Election Night 2002 was a gloomy watch for Democrats. Their party, led by a pair of innocuous Midwestern Main Streeters, Richard Gephardt and Thomas Daschle, lost control of the Senate and lost seats in the House, sinking to its lowest ebb since the Roaring '20s. Smug right-wing pundits predicted the Democrats were on their way to joining the Whigs in the ashcan of American political parties.

It was a different story in Illinois. The Democrats won everything. They took the governorship for the first time in 30 years. They captured the state Senate. This despite running a ticket made up of ward bosses' children and in-laws. I remember sitting on my couch in Chicago and thinking, "If the Democrats want to turn it around, they need to take some lessons from the machine around here. Chicago Democrats have no scruples. They treat political offices as feudal inheritances. They shake down contributors like a corrupt pope selling indulgences. They're sleazy, they're arrogant but they WIN."

That night, on the northwest side, Rahm Emanuel was elected to Congress. A former Clinton whiz kid who'd gotten his start as a fundraiser for Mayor Richard M. Daley, Emanuel was connected -- in the three years after leaving the White House (where he'd helped push through NAFTA), he earned $16 million putting together Wall Street mergers. He was also zealously partisan. He had once owned a consulting business devoted to finding skeletons in Republican closets. At a Clinton victory dinner in Little Rock in 1992, Emanuel celebrated by reciting a hoped-for necrology of Democrats who had "fucked" the president-elect. After every name, he stabbed a steak knife into a table and screamed, "Dead man!"

