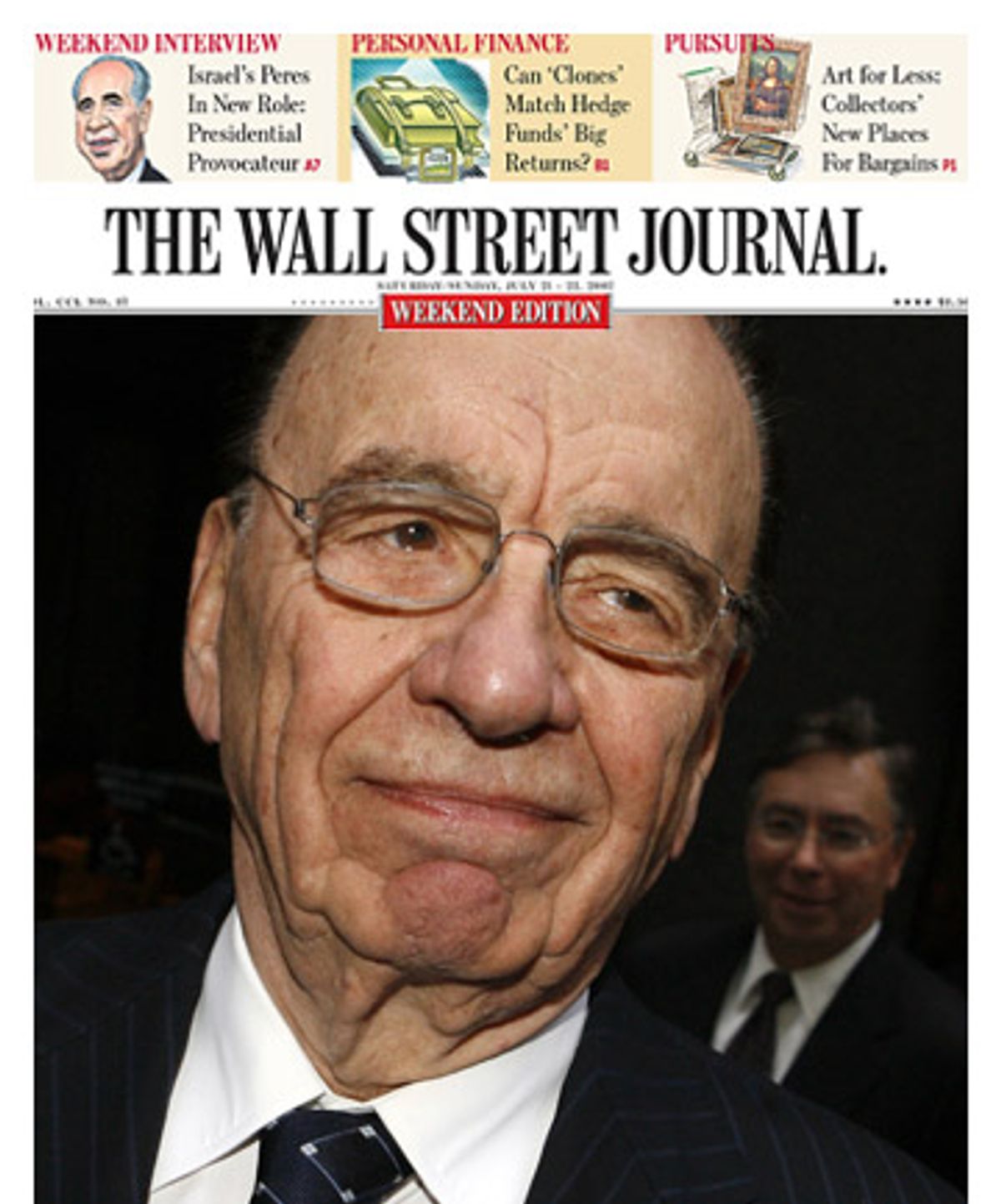

The coming week may determine whether the nation's foremost provider of business news, the Wall Street Journal, remains independent or is acquired by Rupert Murdoch's News Corp. Murdoch's $60-per-share bid for the Journal's parent, Dow Jones & Co., shows that the company has long-term value. The question now is this: Which family will reap that value: the Murdochs or the Bancrofts?

Of course, there's more at stake than the personal fortunes of the Murdoch family and the Bancroft family, which for a century has controlled Dow Jones. I'm a newscaster for the Wall Street Journal Radio Network and the president of the union local that represents 2,000 Dow Jones employees, including its rank-and-file journalists throughout North America. I believe our members' interests are best served by adherence to the principle of editorial independence within a company whose only mission is reporting the news. As journalists and union members we see no upside in reducing Dow Jones to a tiny appendage of a global conglomerate with financial, political and regulatory interests alien to what we do.

