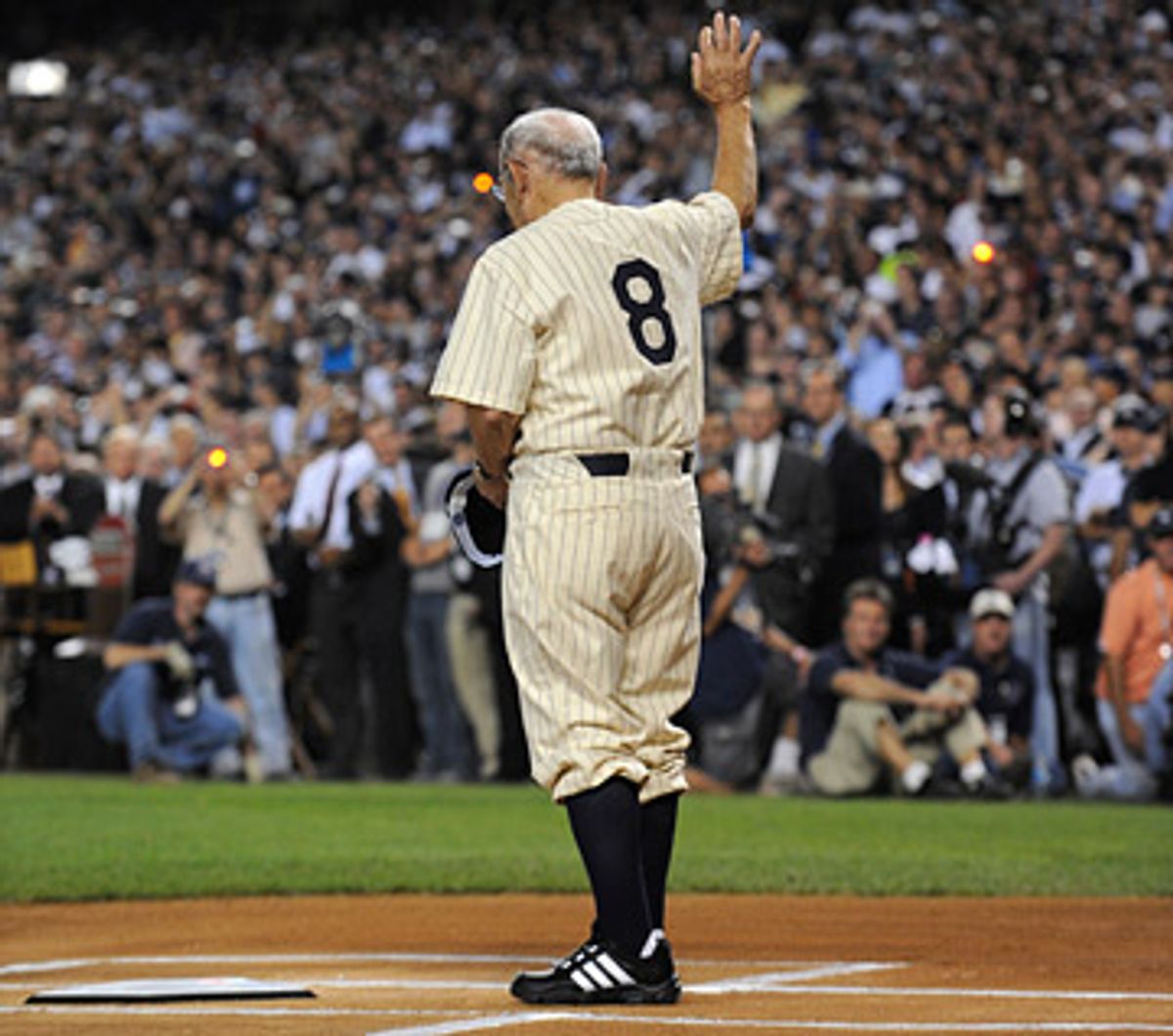

Allen Barra says a case can be made that 83-year-old Yogi Berra was the greatest catcher in baseball history. And no ex-ballplayer is more famous today, not even Willie Mays.