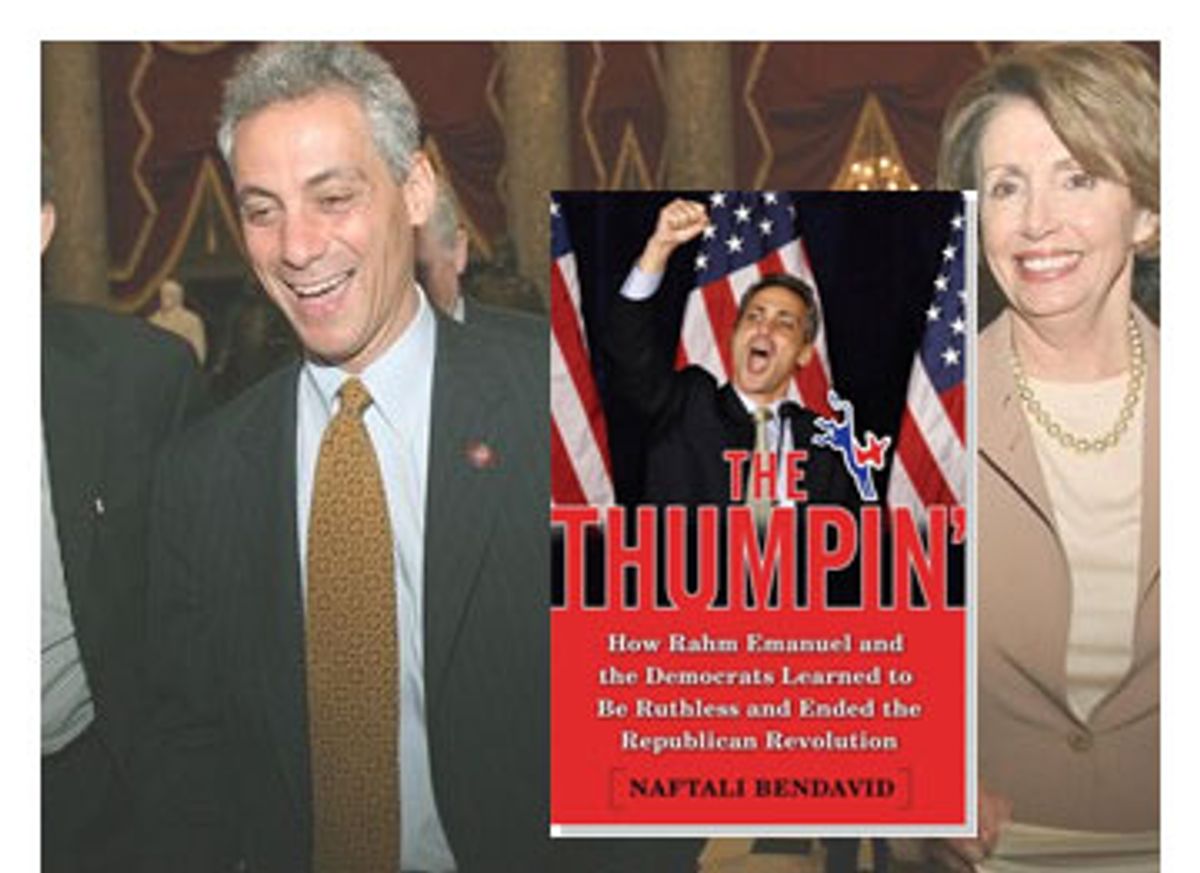

It's hard to imagine Tom Daschle carrying on like that. His strongest epithet was "I'm very disappointed." As it turned out, Emanuel was just the kind of shameless asshole the Democrats needed to win back power. As head of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, he raised millions of dollars by browbeating donors and candidates with cellphone calls that invariably ended, "Fuck you. I love you." Emanuel was so effective that not only did his party win back Congress, he was able to get a Chicago Tribune reporter to write a book giving him most of the credit. Naftali Bendavid, the Tribune's deputy Washington bureau chief, was given "insider access" to Emanuel's operation, expecting to write a newspaper article. When the Democrats triumphed, he expanded it into "The Thumpin': How Rahm Emanuel and the Democrats Learned to Be Ruthless and Ended the Republican Revolution." It's a 218-page celebration of Rahm, as interesting for its look at how he has built his political persona as how he managed the Democrats' campaign. Emanuel comes off as one of the most colorful, driven and profane Washington characters since Lyndon Johnson. "The Jewish LBJ," political scientist Larry Sabato calls him, not only for his ambition but also for his reputation as an amoral political animal focused only on power.

Freed from the constraints of his stuffy newspaper, Bendavid is able to ratchet up the parental guidance rating from G to R, which is essential to any well-rounded profile of Emanuel. As they said about Buddy Hackett in Vegas, Emanuel works blue. "Fuck" is one of the most versatile words in English, but he seems to have discovered new grammatical and linguistic uses for it. Washington is "Fucknutsville." A Republican congressman is a "knucklefuck." As with his liberal politics, he seems to have inherited his gift for invective from his mother, who is quoted as playfully calling him a "little shithead." The Emanuels -- who hail from the upper-middle-class suburb of Wilmette -- are an intense, competitive family. Emanuel's father and brother are surgeons, another brother is a Hollywood agent who inspired the Ari Gold character on "Entourage." Too tightly wound to stop at politics, Emanuel also races in triathlons.

In early 2005, Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi asked Emanuel to head the party's congressional campaign, attracted by his fundraising skills and his reputation as "tireless, aggressive and pushy." Emanuel's first job was recruiting candidates. Believing that Congress would be won or lost in a handful of swing districts, he sought out moderate and conservative Democrats. It was more important that they shared their hometown's values than the values of the national party. In the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, he found Heath Shuler, a former Washington Redskins quarterback who cut ads about his devotion to family, church and prayer. In southern Indiana, it was Brad Ellsworth, an antiabortion, anti-gun control sheriff.

Maybe because Emanuel is a wealthy suburban kid who studied ballet at Sarah Lawrence College, he was sensitive to the Democrats' image as an effeminate party. "Emanuel ... delighted in finding candidates who fit the manly mold -- military veterans, police officers, pilots," Bendavid writes. Many liberal bloggers, meanwhile, saw Emanuel as a triangulating sellout, an unprincipled hack making a reflexive, outdated and misguided rush for the center. They were committed to winning too, but they also wanted to draw a sharp distinction between Democrats and Republicans. Livid at Emanuel's statement that the party would take a position on Iraq "at the right time," they "lashed out at the DCCC for representing a muddle-headed centrism that would never rescue the Democrats or reignite the sweeping populism the country badly needed," Bendavid writes.

Blogger David Sirota spoke for an Internet wing that felt Emanuel "seemed to think that having no ideology, no convictions, is a winning formula ... Even if you do win under that scenario ... you have created an extremely tenuous majority." (Even after the election, the Nation's Web site insisted that many Democrats had won "despite the Illinois congressman," and the party would have captured more seats with an antiwar, anti-free trade platform.)

