In 1968, through a fluke that remains a mystery, Chuck Hagel and his younger brother Tom became the only known American siblings to serve in the same infantry squad in the Vietnam War. The future Republican senator from Nebraska and anti-Iraq war maverick, then 21, fought side by side with his little brother in the steaming jungles of the Mekong Delta. They walked point together, they watched comrades get ripped in half by land mines, and they sent five Purple Hearts home to their mother. They also saved each other's lives.

Tom, two years younger than Chuck, saved his older brother first. Normally the Hagel brothers walked point, but one morning in 1968 they had rotated to the rear as their column of soldiers crept through the jungle. The soldier who took their place that day met instant death as he stepped on a huge land mine. Flying shrapnel ripped through the squad. It hit Tom's arm, but a bigger chunk lodged in Chuck's chest. Ignoring his own wound, Tom frantically wrapped compression bandages around Chuck's chest to stop the fountain of blood, praying his older brother would live long enough to make it out of the jungle.

A month later, their roles were reversed. Chuck saved Tom. During fierce combat, Chuck dragged an unconscious Tom out of a burning armored personnel carrier just before it blew up, turning his own face into a mass of bubbling blisters. Blood poured out of Tom's ears and now it was Chuck's turn to pray. Later, as he himself lay in a makeshift hospital close to death with severe burns, Chuck Hagel reflected on the horror of combat. "I vowed then to do what I could to stop wars," he told me years ago. "There is no glory in war."

When Chuck and Tom returned home to Nebraska, however, their similar experiences did not translate into similar politics. Their divide mirrored the deep ideological split of the nation. Tom thought Vietnam was a horrible waste. Chuck thought Vietnam was a noble cause gone wrong. Their disagreement over Vietnam led to shoving matches and fistfights.

In the years after Vietnam, Tom became a law professor and passionate liberal, Chuck a wealthy entrepreneur and senator and equally committed conservative. It took the brothers decades to reach a rapprochement about Vietnam, as Chuck gradually accepted some of Tom's arguments about the waste of American lives. When it came to the Iraq war, however, it took only a fraction of that time for their shared experiences to bring the brothers to similar conclusions, and to turn Chuck Hagel, as he proved again on April 26 with his vote for withdrawal, into the most visible Republican opponent of President Bush's Iraq policy.

Tom and Chuck Hagel were always opposites. In Roman Catholic school in Columbus, Neb., a town of 12,000 an hour and a half west of Omaha, Chuck managed to be both popular and the teacher's pet. He was a class leader, the homecoming king and a member of the football team. And he was always profoundly ambitious and interested in politics. Friend Dave Kudrow claims that when Hagel ran for student council, he had a campaign staff. "He made the prediction when in high school that he would someday be a senator." In college Hagel even signed a letter to an aunt "your nephew and United States senator."

Tom, on the other hand, was the rebel and class clown who did imitations of the nuns until he got kicked out of St. Bonaventure High. But he was so popular that after his expulsion, many of his classmates followed him out the door to public school.

But they both grew up poor. As their father bounced from small job to smaller job, the six-member Hagel clan moved from one little Nebraska town to another. One summer the four Hagel brothers, Chuck, Tom, Mike and Jim, even slept in a chicken dormer with chicks; another time they briefly lived in the furnace room of a hotel.

In that long ago other world, when the Hagels were living in Ainsworth, 7-year-old Chuck would awake in the dark, stuff wire cutters into his pockets and trudge to the nearby railroad station. Few passengers ever disembarked in a Sand Hills cattle town so remote that it proudly called itself "The Middle of Nowhere." Bundles of the Omaha Herald were tossed onto the platform from the still-moving train. In the winter, Chuck's hands would grow numb as he took off his mittens to cut the wire bundles, then deliver the paper around town with his sled.