But a few years ago, fresh off a book about Bear Bryant, Barra noticed that there hadn't been a definitive bio of Yogi. He set out to fix that, and the result is the new "Yogi Berra: Eternal Yankee."

Yogi's best known to younger generations as a lovable lunkhead, the idiot savant who talks to a duck on an insurance commercial, who said, "It ain't over till it's over" and "You can observe a lot by watching." Then there are the malapropisms that make a weird kind of sense when you think about them: When you come to a fork in the road, take it. Half this game is 90 percent mental. I didn't really say everything I said.

But, as Barra points out, Yogi's been a success at almost everything he ever tried. Pitchers who were brilliant when he was behind the plate never did anything much when he wasn't. Whitey Ford, one of the greatest left-handers ever, often says he never shook off one of Berra's signs, and Don Larsen has said the same thing about his World Series perfect game.

Berra won more World Series than any other player. He won three Most Valuable Player awards and appeared in 17 straight All-Star games. He was the leader and the on-field constant of the only team ever to win five straight World Series, the 1949-53 New York Yankees.

He was only the second manager ever to win a pennant in each league. He was a great coach and he's a good businessman. And just about everyone who's ever dealt with Yogi Berra has come away not just liking him, but respecting his decency, his integrity and his intelligence. There's more to Yogi Berra than meets the eye.

I talked to Allen Barra about his new book last week. Some full disclosure: Barra's a former Salon columnist who still freelances here. He's a colleague and a friend. I called him at home in New Jersey.

I remember you told me a couple of years ago that you were starting this book and you were saying that it was amazing that there's never been a serious biography of Yogi Berra. And after having read yours -- don't take this the wrong way -- but I kind of get why. There's no big flamboyant conflict and drama in his life. Did you find that that was something you had to overcome, that lack?

Well, let's put it this way: There are certain eras in sports and baseball when that's a plus. And it struck me a couple years ago, even then, that this would be one of those times. It might be nice to read about a guy that there are no big dramatic issues concerning. That's why I liked the idea of writing about Yogi.

I wanted to write about a life in baseball and keep it apart from huge contracts, drug issues, everything that's been plaguing the game over the last couple of years. And, happily, he's also one of the greatest players in baseball history, and maybe the most underrated. Which seems funny when you think about it, because he's probably the best-known former ballplayer around and yet he's underrated. He's underrated as a player.

You wrote a few years ago that he was the most valuable player in American team sports history.

I don't think that anyone would deny that there's something to be said for the idea of intangibles, contributions that can't necessarily be measured by statistics. I just don't know -- since they can't be measured, how do we know what that would be?

Sean O'Faolain, Irish novelist, once wrote about an Irish woman, a peasant woman. He said, "Do you believe in the fairies?" And she said, "I do not." Period. "But they're there." I feel the same way about intangibles. I don't know if I believe in them. But they're there.

If somebody's contributing something in the clubhouse, some added little bit of knowledge, some experience he passes on, some kind of thing that pulls the team together, then I think that guy's teammates would be the people to judge whether or not intangibles exist. And everyone who has been with Yogi Berra insists that he brings something extra to the table that can't necessarily be quantified.

Now, what are we going to do, argue with those people? I mean, it isn't like Yogi doesn't have the rings to prove it. And his contributions as coach and manager. So, whatever it is that's out there that he contributes that you can't see statistically, Yogi obviously has it. But that doesn't mean that you can't make a case for him with the statistics, which I think are amazing.

It seems like you didn't interview Yogi for this book. I assume he didn't want to talk to you and I wonder if he gave you a reason or what happened?

Who's the great Irish actor in "The Quiet Man"? Barry Fitzgerald. Barry Fitzgerald always says in "The Quiet Man," "I did and I didn't." I was asked not to sit down with Yogi. They said he's getting tired. He's having trouble remembering some of the details of the things he's talked about many, many times. And that's understandable. And that was fine with me. So in that sense I wasn't granted access.

In another sense I was given everything I needed, all the materials. I mean, let's face it: How many more times does Yogi need to talk about hitting the home runs off Don Newcombe? Or something like that. There are scores of taped interviews, in-print interviews, newspaper stuff, magazine stuff. All I needed was access to that.

