"I got poetry in me."

That line, spoken by Warren Beatty's muttering, bearskin-wrapped frontiersman John McCabe in "McCabe & Mrs. Miller," is also the best possible summation of Robert Altman's career, not least for the way it suggests that poetry isn't a lofty, pretty thing plucked out of the air, but a hardy thing that grows wild inside us. Altman died Monday night. He was 81, and all of us who loved his movies -- the great ones and the minor entertainments alike -- knew we wouldn't have him around forever. But maybe partly because he never stopped working -- "A Prairie Home Companion" was released at the beginning of last summer, and he was already knuckling down to work on a fiction-film version of the 1997 documentary "Hands on a Hard Body" -- it's almost impossible to believe he's really gone. He revealed earlier this year that he'd received a new heart some 10 years ago, and the news was a comforting insurance policy to his audience. How many more movies could a new heart buy you? How many more lines of dialogue, each one chasing (or stepping on) the tail of the last, did Altman have time for? Greedily, we would take all we could get.

But even before the shock of Altman's death has worn off, let's take some time to marvel at how much we got, a body of work that few other modern filmmakers can match. Altman, along with Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma and Paul Mazursky, changed the landscape of filmmaking in the 1970s, but he might have just as easily squeaked into the generation before: By the time he'd made "M*A*S*H," in 1970, he'd already been directing documentaries and episodes of television series for nearly 20 years. He might have been a young maverick of '50s westerns or noir dramas. He was older, even, than the great Jean-Luc Godard, and yet certainly by the early '70s, when Godard's greatest work was already behind him, Altman seemed decades younger, as if he'd been saving up his youth to spend it at just the right time, just the right time for him.

And so when Altman really got cooking, in the last third of the 20th century, he had more than 50 years of movie culture to play with, and he did: He made westerns and noirs ("McCabe" and "The Long Goodbye"), gangster stories and war pictures ("Thieves Like Us" and "M*A*S*H"), and even, with "Nashville," his own version of the musical extravaganza. As critic Ray Sawhill wrote of him here in Salon, in 2000:

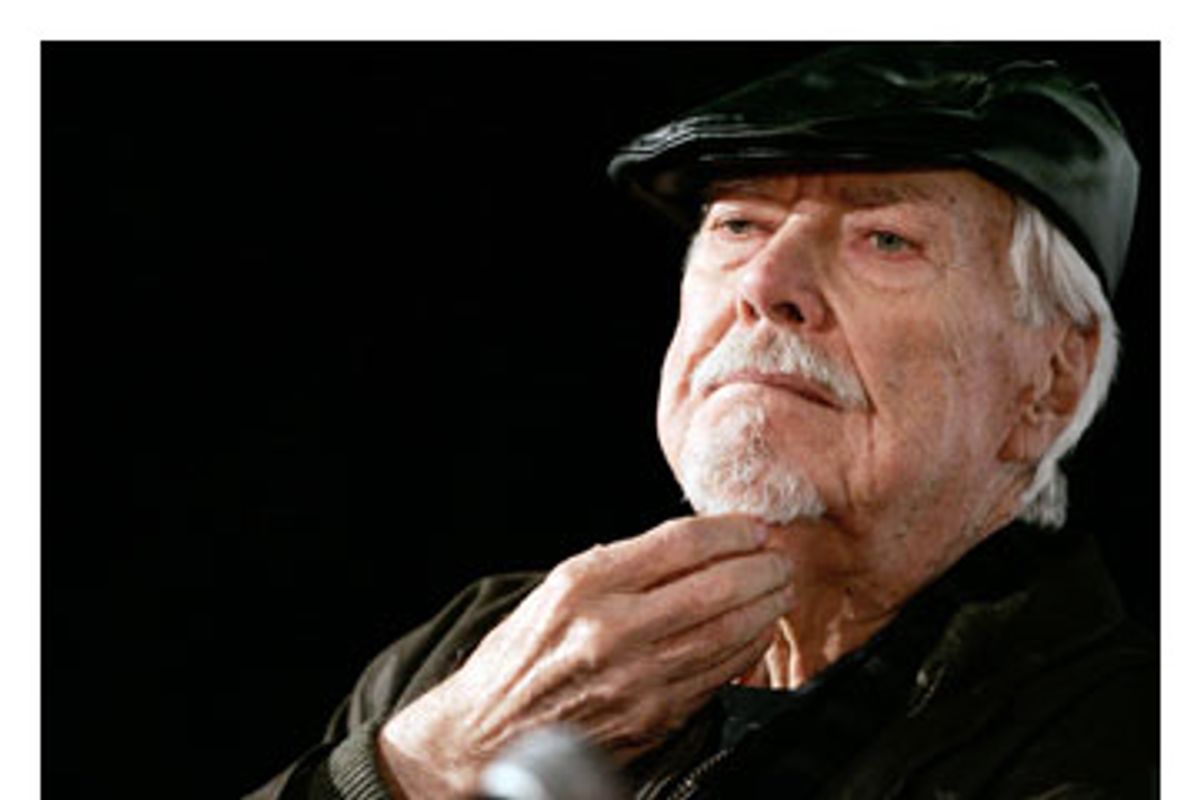

"He was a hip impresario, moving from detective movie to western to gangster movie, tweaking and twisting them, demanding more of these genres than they were used to providing. If Peckinpah was the barbaric, bitter celebrator of boozy grandeur, staking it all on the one great certain-to-lose gesture, Altman played the margins with a slipstream elegance, keeping a variety of bets in play at once. Tall and charismatic, with a goatee and long fine hands, he looked like something out of a Mark Twain story -- a frontier campaign manager, perhaps, or a riverboat gambler turned grandee."

During the course of Altman's career, there were times ("Prêt-à-Porter," "Kansas City") we wondered what he was nattering on about, times we weren't sure he had anything more to offer us. Other times, he gave us serviceable charmers like "The Company" and "Cookie's Fortune," pictures that may have been less than what we wanted from Altman, but which were still much more than lesser filmmakers could have given us on their best day.

Altman didn't hit the mark every time, but then, his movies were never about hitting marks: At their best and greatest, they were semi-improvisatorial flights of free-flowing precision -- in other words, they were moving contradictions, and you had to be flexible enough to move with them, to grab onto their weird poetry, which seemed to be forever ambling just out of our grasp. His most wondrous picture, "McCabe & Mrs. Miller," a dream unfolding in a snow globe, is the most perfect example of Altman's poetic gifts. But even in pictures whose names aren't generally rattled off on the "masterpiece" list, like "California Split," those gifts are undeniable. "California Split" is a story told in non sequiturs; its scenes don't quite seem to connect while you're watching them, and yet afterward, almost miraculously, they assemble into a kind of free-form music whose sound is hard to shake. (Bless New York's Film Forum for recently reviving "California Split." A colleague of mine who interviewed Altman just a few weeks ago told me that Altman was incredibly pleased that this "lost" little picture had received new life.)

Altman died of cancer, and apparently, he'd been working around his illness for the past year and a half, which makes his last great achievement -- "A Prairie Home Companion," a lovely end-of-an-era sonnet -- that much more remarkable. The fact that he did such terrific work so recently also makes his death harder to take: We haven't lost a relic, a golden-age great, but a great working filmmaker. But that's elating, too. Robert Altman went out in a blaze, looking forward to his next project. After we've spent some time mourning this man who took so much pleasure in his work, let's begin marveling at the way he passed that pleasure along to us so freely.

Shares