For every Barack Obama or Abraham Lincoln, this state produces a dozen Rod Blagojeviches.

Here's a short quiz. Which of the following is statistically more likely to land a Chicagoan in jail: a) joining the Gangster Disciples, b) selling crack on a West Side street corner, or c) becoming governor. The answer is c, of course, which makes me wonder. If governing Illinois is such an at-risk occupation, why don't we just abolish the job and replace it with a board of directors or a court-appointed supervisor?

It's almost hard to blame Blagojevich for the trouble he's in. The odds were against him from the beginning. Three of his last six predecessors -- Otto Kerner, Dan Walker and George Ryan -- have gone to prison. Ryan, who as secretary of state sold drivers' licenses for bribes, is languishing in a federal pen in Wisconsin, pining for a Christmas pardon from President Bush.

When Blagojevich was elected, he promised to clean up the state's "pay to play" political culture. But nobody really believed him. He was the governor, for God's sake. The governor is the last guy who would do something like that. Who benefits more from shaking down political contributors?

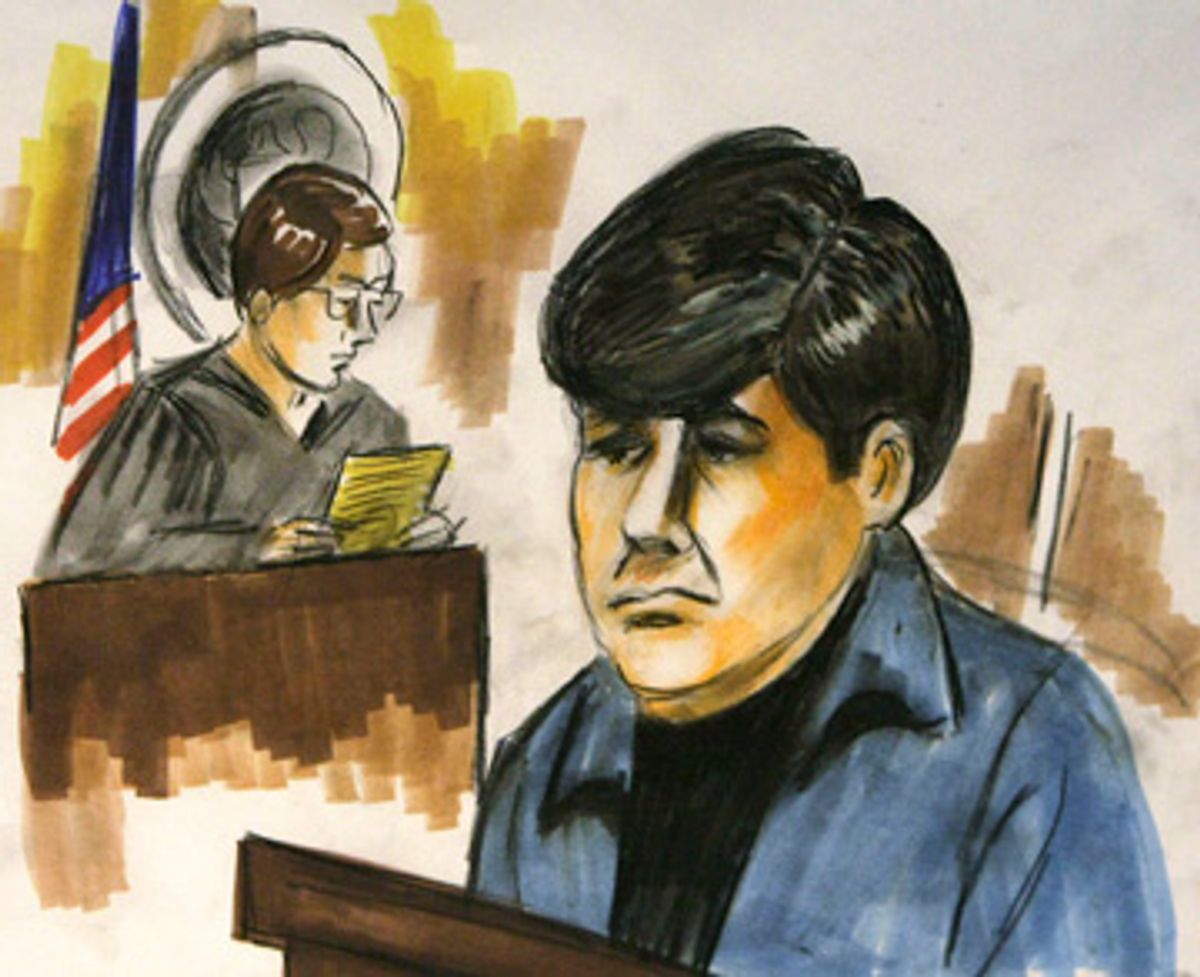

I never expected Hot Rod to get into a mess this hot, though. Frankly, I always considered him an amiable goof obsessed with hair care and jogging. Not smart enough to be competent, but not cunning or venal enough to hatch a Nixonian scheme like peddling a U.S. Senate seat as though it were a stolen flat-screen.

Rod Blagojevich's motivating characteristic is vanity. And judging by the complaint against him, his vanity -- which created a thwarted desire for the office Obama is about to occupy -- may have contributed to this scandal.

Blagojevich may not be bright, but he's good looking, and he's lucky. He got his start as a political gigolo. The son of a Serbian immigrant who worked in a steel plant, Blagojevich had no political connections. So he married a boss's daughter. Putting his handsomeness to work, the young attorney attracted the attention of Patricia Mell, offspring of Richard Mell, one of Chicago's most powerful aldermen. In Chicago, it's not enough for a ward boss to just run his ward. He has to have guys in the state capital, Springfield. And Washington. Blagojevich was out jogging one day when he got a call from his father-in-law: How would you like to run for the state house? Blagojevich won that race, and four years later, he was elected to Congress from the fifth district, replacing the Republican who had briefly replaced Dan Rostenkowski. Who was, of course, at the time, in prison.