Now, in another sense I did get access to him. I was invited to all the events at the museum. For instance, in the back of the book there's an appendix from the [showing of the tape of the] Don Larsen perfect game. Larsen and Yogi showed up at that and I was allowed to ask all the questions I wanted. And I got some good stuff out of that.

So there were several times over the years, the World Series broadcasts at the museum with Yogi, there were local high school events he would do with Larry Doby around here that I taped. I got plenty of conversations in with him. We just didn't sit down and retalk these things over again.

Is there anything that, if you could, that one question you would have wanted to ask him that you didn't get a chance to ask?

Here's what I wanted to ask him more than anything else, and I didn't. I was curious to see in his 1989 memoirs, which was not an attempt at an autobiography, it was mostly just reminiscing. He mentions, he says, "A lot of people said they loved Casey Stengel." Yogi said, "I didn't love him, but I missed him when he died."

Yogi and Casey were not joined at the hip, and you get the feeling that over the years there was many times when Casey rubbed Yogi the wrong way. It's interesting that Yogi understood that most of the decisions Casey made were as a manager, not as a friend, and it had to be that way. There was always that distance that you had to keep from the players when you were managing, no matter how much you loved somebody.

And Casey would constantly try -- he tried to push Yogi back to the lineup after an injury on two occasions. "You know, we need you. What's the matter with you?" And he even -- one of the players told me that Casey had talked him into needling Yogi to try to get him back in the lineup. I mean, that's a hell of an admission. You know, the manager's using me to try and, that they even put out the feeler, the idea to Yogi that he might not get a full World Series share one year because he didn't get back in the lineup.

And Yogi was absolutely adamant. Here's a guy that's one of the most durable players ever. A tremendous team player. But he, by God, was not going back in that lineup until he knew that his injury was healed. A very smart decision, not only for himself, but for the team. But you've got to remember that Casey's thinking, "If we don't win, I might get fired." So he had his interests, and Yogi had his and Yogi was smart enough to know exactly where they differed.

I would have asked, in answer to your question, I would have asked Yogi to talk more about his relationship with Casey and when he became a manager himself did he understand that you have to make decisions based on what management wants rather than what the individual player might want.

It's really sort of amazing that he was so close to Casey Stengel, so closely tied to him, and they both have that same thing, they're thought of as clowns and they're remembered for the silly things they say, and they both have a lot more meat on their bones than they're given credit for.

How could they not? You have the most successful manager in baseball history and the most successful player in baseball history. And it's amazing to me that there are still people that don't give them their due for what they did. Supposing they weren't clowns. You know, supposing they were classic smart guys. Let's say the Gene Mauch mold. How much more could they have won? How much better could they have done than they did?

Here's wishing for them that they didn't have all the success Gene Mauch had.

That's right. And I think it's interesting to note that here's Mauch in '64, his team goes through one of the two or three greatest collapses in baseball history, and Yogi's, on the other hand, his team makes a great second-half comeback, pulls together and wins. So what are we saying? That the Yankees would have been better that year had Yogi been smarter? Or more of a classic manager? I don't think so.

Well, it's a hobbyhorse of mine that Gene Mauch is the most overrated manager in baseball history. But also, you know, Berra's so successful and Casey was so successful. I wish, on the other side of the coin, players and managers today would take a look at that and lighten up a little.

Well, yeah, there's a lot to be said for that. And also for having faith like Yogi did. Once you made a decision sticking with it and riding out the storm of controversy, all the people that disagree with you. And every circumstance where Yogi did something like that he turned out to be right.

The thing that surprised me, and I'm about to ask you if anything surprised you, the interview question there. The thing that surprised me was how often the sort of a recurring theme of Yogi sticking to his guns, starting from when he was a teenager and Branch Rickey tried to sign him and the famous story where Joe Garagiola got 500 bucks and Yogi didn't so Yogi said no. I mean, all those contract negotiations with the Yankees, it always worked out for him.

You're a kid and you're dealing with Branch Rickey and he offers you a contract but you're not gonna go, because you're absolutely convinced that you're as good as your pal, who got 500. Imagine that, I mean, that takes a lot of guts. I wonder if the one recurring theme throughout this is that Berra's luck was a residue of Berra's intelligence and resolve.

