Forty years and four days ago, Hillary Rodham stormed into a friend's dorm room at Wellesley College and slammed her book bag against a wall.

"I can't stand it anymore!" she screamed, in tears. "I can't take it!"

It was April 4, 1968, and Hillary had just heard the news of Martin Luther King's assassination. The entire nation was grieving that day, but Hillary's anguish was especially palpable, because King himself had started her on her path to political awareness, when she'd shaken his hand after a sermon in Chicago.

The next day, Hillary marched in Boston's Post Office Square, returning to campus wearing a black armband. At a student body meeting at Houghton Memorial Chapel, she boldly spoke in favor of a two-day strike, nearly shouting down a professor who suggested that students give up their weekends instead.

"I'll give up my date Saturday night, Mr. Goldman, but I don't think that's the point," she said. "Individual consciences are fine, but individual consciences have to be made manifest."

Just four years earlier, Hillary had been a suburban Goldwater Girl, wearing a 10-gallon hat adorned with the candidate's catchphrase -- AuH2O -- and devouring "The Conscience of a Conservative," the Arizona senator's campaign biography, the way some young people take to the me-first bromides of Ayn Rand. The story of her conversion from high school Republican to Seven Sisters campus liberal is the story of how the Democratic Party was gentrified in the 1960s, its lunch-bucket rank and file making way for college-educated professionals consumed with issues of civil rights and unjust wars. And its ironic coda is that Hillary Clinton, once one of the activist newcomers, now depends for her electoral survival on reviving the party's old blue-collar base.

Hillary's Republicanism was a family heirloom. Her father lost a race for alderman in Chicago before fleeing to the suburb of Park Ridge, and had hated the city's Democratic machine ever since. In 1960, Hugh Rodham supported Richard M. Nixon for president. His 13-year-old daughter went along enthusiastically. The day after John F. Kennedy won the election, Hillary's social studies teacher came to class bearing bruises, inflicted, he claimed, by Democratic goons who didn't like the way he was questioning poll watchers in his Chicago precinct.

Outraged, Hillary and her best friend, Betsy Johnson, sneaked downtown to join a group of Republicans investigating the stolen election. The two girls were dropped off on the South Side, where they canvassed apartment houses and taverns, looking for evidence of ghost voters, which they never found.

"We had clipboards. and we had to register whether people lived there," said Johnson, now Betsy Ebeling, in an interview. "[What we did] was kind of jaw-dropping."

By the time she reached high school, Hillary was being exposed to the influences that would shape her later liberalism. Among them was Don Jones, the youth pastor at First Methodist Church. Fresh out of seminary, Jones was a pretty hip guy for early '60s suburbia: He drove a red Chevy Impala and turned his pupils on to Bob Dylan, French cinema and civil rights. In 1962, he took a group of young people to downtown Chicago, where they listened to Martin Luther King Jr. deliver a sermon accusing people who ignore social change of "sleeping through a revolution."

Jones found the topic "poignant and apt" for the teenagers, he said recently. Civil rights was "the biggest social revolution we've had in this country," but it was almost never discussed in Park Ridge. After the sermon, Jones took his students backstage and introduced them to King. Eventually, the young pastor was nudged out of First Methodist for his progressivism. But he and Hillary began a correspondence, and more than 20 years later, when Jones was teaching at Rice University in Houston, Hillary invited him to the Arkansas governor's mansion in Little Rock.

"Hillary began to reminisce," Jones said. "One of the very first things she said was, 'I'll never forget you arranging all of us to go backstage to personally meet Martin Luther King. At the time, I didn't realize how important that event would become for me.'"

When Hillary went off to Wellesley College, she took Park Ridge's politics with her. As a freshman, she was elected president of the school's Young Republicans chapter. But Hillary was also a proponent of King's civil rights movement, recalled her political science professor, Alan Schechter. And as an ambitious young woman hoping for a legal career, she was strongly in favor of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination based on gender. Signed by President Lyndon Johnson, it "was seen by the students as the Democratic Party pushing for women's rights, and that was an issue that resonated with them," Schechter said.

