accused me of being relentlessly negative (I responded to her T-shirt, printed with the question "What Would Nature Do?" by asserting that nature is a whole lot more violent than Jesus). I resented being known so thoroughly and longed to be surrounded by intimacy lite: acquaintances and cocktail party banter buddies from whom I'm distant enough to ensure a conflict-free interaction, as opposed to friends who have compiled empirical evidence about my character defects over the years.

While I was busy questioning the benefits of intimacy, three sociologists from Duke and the University of Arizona were releasing a study called "Social Isolation in America." The researchers found that Americans have one-third as many close friends as they did 20 years ago, and nearly three times as many said they don't have a single confidante. This, by the way, is how close friends are defined in the study: people with whom one discusses important matters, though one person listed "getting a haircut" as an important matter. I count myself lucky to have more than the study's average number of friends and confidantes. In fact, I am a serial confessor and discuss important matters with anyone who'll listen; by the haircut standard, my postman Ronnie is a close friend. But like many other Americans these days, I find close friendships maddening and admit to the occasional onset of good old-fashioned misanthropy, a subscription to Sartre's observation that hell is other people.

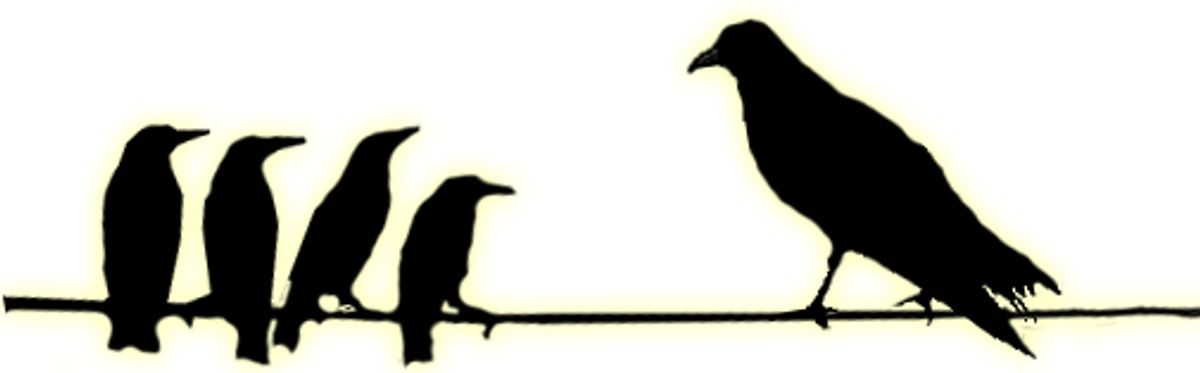

The study, a random sampling of 1,467 adults, sparked a short-lived whirlwind of media activity examining the crisis in American camaraderie, pointing the finger at sprawl and technology and work to explain it. But when I went out searching for the friendless, I found that overwhelmingly they blamed no one but themselves. They are what I'd call voluntarily lonely. Some people seemed almost proud to say they could call no one a friend, proud of the fortitude that loneliness requires. My dad once told me that friends are people you can do nothing with, but these days, people seem to prefer doing nothing by themselves. Are they choosing loneliness because friendship is so much work and real friends are hard to find and make and keep?

I didn't need to go far to find one of the voluntarily lonely, just down the block where my neighbor Stephen Cohen lives. Cohen had plenty of pals back in 2001, when he worked on Wall Street as a computer consultant, meaning he had disposable income and regular business hours and could spend evenings and weekends partying. "It was always about staying up late and being up on popular culture," he says. Then he got serious. Turned 30. Got his pilot's license. And he found as he outgrew his job that he outgrew his friends, too. "When I started to go to bed early, it was incompatible with that lifestyle." So he distanced himself from them, and, he says, "Eventually the phone just stopped ringing."

Cohen used to choose his friends, he says, "by if they listened to New Order or wore Doc Martens. From that quick assessment you knew you had things in common." Forming new friendships requires a certain chemistry, much as romantic relationships do, and the older we get, the more we have to approach friendships the same way, with friend dates and relationships and breakups. Now, Cohen says, "I'm really friendly, but I don't have any friends." By "friends," he means people he sees regularly, people who call to say hello. Cohen doesn't seem to mind the vacuum left by his old friends' departure. "I used my therapist as a surrogate," he says. "We stopped talking about my problems and I ended up just telling her about what I was doing that week."

Louise Hawkey, a research scientist in psychology at the University of Chicago, says certain people select what she calls existential loneliness. "They find it a purposeful, meaningful way of living out their lives," she says. Hawkey has been working on a study measuring the genetic predisposition to loneliness -- some people are more prone to it than others, but even for those, there may be a certain amount of self-deception involved in voluntary loneliness. "If people are choosing it, either they're perfectly able to live in those circumstances and aren't inclined to feel lonely," she says, "or they're really good at deceiving themselves that this is acceptable for them: The way to come to terms with a solitary life is to say, 'This is my choice. I like it like this.'"