When Blagojevich ran for governor, in 2002, he squeaked through a primary against a popular Chicago school superintendent and an African-American attorney general who siphoned off just enough of the urban vote. The general election was a breeze. He was running against the legacy of George Ryan, still in office but already under investigation -- and a Republican opponent named Jim Ryan, who was so embarrassed by the coincidence that he only used his first name on yard signs.

Blagojevich had survived the primary with the votes of downstate Illinois. It's an oft-ignored part of the state, and once he was in office, Blagojevich ignored it more than any governor in Illinois history. He refused to live in the governor's mansion in Springfield, flying home to Chicago every night to tuck in his daughter. Small wonder that last week, while driving home from Peoria, I saw a "BUCK FLAGOJEVICH" bumper sticker.

Illinoisans have always had a sense that Blagojevich was shady, but prosecutors had never managed to pin anything on him, in spite of a lengthy federal investigation. In 2006, he won re-election in a year when no incumbent Democrat lost a race for governor, senator or congressman. His opponent, state treasurer Judy Baar Topinka, was an abrasive, orange-haired cross between Marge Schott and a chain-smoking cocktail waitress. Her successor as state treasurer had to replace all her office furniture (it had been ruined by dog hair and cigarette smoke). Blagojevich boasted that he had the "testicular virility" to make tough decisions.

Earlier this fall, when the Chicago Tribune asked him to respond to a poll showing he had an astounding 13 percent approval rating, less than half of George W. Bush's, Blagojevich said this:

"I love the people of Illinois more today than I did before. And if it's a case of unrequited love at this point, I'll just have to work extra hard to get them to love me again."

Now his approval ratings will probably drop into single digits. But Blagojevich's vanity, however delusional, is not to be underestimated. Rod is so vain he thinks this sentence is about him. He's a huge Elvis fan, and his state troopers reportedly have a brush handy to keep his dark, King-like mane in place.

From the moment he entered office, Blagojevich wanted to run for president. The original plan was 2008, but then he was upstaged by a man who, in 2002, was a mere state senator. (According to the complaint, he contemplated appointing himself senator to set up a 2016 run.) That may be why Blagojevich was so vehement in demanding favors in exchange for appointing Valerie Jarrett, Obama's handpicked successor. As the complaint put it:

ROD BLAGOJEVICH said that the consultants (Advisor B and another consultant are believed to be on the call at that time) are telling him that he has to "suck it up" for two years and do nothing and give this "motherfucker [the President-elect] his senator. Fuck him. For nothing? Fuck him."

It was the one power he still had over Mr. President-Elect, and he was determined to wield it.

The dashing of Blagojevich's ambitions was good for the job prospects of some other people, however. Maybe not for Senate Candidate 5, who Blagojevich allegedly said was open to, yes, "pay for play" in return for Obama's old seat. But it may help U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald.

At his Tuesday morning press conference, U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald declared that Blagojevich's conduct "would make Lincoln roll over in his grave." That was overwrought, since Lincoln appointed his campaign manager to the Supreme Court.

Announcing the charges before Blagojevich appointed a senator -- and before Obama takes office -- was a clever move by Fitzgerald, a Republican appointee who would be expected to resign under a new administration. Fitzgerald's nomination -- by Obama's predecessor, Peter (No Relation) Fitzgerald -- was considered a thumb in the eye to the Chicago Machine. Cook County Democrats covet control over the U.S. attorney's office, because it's the only law enforcement body with the independence to look for sleaze in local government.

There's little doubt that Chicago Democrats were thrilled about having a Chicago Democrat in a position to appoint the next U.S. attorney. Now Fitzgerald may be impossible to get rid of. He's popular with liberals, because he convicted Scooter Libby of perjury and obstruction of justice in the Valerie Plame affair. And replacing him with a Democrat in the middle of the Blagojevich case may look like a sellout to Illinois' corrupt political culture.

As Fitzgerald noted, he didn't want to wait until "March or April" to file the complaint. Because if he hadn't filed it, he might not have been around in March or April.

Blago's fall was also good for Lt. Gov. Pat Quinn. There's a saying in Chicago politics: "Don't make no waves. Don't back no losers." With Blagojevich looking like a loser, the entire political establishment rallied against him, starting with Quinn, who has the most to gain from Blagojevich's removal. Quinn actually is a reformer -- he made his name by passing a referendum to shrink the size of the General Assembly -- but he's also a quirky gadfly who has spent his entire career stuck in second-tier state offices. He won his current job without Blagojevich's help -- candidates for lieutenant governor compete in a separate primary -- so he's not bound to defend his boss. At his press conference, Quinn revealed that he hasn't spoken to Blagojevich "at length" since the summer of 2007.

Waving a "tattered version of the Illinois constitution," Quinn suggested the governor should "do the right thing and step aside." Which would give Quinn the power to appoint a senator -- an office he himself ran for in 1996. If Blagojevich won't go quietly, the state supreme court could rule him unfit to serve.

"I don't believe he should in any way, shape or form exercise the appointment power of a U.S. senator," Quinn said. "To have [Obama's] vacated seat subjected to any kind of wrongdoing is shameful."

Quinn was followed at the lectern by state Rep. Jack Franks, who announced that he would introduce a bill to strip an indicted governor of his power to appoint a senator. The state would hold a special election instead. The earliest that could happen would be Feb. 24, the day of local primary elections, meaning Illinois would be without a senator for a month and a half.

That's better than a tainted senator, the feeling goes. The only bright side in all this: At least everyone knows how to pronounce our governor's name now.

Shares