Bendavid may write for the Tribune, but he seems more familiar with Washington campaign headquarters than Chicago ward offices. If he'd worked a local beat, he could have provided a little more insight into how Emanuel's Chicago background, and not necessarily his years as a Clintonian triangulator, had shaped his politics. In Illinois, politics is not about ideology. Politics is about winning elections so you can give jobs to your family and contracts to your friends. Practical to the core, Illinoisans hate extremists who want to gum up the government with arguments over immigration or the Ten Commandments. The religious right is regularly trounced in Republican primaries, and the activist left is confined to a few neighborhoods of shabby three-flats on the Chicago lakefront. The state's last Republican governor, George Ryan, won by running to the left of his Democratic opponent on gay rights and abortion. In an environment like that, you learn to look for the center.

The netroots also mistrusted Emanuel because of his clash with Democratic National Committee chairman Howard Dean, a lefty-blog favorite. Dean was spending the DNC's cash on his "50-state strategy" to build up the party in Republican enclaves like Wyoming and Idaho. It was a long-term plan that even he admitted might not come to fruition for several presidential elections (though after the election bloggers would point to a blue wave in state legislatures as an early sign of success). As Emanuel saw it, he had to win now, and that meant pouring money into districts where Democrats were competitive.

Emanuel had witnessed this struggle in Illinois, too: it was the party regulars versus the goo-goos. Emanuel, the Daley protégé, is a regular who believes money and a disciplined organization win elections. He seemed to see Dean as a goo-goo, a good-government reformer with a base of liberal idealists who are more educated and individualistic than your average Democratic machine foot soldier, but less reliable when you need someone to hand out palm cards on Election Day. The machine has been paving over goo-goos since the 19th century. As a beery alderman once put it, "Chicago ain't ready for reform."

When Emanuel and Sen. Charles Schumer of New York met with Dean to ask him to shift money to congressional races, Emanuel mocked the former Vermont governor as a political lightweight from a tiny, rural, homogenous state. "No disrespect, but some of us are arrogant enough, we come from Chicago, we think we know what it means to knock on a door," Bendavid quotes Emanuel as telling Dean. Emanuel "slammed his hand on the table," then continued his tirade: "Look, Chuck comes from Brooklyn. I come from Chicago. It ain't Burlington, Vermont. Now, we understand that Burlington knows a lot about grassroots politics and we know nothing. I know your field plan -- it doesn't exist. I've gone around the country with these races. I've seen your people. There's no plan, Howard."

According to Bendavid, Emanuel left the room vowing not to be seen with Dean if the Democrats lost on Election Day. When Dean eventually offered $20,000 a race, Emanuel told him to fuck off. (Not literally -- although it's plausible.) Eventually, Dean ponied up a $12 million nationwide get-out-the-vote drive.

In other respects, though, Emanuel did have a 50-state strategy. He wanted to nationalize the election in the same way the Republicans had in 1994, with their Contract with America. Emanuel's message: "The Republicans were entrenched, tired, incompetent, corrupt." When his opponents did everything they could to validate his charge, Emanuel looked as much like history's darling as its maker. Bendavid acknowledges that his subject "was not responsible for the major factors behind the Republican rout. He had not affected the course of the Iraq war, persuaded the Republicans to botch the Hurricane Katrina recovery, or created the GOP corruption scandals. Emanuel's job had been to position the Democrats so that if a political tidal wave did emerge, the party would reap the benefit."

On the other hand, no politician can be faulted for being in the right place at the right time. When Emanuel took the job, he never expected to win, but he knew a president's party usually loses seats in the sixth year of his term, and he figured if he could pick up 10 or 12, he'd be rewarded with a leadership position, a step toward his goal of becoming speaker of the House. (He is now chairman of the Democratic Caucus, the fourth-ranking post in the House.) If he makes it, C-SPAN may have to institute a seven-second delay. On Election Night, 10 minutes after CNN called the House for the Democrats, Emanuel climbed up on a table in DCCC headquarters and addressed his cheering, victory-starved staff, celebrating the party's biggest win since 1992. He wanted to wrap up the campaign with a message for the Republicans.

"Since my kids are gone, I can say it," he shouted. "They can go fuck themselves!"

Shares