Charles, the elder Hagel, had been a tail gunner in the Pacific during World War II and, on his return to Nebraska, was a hit at the Veterans of Foreign Wars halls. But professionally he was thwarted by his own father, the proprietor of a lumberyard chain. Charles moved from town to town working as a financial troubleshooter at the family stores until he quit. "His dad even told him once, when he had gotten a job someplace else, 'If you leave, I will disown you,'" recounted Charles' widow, Betty Hagel Breeding. Disillusioned by life, Charles doted on and transferred all his aspirations to his eldest son and namesake, Chuck. And he went on drinking binges that devastated the family.

Some years ago, sitting in a crimson silk high-back chair in his Senate office, Chuck Hagel told me about the tension that would build when his father did not show up for dinner. "Mom would have to get the car and go to the bar and get him." There was no money for a baby-sitter and so the whole family went, the three youngest sitting with wide eyes in the back seat. "I remember it as if it was yesterday," recalled Mike Hagel, the third-oldest brother. "Sitting there. Cold as hell. Waiting for Mom to come out of the bar with Dad. You try to block those things out. When kids in the neighborhood would say, 'Your dad's a drunk' -- that would hurt. But when he was sober he was the greatest guy with a great sense of humor."

With their mother holding up their father in the front seat, Chuck, who could barely see over the steering wheel, would get in the driver's seat. Said the senator quietly, "I'd have to drive the car home. At 11 years old."

When he was drunk, Charles took out his anger on his second-oldest son, Tom. "For some reason, the focus of his anger was me," Tom recalled. It didn't matter that Tom was the one who looked like Charles. He sought in vain the same approval that Chuck got without trying. "Oh, man, it was not good," Tom said. "Either something I did would trigger it, or I would be the outlet. I spent my life waiting for the shoe to drop. 'Is he going to come in, going to be sober, what's going to happen?' ... I could see it in my mother, right on the edge, very tense."

As he got older, it became Chuck's job to defend Tom. When he stepped into the fights, he too started taking blows from his dad.

"How it affects you," he continued, after a pause, "is that you're just hoping that tomorrow night is not one of those nights your dad goes on one of those. Because it's just a terrible thing. To see your brothers crying, to see your mother upset, it's a terrible thing that families go through."

Charles was out drinking on the last night of his life, Christmas Eve, 1962.

Tom, who was then 14, remembers that "the last contact I had with him was him beating me up. Jim [the youngest Hagel brother] and I were wrestling around, knocked over the Christmas tree, and we put it back. [Dad] chased me through the house. He was drunk. He said he was going to kill himself." Tom remembers a bottle of empty sleeping pills and a bottle of whiskey by his father's bed.

The senator deflects the inference. "He may have taken some sleeping pills, but the death certificate said heart attack," he said. Their father was only 39, but Hagel says he had health problems, by no means entirely alcohol related. "He'd had rheumatic fever when he was a child and couldn't play sports and had malaria in the South Pacific, which was a terrible strain on your heart, and then he had polio when he came back, wrecked three cars, which he walked away from, except one, when he broke his back."

Chuck's final memory of his father remains haunting. After the fight on Christmas Eve, his father came down to Chuck's basement bedroom. "And I didn't want to talk to him. I was so upset with him that he ruined Christmas. I told him to 'leave me alone.' And 'Go back upstairs.' That's the last thing I said to him."

Telling the story decades later brought no emotion to Hagel's face. "At 16 you're sailing into rough waters anyway ... My dad and I were starting to have some friction. When he drank, it made it worse."

The Hagels were living in Columbus, where Charles had been a salesman for a concrete company. Their home was a one-story frame bungalow with a basketball hoop above the garage door. Across the street lived Frank Murphy and his wife, known to one and all as Babe. Their house was a second home for the Hagel boys.

"The worst day was that Christmas morning," Babe recalled, "when Jim [Hagel] came over and said, 'There's something wrong with Dad. We can't wake him up.' And then Betty and all the kids came over here. Chuck and I went over, stripped the bed, cleaned up. [Chuck] stayed right with me."

All of the Hagel boys credit their mother, Betty, for the strength they showed after their father's death. "She was the glue that held us together," Mike said. "She was 39 and she had four sons to raise." But Chuck, always the responsible firstborn, grew up instantly when his mother told him, "You have to be the man of the house now.'"

