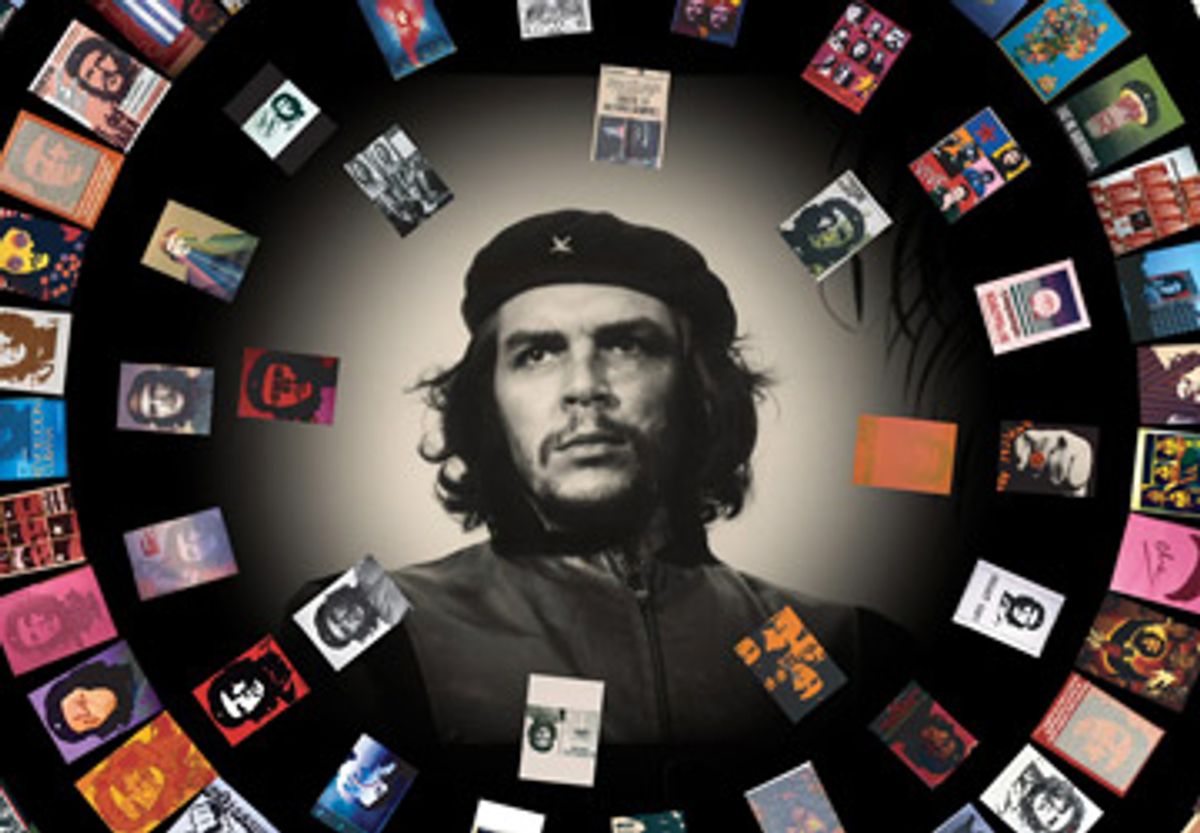

You know the picture all too well: the black beret flecked with a tiny white star; the grim, resolute set of the mouth under a patchy, perpetually hip mustache; the soft-looking flyaway locks of hair lifted as if by the breezes of change. And in those upward-cast eyes? Fury, disappointment, determination ... action.

Ernesto "Che" Guevara, the Argentine-born Cuban revolutionary now dead more than 40 years, is everywhere. His iconographic image -- a photograph snapped at a mass funeral in Havana by Alberto "Korda" Díaz Gutiérrez and subsequently co-opted and adapted by publishers, artists and pretty much anyone with a Xerox machine -- has long been a symbol of protest and the little guy rising up against the ruling power. Today, it gazes at us from T-shirts, posters, album covers, coffee mugs, key chains, beach towels, beer bottles, cigarette packets, bikini bottoms -- and even, briefly, an advertisement for Smirnoff vodka. Korda's snapshot of Che, which he titled "Guerrillero Heroico," may well be the most widely reproduced image in the history of photography.