A writer in Albany, N.Y., named Daniel Nester says when he relocated upstate from Brooklyn he chose to bring little of his old life with him beyond his wife and the contents of his apartment -- no one from his former circle of friends. "I'm currently not interviewing for new buddies. I've downsized my circle of friends to almost nil," he says. "I have one friend. I used to have 30." Petty grievances that were once small fissures grew to crevices as he prepared to leave, and instead of courting new friendships, he drew closer to his wife, filling the social absence with books. Nester would rather be friendless than in the companionship of what he calls "fool's gold" friends. "My faith in friendships is pretty low right now," Nester says, but his expectations are high. "It's like a blood bond: We confide in one another; we defend one another," he says -- anything less is not friendship at all.

Compared with Nester's single friend, Basya Grinhstein's strange and far-flung circle seems like a veritable in-crowd. Grinhstein, a 20-year-old from Houston, says she has three friends: Two live in other states and one is her 7-year-old brother, who has Down syndrome. "I paint by myself, I watch movies by myself, I go dancing by myself," she says. "With other people, I get irritated or feel uncomfortable. I'm not very trusting of other people." Yet she believes that her utter lack of interest in making friends draws people to her. "People always say, 'Can I have your number? Can I have a way to keep in touch with you?' and I'll say, no, I'm not really looking for that."

Every day on television, friends cross each other, betray each other, infuriate each other, and 22 minutes later, all fractures are repaired. In a media-saturated society that lionizes friendship, it's hard to believe that the voluntarily lonely aren't just playing hard to get. Our electronic culture and methods of keeping in touch -- cellphones, e-mail, instant messaging, text messaging -- are noted in the study as possible grounds for our increased isolation. For all their promise of keeping us connected, they often disconnect us, and the result is that we have more computer-to-computer than face-to-face time; my friends with BlackBerrys send the most perfunctory messages, and even the text "miss U" does not make me feel loved. One author of the study, Lynn Smith-Lovin, pointed out that a distant e-mail correspondent will be of little use when you need someone to pick up your kid at day care in a pinch. But Hawkey points out the Internet's social potential. "Some think that the Internet keeps people closer -- we'd lose touch with certain faraway friends and family if we didn't have e-mail."

For many, technology fulfills social needs, and old school pals become practically outdated. It's easy to see how blasting one's innermost secrets to the world at large on MySpace.com would preclude the need for confidantes. And if Doc Martens aren't enough to gel a friendship, one can search out others with a variety of aligned interests with whom to bond, or find a way for technology to replace the usual human interaction. My favorite waiter at the local diner told me that his wife spends a great deal of time on the Foo Fighters chat room, and that she witnesses entire relationships unfold electronically. "People are on there all day," he said.

Even if we've increased this virtual intimacy, an architecture of loneliness drives us apart. The researchers explain it this way: There has been "a shift away from ties formed in neighborhood and community contexts." In other words, those who suffer long commutes from the suburbs, work long hours, and come right back to the 3,000-square-foot McPalace, the three-car garage with a door leading directly into the home, never need to lay eyes on a neighbor. Even if we moved to suburbs envisioning utopia, suburban life is, in some form, voluntary loneliness.

The study finds that while Americans confide in fewer nonfamilial friends, they've drawn closer to their spouses. It's odd that this is presented as the disintegration of friendship instead of a testament to the strengthening bond of American marriage and faith in romance (though another study revealed that folks live longer surrounded not by family but friends). Six months ago, Cohen found the girl of his dreams and she became No. 1 confidante. "I don't have nearly as much to say to my therapist now that I talk Nicole's ear off."

As for my friends, I've been thinking about what we've been through together. One friend had abdominal surgery last year, and the group rallied by her bedside. Another has been struggling through chemotherapy, and we've had a series of celebrations for her, including a bye-bye boobie party before her double mastectomy. A friend flew out for my 30th birthday a few years ago, a miserable evening eating In-N-Out burgers and seeing a Robert Altman movie after some former friends canceled my birthday party. She saved me from, well, who knows what I would have done had she not been there? I may not see that friend every day. I don't discuss all my important matters with her -- or even my haircuts. We have dinner maybe just once a month, but she is my close friend. And, in fact, aren't friends in part there to call you out, alert you to your faults, and offer advice on how to correct them? Friends are there in case of emergency and, also, there to do nothing with. My friends are, it turns out, lie-down-in-traffic-for-you kinds of buddies -- I've had them all along, but never noticed.

Hard as I find it to navigate friendship, I'm lucky to have so many people I can call friends. But what about those who don't? What about those with only two confidantes, a couple of close friends? I don't see why that should be an indication that we're more socially isolated -- for some people, voluntary loneliness isn't so lonely after all. As Daniel Nester's mother always told him, "If you find one friend in your life, you're lucky."

Shares