Just over six years later, both Chuck and Tom had been to Vietnam and back. Chuck returned to Nebraska first. His facial wounds, which had become infected with jungle rot, were still raw. They would take a decade to heal fully. "I could never shave with a razor blade, just electric, because I would whack off new layers of skin coming onto my face." Meanwhile, he says, he "never had a moment's rest" until his younger brother made it home too. Before his tour was up, Tom got a second Bronze Star for valor when he took out a sniper. He also got a third Purple Heart, but his deeper wounds included bouts of post-traumatic stress disorder.

When her sons made it back from the war alive, their mother's relief was enormous. Then, as if playing out some horrific Greek tragedy, death came but a few miles from home. One night in 1969, Jim, the baby of the four Hagel brothers, then 16 and a star quarterback, hit a telephone pole with his car after a party. Tom had to identify the body. After all the dead he had seen in Vietnam, Tom took it very hard.

Now ready to begin their adult lives, it was apparent that Tom and Chuck had had very different reactions both to the horror they'd seen in Vietnam and to their hardscrabble upbringing. Tom went to law school and worked as a legal aide for the poor before becoming a law professor at the University of Dayton in Ohio.

Chuck was a conservative. After Vietnam, Chuck graduated from the University of Nebraska at Omaha and moved to Washington to work for Republican Rep. John McCollister of Nebraska from 1971 to 1977. But his combat experience had given him an empathy for the suffering of wounded soldiers. When Ronald Reagan won the presidency, Hagel became the deputy administrator for the Veterans Administration, inspired, as he put it, to work for Vietnam veterans "who were getting a raw deal." Soon he was embroiled in an effort to oust his boss, V.A. director Robert Nimmo, who had referred to Agent Orange as nothing more than a "little teenage acne." Hagel took the battle all the way to the White House. In 1982, after Hagel lost the fight, the Los Angeles Times editorialized that the wrong man had been fired.

That's when Hagel sold a 7-year-old Buick and two insurance bonds to gamble his net worth of $5,000 with two more solvent partners on a then-untested and unknown technology. Friends laughed in derision when he held a loafer to his ear, like the character with the shoe phone in the old TV spy spoof "Get Smart," and told them, "You just wait, in 10 years people will be walking around holding these little pieces up to their ears." Hagel's company, Vanguard International, became, for a time, the second-largest cellular phone operator in the world.

According to Tom, his own experience of doing without, of being on the outside looking in, inspired him to pull for the underdog. His brother's reaction to being on the outside, Tom says, was to try to get inside. Always ambitious, Chuck wanted access to wealth and power.

Having achieved wealth, Chuck made his bid for power after returning to Nebraska in 1992 to run an investment bank. He began to plan for his political future and for the realization of his childhood dream of being a senator. "He has," said a former partner, "a Rolodex the size of an oil drum." In 1996, after Democrat Jim Exon retired from the Senate, Hagel won a landslide victory in the Republican primary and an upset victory in the general election to succeed him.

After fewer than four years in the Senate, Hagel the war hero was on George W. Bush's short list of potential running mates in 2000. Once Bush was in office, Hagel signed on to his tax cuts and other agenda items. He had already racked up a nearly perfect score for his voting record from conservative watchdog groups. Tom was troubled by how little his brother, despite his own past, seemed interested in the plight of the less fortunate. "When I hear him talk about a legislative agenda, nowhere do I hear any concerns that would have an impact on poor or lower-middle-class people."

