In this summer of Dark Knights and Hellboys and Iron Men, it's refreshing to be reminded -- as we will be this weekend, with the opening of "The-X-Files: I Want to Believe" -- that not so long ago, there was a science fiction series with a woman at its core, a heroine whose major goals were more about disproving the existence of extraterrestrial life than marrying Big, a chick who spent more time chasing fluke worms down toilets than trying on shoes.

I was crazy about "The X-Files," Fox's pre-9/11 ode to trusting no one. I taped every episode. I watched many of them repeatedly. I borrowed friends' tapes and purchased some of my favorite episodes when they became available. I saw the confounding first "X-Files" feature, "Fight the Future," in the theaters. Twice. I still think of 10:13 as a lucky number, on a clock or calendar, and I still occasionally address e-mails to friends who knew me at the time with "Mulder, it's me." Perhaps the biggest sign of my devotion was that I forced myself, balefully, to keep watching the show to the bitter end, after David Duchovny took off and pallid young Mulder and Scully imitators were hired to generate new heat.

No, I never wrote fanfic or had an online alter ego named after Scully's dog, "Queequeg"; I didn't name my cat Skinner, though let me tell you, it crossed my mind. Eight years out, I can't imaginatively conjure up the face of the Well-Manicured Man, or tell you what the deal was with the alien black oil.

But I was never in it for the conspiracy, the Syndicate, Deep Throat, the Cigarette Smoking Man or the array of bat boys, robotic cockroaches, Satanic cheerleaders or Mexican goat suckers that waltzed menacingly across my screen every week.

I was there because I knew, eventually, my heroes would get it on. And because I was totally enraptured by special agent Dana Scully.

It probably wasn't supposed to be that way. Duchovny's Fox Mulder was, after all, the centerpiece of the narrative: the brilliant, wounded, lonely man, who spends his life trying to sort through the trauma of his sister's disappearance and prove that he isn't crazy for believing in aliens, ghosts and El Chupacabra (the Mexican goat sucker). And it didn't hurt that Duchovny was basically a walking pheromone, all languid eyes and long-necked eroticism.

Sure, Mulder was hot, and made you want to heal and help him and go with him to the Andes in search of the yeti or whatever it was he planning to do with his three-day weekend.