"I guess you can say I am becoming more liberal," she wrote to Don Jones, "but what does 'more' mean when you start from nothing?"

Kevin O'Keefe, now a Chicago lawyer, met Hillary in 1966, on a double date with a University of Illinois frat brother. Hillary still thought of herself as a Republican, and when the conversation turned to her favorite subject -- politics -- "she made some kind of remark about Daley and Democrats in Chicago, and I bet it was a suburban Republican comment," O'Keefe said in an interview.

Her Republican identity couldn't withstand the era's events, especially the Vietnam War. In the winter of 1968, Hillary spent weekends in New Hampshire working on the presidential campaign of Minnesota's dovish Sen. Eugene McCarthy.

When King was assassinated, Hillary was student body president at Wellesley. Despite her anger, and her harsh speech at the chapel, she turned out to be a moderating influence on campus. Hillary and O'Keefe talked often of the possibility of revolution that year, but both agreed they would never take part. In a democracy, you had to work within the system. The week of King's death, Hillary was true to that philosophy. There was talk of a hunger strike, but Hillary helped work out a more practical solution: pressuring the administration to recruit black faculty and students.

After Sen. Robert F. Kennedy was shot to death, in June, Hillary spent hours on the phone with O'Keefe, sharing her grief.

"I think that by certainly '68, she was thinking more like a Democrat than a Republican," O'Keefe averred. "She started to see a world beyond Park Ridge. It was a management town. There was no poverty. They didn't see strikes or lockouts."

Nonetheless, when Hillary applied for the Wellesley Internship Program in Washington, Schechter assigned her to the House Republican Conference, thinking she would fit well with Wisconsin Rep. Melvin Laird, its middle-of-the road leader. Hillary, who had resigned from the Young Republicans, "objected to no avail," she wrote in her memoir, "Living History."

As an intern, she wrote Laird's "Fight Now, Pay Later" speech, criticizing Defense Secretary Robert McNamara for hiding the cost of the Vietnam War.

"She was very much opposed to the war," Laird said in an interview. "She thought it was a mistake that we were there."

Hillary was also assertive enough to debate Laird -- who became Richard Nixon's first secretary of defense the following year -- on Vietnam. So he wasn't surprised when she became a Democrat.

"Most of those young kids in college, you find them in between," Laird said. "I had quite a few interns. I always found that a lot of them were feeling their way. I had some others that went that way, too."

That summer, Hillary accompanied House Republicans to the party convention in Miami Beach, where she staffed a Rockefeller for President suite. She was appalled by the nomination of her teenage political crush Richard Nixon, who was hustling the votes of Southern conservatives.

"Nixon cemented the ascendance of a conservative over a moderate ideology within the Republican Party," she wrote in "Living History." "I sometimes think that I didn't leave the Republican Party as much as it left me."

Later that month, back home in Park Ridge, Hillary saw news of the riots at the Democratic National Convention. Telling their parents they were going to a movie, she and Betsy Ebeling drove down to Grant Park and walked through clouds of tear gas, past battles between cops and antiwar demonstrators. At one point, they ran into a high school classmate who was providing first aid to the protestors.

The Vietnam War, Ebeling said, "was a huge dividing point for all of us. I think we were all really questioning it. All of that, McCarthy and all of that stuff, had come to a point where we decided we couldn't support an organization that was for the war."

When Hillary returned to Wellesley, she told Schechter she wanted to write her senior thesis on Saul Alinsky, the radical Chicago community organizer she had met during a previous summer break. That's when the professor knew she'd passed a watershed -- much as the rest of the country did that year.

"What that meant was that she was vitally interested in the problems of poor people," he said. "And Republicans are traditionally not interested in the problems of poor people. By that September, she had made up her mind."

In the late '60s, Hillary made the same ideological journey as so many well-educated suburban children who would become the Democratic Party's brain trust: civil rights lawyers, consumer advocates, college professors, political consultants, nonprofit executives and newspaper editors. After 1968, they wrested the party from Southern courthouse gangs and big-city Northern machines. By 1972, Mayor Daley -- a man Hillary was raised to despise -- couldn't even get a seat at the Democratic Convention.