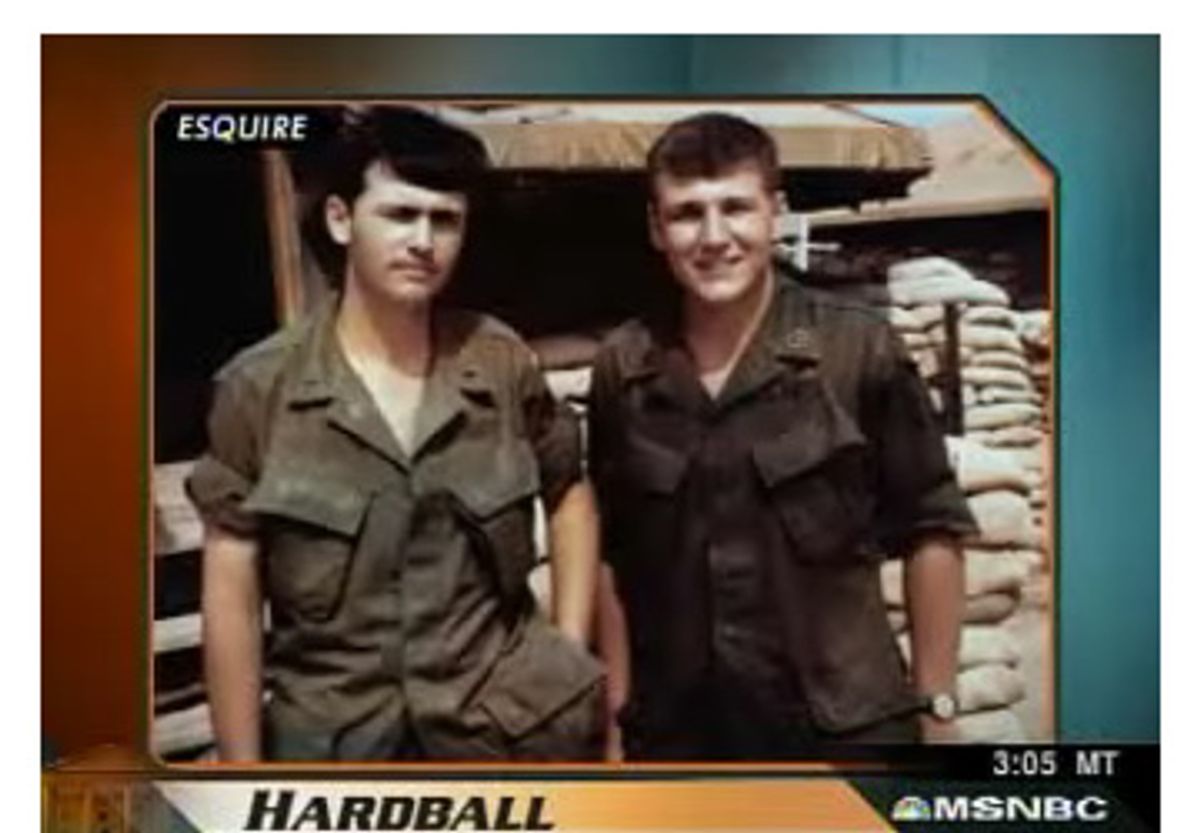

But on the subject of their experience in Vietnam, the brothers were finding common ground. Today on Chuck Hagel's Senate office wall there is a montage of three pictures of the two brothers -- one when they were young soldiers in fatigues and two taken in 1999 when they returned to Vietnam together for the first time.

The pictures were taken at a ceremony in Ho Chi Minh City, once known as Saigon, where the two were part of a delegation that attended the opening of the first American Consulate since the war. During the same trip, Tom and Chuck returned to the war zone, to the riverbank where Tom had saved Chuck. The trip was filmed for a documentary.

In the footage from the trip to the Mekong Delta, you can see in the brothers' faces a startled sense of being transported in time. Their van drives into the familiar green tangle of the humid jungle, and they roll the windows down. Into the vehicle waft the pungent smells of village coal fires and outdoor privies, and the suffocating heat, all unchanged.

Tom is overcome with emotion standing by the river where friends lay dying so many years ago, a river that flowed red with blood -- "like Campbell's tomato soup," he says. In one scene, Tom chokes up and has to walk away from the camera. "It was probably one of the most difficult emotional experiences of my life. Overwhelming. I was consciously, physically trying not to cry much of the time," he says.