He seemed to have an unerring sense. There doesn't seem to be that point where, gee, I stuck to my guns and I stuck to my guns and boys, I was wrong. I mean, we just don't have that story.

I see this from Yogi at a very early age, dealing with Branch Rickey. All of these decisions he made, he made on his own. There was nobody looking over his shoulder. They questioned his intelligence, always, right on through to the end of his managing career. And yet, Yogi's decisions were always right. Just as his decisions with pitchers, how to handle 'em, what pitches to call for, were right. He was there for the biggest games in baseball history. And eventually, everybody that worked with him was willing to just, you know, let him call the game.

Let me ask you what I said I was going to ask you, if there's anything in your research that really surprised you, that really stood out, that you didn't know, didn't think would be true.

I'll mention one small thing and then I'll go to a larger one. I did not realize the titanic salary struggles that were going on below the surface. We never do back then, you know. All we think of is how Scott Boras is ruining the game for getting huge contracts for these players.

But you go back then and you see people like [Yankees general manager] George Weiss, who was a penny-pinching bastard, and arguing with Yogi Berra that, "Well, you don't need that extra raise because you got your World Series check." And Yogi's smart enough to come back with, "Yeah, I had something to do with that." Not buying that argument. You know: That has nothing to do with my salary. And how could you possibly have fought back then? Since you didn't have an agent and there was no free agency?

Well, you know, the cleverness of having your picture taken in the paper as a waiter at your friend's restaurant, saying, "Gee, I think I like this life. You know, I'm making good money here, I may not play this year." It took a lot of guts and a lot of smarts. And Yogi won just about all of those battles.

He and Carmen, his wife, were very, very sharp and very smart when it came to the salary fights and they almost always won. I didn't know that Yogi was that shrewd when it came to money and we should have all known, right? Because of all the guys, all the Yankees and all the smart guys in those years, who was the one who became a successful businessman off the field? You know, with his bowling alley and Yoo-hoo soft drink and other stuff. It was Yogi.

Who was the man that hooked up with the great genius of modern advertising, George Lois. The cat food and the other commercials. It was Yogi Berra. So I didn't know that Yogi was that shrewd off the field and took his money that seriously. Good for him.

Overall, though, I have to say that before I started thinking about writing this book I just didn't appreciate Yogi's greatness. I never saw him as the glue that held the only five-time, five-World Series championship team [the 1949-53 Yankees] together.

There were no Hall of Fame pitchers on that team. DiMaggio was winding down. Mantle doesn't start to make a real contribution till about '52. Yogi was the glue, he was the glue all of those years, and when I went up and down the roster and looked at the Yankees pitching staff, year after year, from '49 to 1960, it's amazing how many guys would have never been winners had it not been for Yogi Berra.

So, you know, overall I would say, yes, I would take Babe Ruth, I would love to have Lou Gehrig, I'd love to have Mantle. But I'm not certain that if I was gonna pick a baseball team and I wanted overall value for 10 years, that I wouldn't start with Yogi Berra as my first pick.

With Bear Bryant and now Yogi, you've written about the most famous sports figure in your two home states. Is that sort of a conscious decision?

Yeah, I've covered both sides of my family. I don't know. It's funny how some people ask you how long it takes to write a book like this and I always say 40 years.

I remember as a kid my father took me, we were out West and my father took me to all these legendary places. Deadwood, you know, where all this western lore had come from. We went to the Little Big Horn Battlefield, we went to Tombstone, and I wrote that biography of Wyatt Earp. So I guess to know what I'm gonna be writing about a few years from now, I have to go back 40 years and see what was I doing then. And how long did this idea take to germinate.

I don't know, I don't know what to say except you reach a certain point where you say, "These are colossal figures." In all three circumstances there, with Wyatt Earp and Bear Bryant and Yogi Berra, and you say, "Well, why hasn't anybody done a definitive book on them?" And the only answer I can say to that is that, the answer to that question isn't easily apparent. It takes a while, it takes time for you to get perspective on these people.

Shares