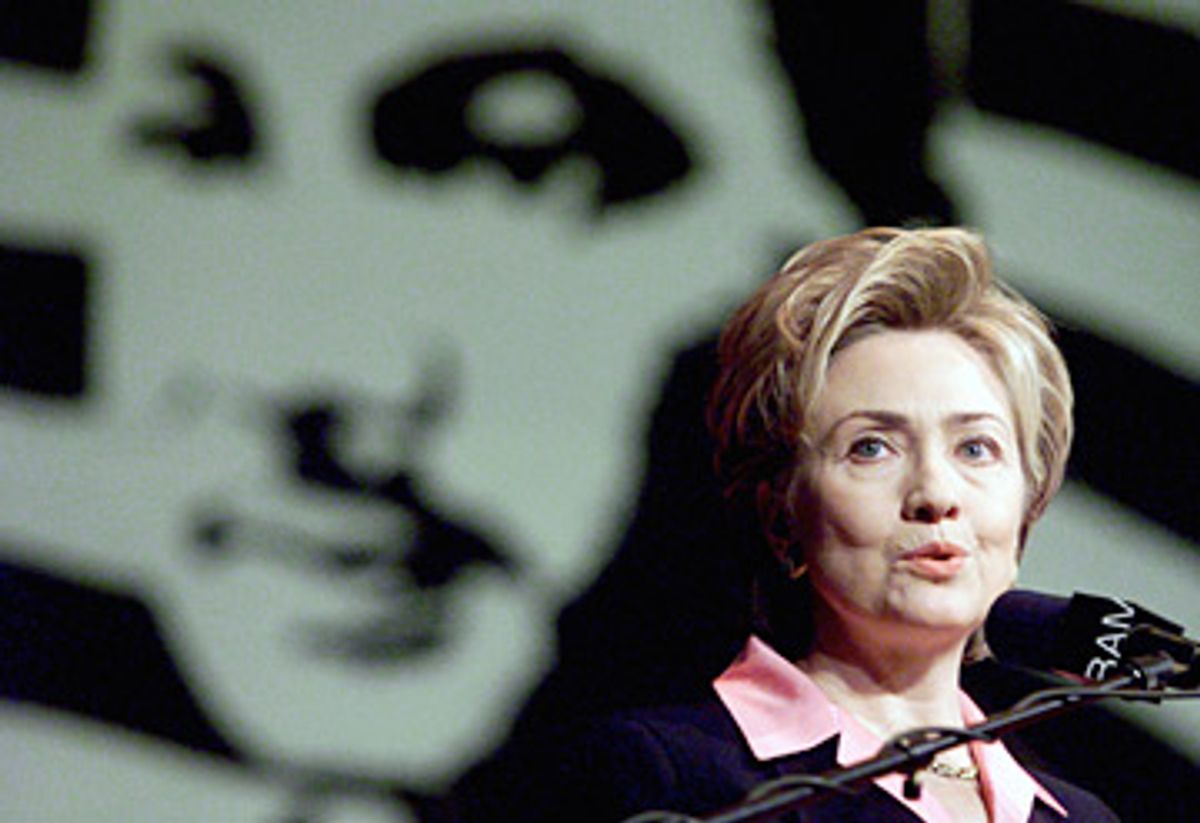

Nearly 40 years later, the roles are reversed. It's Clinton who's seen by many activists and college kids as a hawkish, racially insensitive backroom pol. She trails a candidate who, rather than writing about Saul Alinsky, put Alinsky's ideals into practice as a community organizer. She has managed to alienate liberals and African-Americans by contending that Lyndon Johnson, not Martin Luther King, made civil rights a reality -- slighting her youthful idol for the old-school Democrat who escalated the Vietnam War. Having reinvented herself once as a '60s liberal, her hopes for the nomination now hinge on selling herself as a blue-collar heroine. Let Obama win the eggheads; she wants to win the Roseanne vote that was key to Democratic victories of old. But her best chance at winning the nomination may lie in shaking loose some extra delegates -- working the levers of the party machinery behind closed doors, just the way Mayor Daley might have done it long ago.

Shares