Back in the United States, far from the scene, talking about the trip and the making of the documentary, Tom's face went ashen recounting how a friend died. "Someone had pulled him out and he was leaning up against a tree with just ..." He motioned to the knee area where the soldier's legs had been blown off. He choked back tears, and there was a long pause. "Whew," he said, clearing his throat.

The senator, meanwhile, said that the return to the jungle "was much harder than I thought it would be." Yet during the trip, at least on the surface and on camera, he remained characteristically cool. In general, Tom said, even during the period when he and his brother were having fistfights about the politics of the war, Chuck has kept the same equilibrium when he talks about his experiences. "I have never, ever," Tom said, "seen Chuck express himself about Vietnam emotionally at all."

What is different now, Tom said, is his brother's feelings about the meaning of the war: There "has been a sea change for Chuck, and that is about the core of the conflict between us, the Vietnam War, whether it was justified and all of that. He has now come around 180 degrees in his thinking. I never changed my feelings."

Hagel told Tom the same thing he has told others. What finally opened his eyes and turned him around was listening, in recent years, to tapes of Lyndon Johnson and his advisors, tapes that were made two years before the teenage Hagel brothers went to Vietnam. The tapes, Tom said, "acknowledged that they weren't going to win the war but kept dragging it on to get the best deal. They sent people to a slaughter just to wait it out to get the best political deal."

Tom's sense of having been betrayed, like that of many veterans, was so intense and immediate that, he said, "it used to drive me nuts that Chuck couldn't see it. It seemed to me so clear that we were used."

Now, Tom said, without bitterness, "we have just finally laid it to rest."

In 2007, the brothers are again on the same side about a war. Once again, they got there from very different places. Tom opposed the war in Iraq from the start. As he listened to the 2002 congressional debates about granting the president the authority to go to war, he cheered as his brother the senator expressed serious reservations -- "imposing democracy through force is a roll of the dice." Then Chuck voted with the majority. Said Tom, "He just couldn't pull the trigger."

Today, Chuck Hagel, who confirms that he and his brother have "talked about [Iraq] a lot of times," emphasizes that he had "very significant concerns early on." He also takes care to note that Democratic presidential hopefuls Hillary Clinton, John Edwards and Joe Biden, like him, voted to authorize the president to go to war. He explains his vote this way: "I believed the president and others who said they would exhaust all diplomatic efforts. Which they did not. They told us they would and they did not."

He turned against the war as it became a morass. He saw the parallels with the earlier war he'd been slow to condemn, and soured on it far more quickly. When President Bush announced plans for the surge, Hagel called it the "most dangerous foreign policy blunder in this country since Vietnam." Then in March, Hagel clinched a win for the Democrats by voting with them for a war-funding bill that mandated withdrawal by 2008. On April 26, when the Senate passed the final version of the bill, Hagel again sided with the victorious Democrats. He was one of two Republicans to cross the aisle in a 51-46 vote.

President Bush has vowed to veto the bill, calling withdrawal the prelude to a bloodbath. Hagel is furious at the president for trying to shift blame to Congress and for equating support for withdrawal with not supporting the troops. "I am solidly behind where we are in the Senate, how I voted," Hagel said. "It is wrong to escalate our military involvement in Iraq. It will end in disaster. You bog down and you bog down and you can't get out."

The day after my most recent of many interviews with him, Hagel left Washington for his fifth visit to Iraq. While in Iraq, he took a swipe at surge supporter John McCain during a press conference. "We didn't go shopping," said Hagel, archly, referring to McCain's infamous stroll through an open-air Baghdad market while protected by massive firepower. On his return from Iraq, Hagel gave his younger brother Mike a grim assessment. "Every time I go over," he said, "it gets worse. It is so bad now it is pathetic."

In his office, prior to the trip, he was more measured. "An additional 50,000 troops is not going to turn that around. We cannot stay as an occupying force, which is essentially what we are. It is a violent sectarian conflict fully complicated by an intrasectarian conflict. That's a civil war. To put American troops in the middle of that is wrong, and to further escalate our military involvement is wrong."

To that, brother Tom would say amen.

Shares