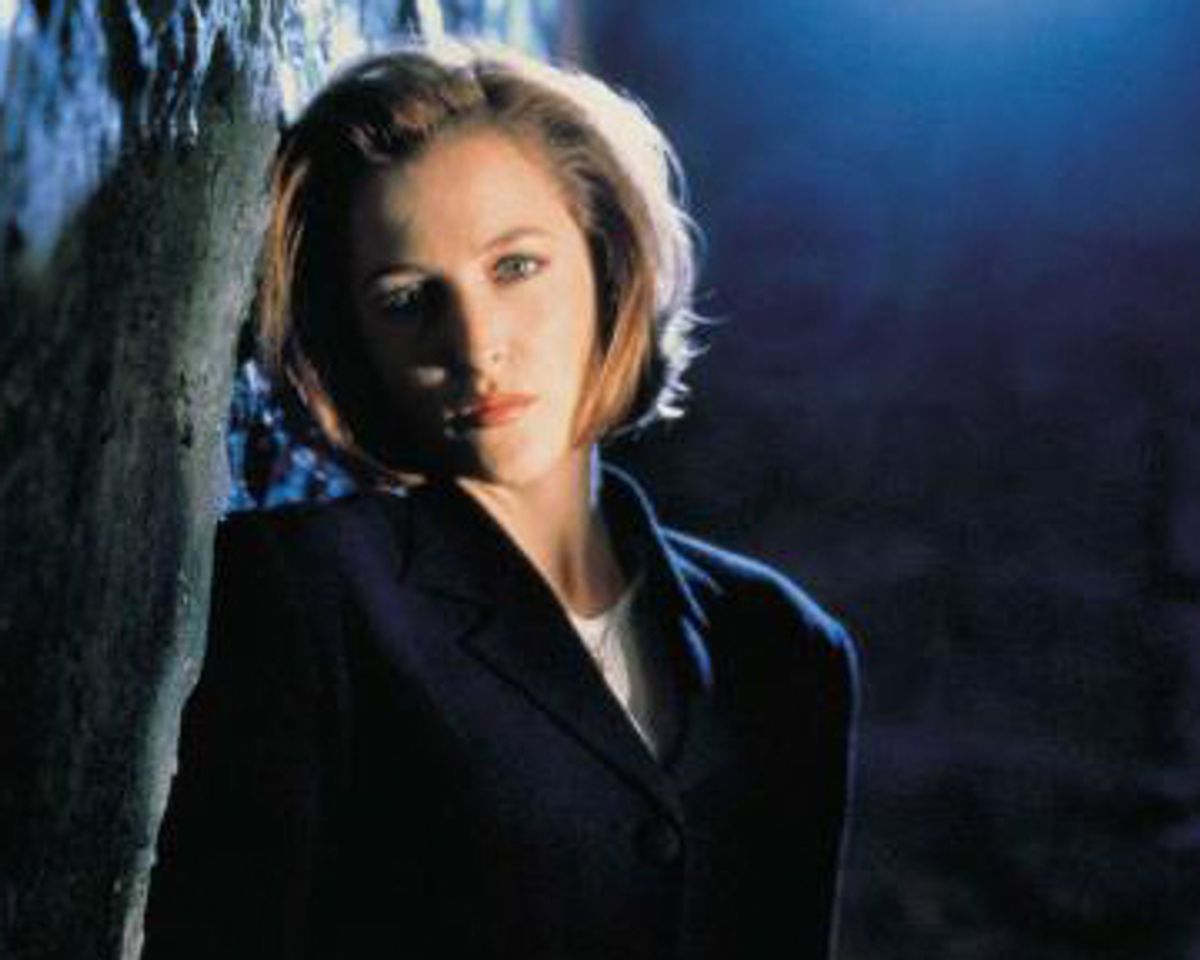

But the one I would have gone to the ends of the earth for was Scully. Patient, long-suffering, geeky forensic pathologist Scully, so short and tucked and tailored. Given such a tough role -- as the woman brought in by the FBI to be the minder and school marm, as Mulder correctly says in the first episode, to spy on him -- Scully was supposed to be able take away his toys and crush his dreams of ghouls and goblins.

Who wants to be the skeptic, the killjoy, the buzzkill? Gillian Anderson, plucked from obscurity in her early 20s to play Scully, should have initially petitioned for a special Emmy category that rewards excellence in the field of lip biting, sideways casting of the eyes and exasperated bowing of the head.

But as the show matured, it was Scully -- the cerebral head of the X-Files, torn between her Catholic faith, her scientific impulse to explain away the inexplicable and her affection for her partner -- who was destined to become the (still cerebral) heart of the show.

The very fact that her character was such a hard sell made her repeated brushes with the supernatural all the more powerful. Mulder's desire to believe was so expansive, his credulity so flexible, that it's not as though he was ever going to have either shaken from him. But Scully's surety was solid, stable, rigid; every time she saw something she thought she'd never see, we saw it crack, sparks fly from it. She was forced to question herself, grow, change. In short, she got the better arc, and her journeys were always, by dint of the setup, more intricate and moving.

There's a beautiful scene at the end of an episode from Season 3, "Clyde Bruckman's Final Repose," about a man who can foresee when and how everyone will meet his or her end. In it, Scully, who of course initially doubts him, watches as one of Bruckman's unlikelier predictions -- that she will wind up in bed with him, holding his hand tenderly as tears stream down his face -- comes true. Anderson's pale young face opens wide with grief and realization: grief for the man she'd taken for a kook, realization that he had been for real, and also that the other prediction he'd made about her was that she would never die.

Scully, we are to believe, is immortal; the series hinted at it at various other points, especially in a stunning sixth-season episode in which she looks away from death as it approaches her. It's a testament to the strength of the character that as the other unwieldy mythologies of "The X-Files" -- aliens and government conspiracies and black oil! -- inevitably crumbled under the weight of their own convoluted expectations, the mystery and mythos surrounding Scully grew steadily stronger.

Early episodes of the show look so dated now -- check out their toaster-size phones and Scully's ill-advised jewel-toned pantsuits -- but "The X-Files" was innovative television when it debuted, dealing as it did with issues of science, faith and distrust in government that in a post-9/11 world would probably have landed Fox Mulder deep in Guantánamo.

Scully certainly did her time as a damsel in often soap-operatic distress: She was abducted, her eggs were harvested, her sister was killed; she had cancer, a chip was implanted in her neck, and she was dragged to a spaceship in Antarctica, where a gross-looking tube was stuffed down her throat and she was pumped full of an alien virus. But though her reproductive system was the depressing locus for much of her trauma, she wasn't alone in her victimhood. Mulder had nearly as many indignities foisted on him. Abduction, check. Dead sister, check. Alien virus, check.