Why this image? Why Che? Those are the questions Trisha Ziff and Luis Lopez set out to answer with their fascinating documentary "Chevolution," which this week played to sold-out crowds at the Tribeca Film Festival and will be shown in June at the Silverdocs festival just outside Washington, D.C. The film, which evolved from a book and museum exhibition by Ziff that has traveled the U.S. and is currently touring Europe, examines the image's power -- the mythology of the man within the frame and the vision of the man who snapped it -- and traces its journey from the pivotal revolutionary moment it was taken in 1960 to its first publication on the day of the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 to its resurrection on the occasion of Che's death in 1967. It looks at the "perfect storm" of events that led to the photo's proliferation. Along the way, Ziff and Lopez spoke not only with Che biographers and historians, but also his friends, Korda's family and colleagues, artists who have used the image in their work, young people who have embraced the image, others who shun it -- and, yes, a few Che T-shirt wearers with no idea who Guevara was or what he stood for. Also in the interview mix: Gerry Adams, weighing in on the image's power in Ireland; Antonio Banderas, who played Che in "Evita"; Gael García Bernal, who played him in "Motorcycle Diaries"; and Bolivian Sen. Don Antonio Peredo.

Salon was curious about Ziff and Lopez's perspective, so we caught up with them by phone mid-festival.

Trisha, what brought you to curate an exhibit and make a film about the phenomenon of this one iconic photo? What was the moment of inspiration?

Ziff: Really the whole thing began in 2001 when Alberto Korda died. I had met him a few times in Mexico and I was reading the obituaries. Here was a man who'd photographed all his life and he was essentially being remembered for a single image. What impacted me was how somebody's life in our culture is just reduced down so drastically to very specific things. It's almost like we become our own commodity. And obviously in his case the world remembers Korda for taking the Che image. So the representation of his life was really a 60th of a second. That had a real impact on me -- that fleetingness of our reality.

Right, we really never know what we'll be remembered for, which moment will define us.

Ziff: We think having our children or something else we did is what made our lives and who we are, and yet the world sees things very differently. That discourse in my head got me thinking of the image. And I tried to write a short story about it and failed miserably because essentially I'm a curator, so I thought, well, I wonder what would happen if you did an exhibition about only one image. I wonder if they -- the viewer, the audience -- would find it interesting enough. So it became a curatorial exercise for me: Could I do that? Then it began as an exhibition at the California Museum of Photography in Riverside -- and it spiraled out of control, which is what happens with that image. It's amazing. It's like a rolling stone. It just goes on. And that in some ways has happened with the film now too.

The image really does seem to have a life of its own -- or really many, many lives: as a sign of political protest, an image in pop art, a fashion statement. Can you talk about the factors that led to its proliferation?

Ziff: I think there are very specific elements that are in many ways serendipitous. The image was taken in 1960 at this very powerful moment, when a ship bringing arms to the revolution exploded in Havana harbor. Castro thought it was the work of the CIA -- they call it this big terrorist act against the Cuban people at the beginning of the revolution -- though it's never been proved that it was. But it was a mass funeral. It was a huge moment, a watershed moment in the history of the revolution. The image was taken at the moment that Cuba turned to the Soviet Union for help, obviously before the missile crisis.

It's on the roll of film along with all the other images Korda took that day of Castro holding up the different explosives that were found on the boat. And Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre were in Cuba at that time too and they're also on that roll of film. So you have this kind of historic roll of film, but [the Che image] never spoke to the precise moment -- it wasn't published the next day in the newspaper. And then when it is published, it's published as a kind of stock head-shot of Che Guevara, advertising a conference that he's going to speak at -- and the time it's published is the day of the invasion of the Bay of Pigs. So you have this incredible moment when it's taken and this other very important historic moment in the beginnings of the revolution and the invasion. And then it kind of gathers momentum, and when it's published the third time it's in the context of the death of Che. It's held high on these placards protesting the murder of Che by the CIA in essence with the Bolivian Army, and that's a moment that explodes in itself. So context is a huge part of the image.

And yet it has spun way out of its original context ...

Ziff: It did that early on. In '68 it was already becoming an iconic image of protest and change outside the context of his life. Of course all the commercialization came later. The image was almost like the resurrection -- the image sort of left the body of the man and immediately became iconic in that way, but very specific to what was taking place in Europe. The critique of the Soviet Bloc, the right to vote in Ireland, the anti-Vietnam War protesters in the United States, the anti-military movement around the Olympics that was taking place in Mexico: It was about Che and yet it wasn't. Very early on, it wasn't.

In some contexts, who Che was is still relevant to the image's power, yet the image has moved beyond the person who took it and the person in it.

Lopez: What we try to explore in the film is that there is a mythology that grows from Che and it happens in all sorts of ways in different cultures, and that's one aspect of it. And there's also this development of the icon itself. And what's interesting to me is that there's this open source where no one really specifically controls it. And it keeps changing and remodifying. It becomes this open vessel that's constantly evolving without one person or group really dictating where it goes.