But this is not just a sentimental attachment to fearless and independent journalism. No one looks at business with clearer eyes than the reporters and editors at Dow Jones. Because many of us are shareholders too, we would even make some quick money off the sale. Yet we think the takeover is bad business. Not just bad for journalism, bad for readers, bad for advertisers, but bad for the long-term interest of shareholders, most of all the Bancrofts. Here's why:

Buy low, sell high: That's the most basic advice for any investor. It means sensing the most opportune time to initiate a transaction. Murdoch has built his conglomerate in part by his knack for timing. We should step back and consider why his bid came at this time.

News media shares are underpriced. It's a time of transition from print-based distribution to digital. The way that evolution unfolds remains uncertain, and uncertainty depresses value. But while the economic model is changing, the innate value of Dow Jones' product -- news that people can rely on when making their most important decisions as investors and citizens -- is unchallenged. Dow Jones has adapted to meet every other technological change over its 125-year history, from teletypes to satellites. The Internet isn't the first structural challenge our business has faced, and long-term investors should know this.

Dow Jones, however, has new, untested people in its top positions. Chief executive Rich Zannino is a former garment industry executive. Board chairman Peter McPherson is a former university president. The Bancroft family trustee, Michael Elefante, is an estates lawyer. None can match Murdoch's savvy in his chosen arena -- and each would profit handsomely if the deal goes through. It's easy to see why Dow Jones' outclassed management team, which couldn't even persuade Murdoch to raise his bid by a single penny, would choose certain short-term gain over an unwritten future.

Sell the cow? Or just the milk? Murdoch says he wants to exploit the credibility of the Dow Jones brand name for a proposed cable business-news channel. He calculates that buying the whole company is the most economical way to purchase that credibility. But that doesn't mean it's the most profitable way for the Bancrofts to dispose of it.

News organizations can transmit their reporting through different arrangements, including syndication, licensing and content sharing. If Murdoch wants Dow Jones' content, that content can be supplied through methods that don't mean the end of Dow Jones as an independent entity. For instance, Murdoch could offer Dow Jones a half interest in a new business-news channel in exchange for access to its reporting. That would preserve the independence and reputation of Dow Jones, bring its news-gathering expertise to viewers -- and create a long-term income stream for the Bancrofts. It's the difference between selling your cow for a one-time payment and selling her milk every day. Murdoch would rather buy the cow -- but if you're the farmer, why should you sell?

Be swallowed or die? The deal makers -- including Dow Jones board members and executives who stand to reap millions from the sale -- tell the Bancrofts that the economy can no longer support a relatively small, independent, serious news-gathering company. They claim that traditional reporting must be subsidized by entertainment ventures ranging from "American Idol" to the famous Page 3 girls of the U.K.'s Sun newspaper. But that model isn't business -- it's charity. It's also dead wrong.

Prior to the appearance of Murdoch on the scene, we at Dow Jones had begun an aggressive process to build new platforms, opportunities and investments to strengthen the company. Zannino himself, in an internal memorandum issued after the Dow Jones board endorsed the sale, acknowledged that this plan was "beginning to pay meaningful dividends and we have a very bright future as an independent company should the News Corp. bid not come to pass." The next day, Dow Jones reported that quarterly earnings had risen 16.2 percent.

Many of the world's most successful companies have staked their fortunes on independence instead of so-called synergy. In another industry struggling with change, car giant Daimler is trying to rescue itself from an ill-fated acquisition of Chrysler. Meanwhile, rival BMW has been promoting its independence. "No, we will not sell out to a parent company that will meddle in our affairs and ask us to subject our cars to mass market vanilla-ism," the automaker's advertising says. The fact is that even within a single industry, companies succeed because of management leadership, focus and execution of a sound strategy, not just size.

Dow Jones wasn't for sale when Murdoch appeared, and for good reason. The process of transformation that we had begun, creating new value while perpetuating our original mission, was working. Selling out now will only short-circuit that process -- and guarantee that the Murdochs, rather than the Bancrofts, reap its rewards.

Those who know the company best agree. Dieter von Holtzbrinck, former head of the German publishing giant, resigned from the Dow Jones board on July 19 to protest its plan to sell out. Board members Christopher Bancroft and Leslie Hill, both Bancroft family heirs, are acting on their own long-term vision by seeking creative ways to reinvigorate the company, with the right management, the right investments and the right strategy.

In promoting the Wall Street Journal and its other publications, Dow Jones tells readers they can rely on the expertise of reporters and editors who know business better than anybody. So when we say the takeover of Dow Jones is a bum deal, one being rushed to signature for all the wrong reasons, we hope our most faithful readers, the Bancrofts, will listen.

Shares