In fact, the show was exceptional in its willingness, if not to turn gender conventions on their head, then at least to level the playing field. The producers could have insisted on a more standard-issue duo, an alien-loving nerd and a bombshell lady scientist. Instead we got the slightly repressed (or at least sharply coifed and primly manicured) but socially capable leading lady and her porn aficionado partner, leering but ultimately unlucky with the ladies. "X-Files" creator Chris Carter complicated the roles of his wary protagonists further by making Scully the rational, resilient, mature one and her partner Mulder a gullible, sensitive, doe-eyed and slightly laughable foil.

The pairing, based mostly on the dynamic between actors Anderson and Duchovny, crackled, and the show had at its core a professional relationship that was not just sexually, but romantically, electric. Of course, back then, when we all walked a mile to school and programs started the season in September and finished them in May, slow-burn television relationships burned really slowly, especially in comparison with today's short-attention-span theater, when an unrequited prime-time couple can maybe make it to sweeps before kicking off their panties.

Not only did the sparks between Mulder and Scully fly fast and far, but the drawing out of their relationship allowed their audience to fall for them too, despite the irritating imperfections of both character and plot.

Scully was a leading lady to fall for, a smart-girl icon who was (and would still be, alas) a rare television bird: professional, independent, unsentimental. She liked boys' things: Her favorite movie was "The Exorcist," her favorite book the phallic classic "Moby-Dick"; her nickname from her father was Starbuck; she wrote her thesis on Einstein's twin paradox. She was the opposite of squeamish. In possibly the best "X-Files" episode of all time, the vampire farce "Bad Blood," there is an ur-Scully scene: She is doing an autopsy after a long day of chasing the undead through a small Texas town. Annoyed, she sighingly hoists the departed's heart, lung and intestines onto the scale, reading their weights into a tape recorder. Then she opens up the victim's stomach and starts poking around with her scalpel to determine his last meal. "Pizza, topped with pepperoni, green peppers, mushrooms." Here she pauses, looks up briefly from the bloody innards. "Mushrooms. That sounds good." She orders a pizza.

Today's television is not without its Scullys -- "Law & Order" ladies who crack skulls and chase bad guys in Jimmy Choos. But they all feel like tall, skinny, limp knockoffs of the original. Dana Scully was not standard television beautiful, but a diminutive pre-Raphaelite, pale of skin and red of hair, who could give equal amounts of soul to lines like "Nothing happens in contradiction to nature, just in contradiction to what we know of it" and "Well, seeing as how it's Friday, I was thinking I could get some work done on that monograph I'm writing for the penology review: 'Diminished Acetylcholine Production in Recidivist Offenders.'" A woman who, when asked by her pestering partner to examine a cadaver's head just one more time for a set of horns, can snap on her gloves and mutter "Whatever" like she really means it.

Of course most of the credit here goes to Scully's portrayer, Anderson. I was always keenly aware of the discrepancy between the entertainment press's reactions to Anderson and Duchovny. The latter, a Princeton grad who was an English Ph.D. candidate at Yale (his unfinished dissertation was to have been on morality, magic and technology and "Gravity's Rainbow"), was always breathlessly congratulated for his special intellect and pedigree. He seemed to accept the media's wide-eyed adoration with self-assuredness, feeding reporters lines about Marvell or Milton. Anderson, by contrast, was unapologetic about being the wifty one, a remorseless wild child whose giggly demeanor and pseudo new-wave spirituality always made her appear, in interviews and on talk shows, the polar opposite of her character.

But I always thought that for Anderson to so beautifully embody Scully -- a character so distant from her own experience -- meant that she was the special one. Intervening years have put a satisfying spin on their real-life personae. While Duchovny, who had such a bright future ahead of him that he (discerningly) left the show early, flopped around in middling movies until finally finding his natural home on the softcore narcissism-fest "Californication." Anderson, meanwhile, has built a career on an immaculately edited collection of sophisticated material. The former punk rocker may still be wifty, but she is practically a poster child for highbrow period piece drama, and has turned in gorgeous performances as Lily Bart in "The House of Mirth," as Lady Dedlock in "Bleak House" and as a doctor in the brutal Idi Amin biopic "The Last King of Scotland." She even did a terrific sendup of herself in "Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story."

This weekend, she'll be bringing all those chops back to the role that made her, and that's good news. In an entertainment world where women are disappearing from multiplexes, where men bulk up as superheroes while women don't eat but sip pink drinks, we need to remember that there was once a very short heroine who hunted monsters and talked about Einstein, who kicked ass and questioned her faith, who went to work with a man she loved but didn't rip his shirt off over lunch, who didn't want to believe, but opened herself nonetheless to possibility. We need Scully back, even for a moment.

Shares