Let's talk about the things that contributed to this historic level of proliferation: the lack of copyright in Cuba at the time; Korda's decision to give it away to Italian publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who widely reproduced it on posters; the high-contrast version Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick designed "to breed like rabbits," to name just three. Can you trace the mechanics of the proliferation of the image?

Lopez: I think there were several factors that caused the image's explosion that sometimes we discuss as a perfect storm. It's almost like it could only happen with those sets of circumstances present. There is Che and his mythology and legacy, but also there's other factors. Like the lack of copyright at the time in Cuba, which helped it to be passed around and dispersed quite freely. Other things that we touch upon: the cult of celebrity that was developing at that time, with young heroes and people having posters of James Dean and Elvis and Marilyn Monroe. Another factor is the development of pop art and Andy Warhol taking images of historical figures or popular culture figures and creating art. There's also the era of protest: Prague spring and Paris and Mexico City and Berkeley. So there are all these factors that came together on this one image that helped it explode.

It's interesting now that Korda's estate is trying to protect the copyright and prevent unauthorized uses of the image -- and that Korda himself successfully sued Smirnoff to stop the company from using it in its vodka ads a few years back. The film, I thought, didn't really take a firm position on that. Was that a deliberate choice?

Ziff: From my point of view as someone who's worked with photography and photographers for 30 years, I have a very clear position, which is honoring the rights of the photographer, the rights of the photographer's family, copyright law. This is such a unique image in that so many people do believe it's public domain, and in the film we give them a voice to say that. And then at the end we come back and we give Diana [Díaz, Korda's daughter, who oversees his estate] her voice. I mean there is massive debate today in Cuba about who owns that image: Should that image be a free image for the Cuban people to use and represent the revolution or should it remain in copyright to the estate? It's a pretty cut-and-dried debate because we do have international laws and Cuba now acknowledges those laws. And Diana is absolutely within her rights to implement those laws as any holder of copyright would be.

You also include the voice of a Cuban-American, a young guy talking about his negative associations with Che -- his embrace of armed conflict, the violence. But you didn't dwell on that perspective too long. Was that also a deliberate choice?

Lopez: First and foremost we wanted to explore the phenomenon of a photograph and an icon. We wanted to explore why did this happen, how did this happen. At the same time we felt it would be irresponsible not to give some other perspectives. We had some understanding that there are opposing ideas and voices in all of this.

I'm kind of curious about all the man-on-the-street interviews with people wearing the Che T-shirts who have no idea who he is. I'm wondering about the process of finding those people. I'm guessing it wasn't very hard to do.

Ziff: We went to gathering spots. At Venice Beach, we waited about five minutes for a Che T-shirt to come along. Maybe we were very lucky, but they happened pretty quickly in London, in different places. What happens is once you become sensitized to the image, you hate it, because you start seeing it everywhere. You realize our world is saturated by Che T-shirt wearers. So it wasn't that difficult, but it was interesting the level of ignorance.

I would say it's culturally specific, too. Because if you were to walk through the streets of Belfast or Dublin or Mexico City and you ask people "Who's on your T-shirt?" they'd know. I think it's quite culturally specific to the United States and to education in the United States and what people are taught and not taught in the States. It's quite mind-boggling as a non-American.

On my way to New York for the festival, I sat next to a Tibetan monk on the plane and I was looking at some of the early reviews with the Che image on them. He leaned across and he said, "I see that man in so many countries, but not in my country, not in Tibet. Is he a musician?"

Do you think the image has lost or gained power in its explosion? Or both?

Ziff: I think both. It's changed. It metamorphoses. It travels. It takes on new meanings. It gets attached to different moments. In Mexico City, you don't really see that image without seeing the image of the Zapatistas, and it becomes an image about indigenous voices and the rights of the indigenous and independents. The schoolteachers strike in Oaxaca, it's the same thing. It becomes this strong image of a struggle and specific in some contexts and in others this much more generic image used in protests we wouldn't even associate with it, like green issues or whatever.

What are some of the strangest things you've seen the image on?

Ziff: A doormat. Wipe your feet on Che Guevara!

Lopez: I just saw a "Che-r" T-shirt: Cher's face with the beret.

Ziff: You see that a lot. People just put a black beret and a star on other people: Libera-Che, Che-ney. You can go on and on Googling them.

There's your next exhibition.

Ziff: Oh, please God, no.

Do you think the image will ever run its course? Is there an end?

Lopez: I don't think so. It seems to me that the image just has such staying power and resonance. I think certainly not in my lifetime. It won't go away.

Shares