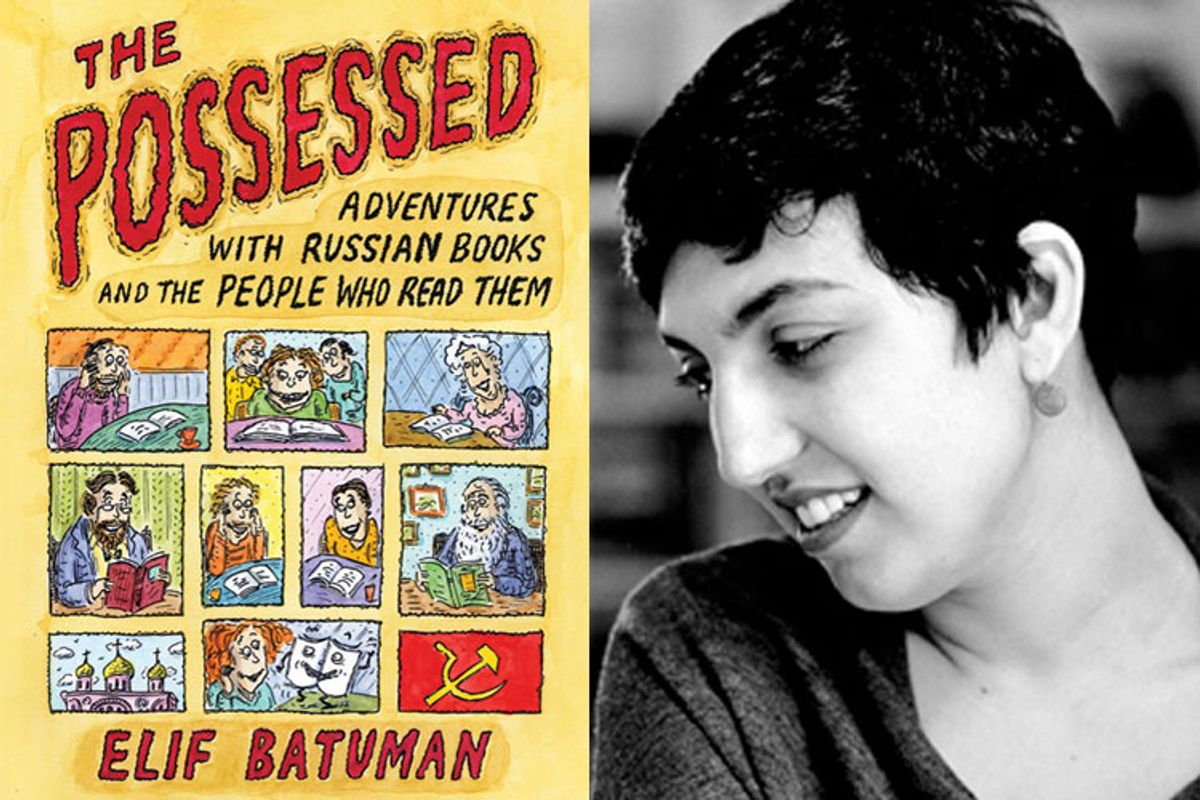

I ought to begin this with a disclaimer: I'm no great partisan of the Russian novel. There are some I love ("Crime and Punishment"), some I admire ("War and Peace") and others I could never finish ("Dead Souls"), but I can't claim to have read very many of them. So when I rave to you, dear readers, about Elif Batuman's hilarious and charming "The Possessed: Adventures With Russian Books and the People Who Read Them," understand that the author has entirely bewitched me despite my relative indifference to her subject. Ten pages in, I already knew I'd read her on pretty much anything.

Which is not to say that "The Possessed" failed to enlighten me about both Russian books and the people who adore them. For a while now, my beef with Russian literature has been that it is too confusing, not because of the names (the usual reason people give), but because of the manners. One character will do or say something seemingly innocuous -- offer another character a cup of tea or compliment him on his hat -- and the other character will react in some extravagant yet utterly unpredictable way, with fury, say, or abject gratitude. Why? I know of only one example in which this sort of thing has been explained: the famous case of Irena, in Chekhov's "Three Sisters," who is distraught to receive an expensive samovar as a gift because (experts will tell you) the urns were traditionally given to older women.

The fact that I could never quite understand what was going on put me off of Russian novels; for Batuman, it's a prime attraction. Her "fascination with Russianness" dates back to her early youth when, as a first-generation Turkish-American from New Jersey, she took violin lessons from a Russian named Maxim. His behavior baffled her, particularly the period during which he exhaustively coached her for a juried examination, repeatedly insisting, "We have to be very well prepared because we do not know who is on this jury." When she turned up for the exam, she found the panel headed up by "not some unknown judge, but Maxim himself."

Captivated, Batuman developed an appetite for what she calls "mystifications." "What I used to enjoy in poetry," she writes, "was precisely the feeling of only half understanding." Most essayists would probably approach the cognitive netherland of semi-communication as a sad and serious dilemma, but for Batuman it's a kind of heaven, lush with comic possibility. Russians, with their unfathomable and melodramatic behavior, strike her as both awe-inspiring and amusing. "The Possessed" describes Batuman's experiences at scholarly conferences where, in the middle of dinner, elderly ladies suddenly say things like "I would like to know if it is TRUE THAT YOU DESPISE ME," and on assignment meeting people who "told me about their dream to reestablish Petersburg as 'the birthplace of ice sculpture.'"

Quite a few of the adventures Batuman recounts, however, took place not in Russia but in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. In her early 20s, as a result of a series of misunderstandings and inexplicable actions, she wound up spending a summer there, studying "Old Uzbek," a language and culture that was half invented, half stolen by the Soviets; it is at once tragic, bizarre and ridiculous. Batuman got interested in the Uzbek language because she'd hoped it would bridge Turkish and Russian, the languages of her heritage and her literary passion, respectively. In Samarkand, a ramshackle town with a glorious, if very distant, past, she trudged along unpaved streets ("a few times I saw a chicken walking around importantly, like some kind of a regional manager") to a landmark known only as "the nine-story building," where an instructor informed her of the indignities suffered by the Uzbeks at the hands of assorted barbaric conquerors. "Shaking her head sorrowfully, she told me that Genghis Khan not only rode a bull, but he didn't wear any pants. She said that God should forgive her for mentioning such things to me, 'but he didn't wear any pants.'"

The language known as "Old Uzbek," despite its dubious history and the fact that no books printed in it could be found in any of the Samarkand bookstores, was portrayed to Batuman as infinitely more illustrious and refined than Persian. "Old Uzbek had special verbs for being unable to sleep, for speaking while feeding animals, for being a hypocrite, for gazing imploringly into a lover's face, for dispersing a crowd. It was all just like a Borges story -- except that Borges stories are always so short, whereas life in Samarkand kept dragging obscurely on and on." One great Old Uzbek poet, blind from birth, evidenced his talent by "molding a cooked bean into the shape of a ram, an animal he had never seen before." A medieval Uzbek poem takes the form of love letters exchanged between the colors red and green.

Batuman's affinity for the intersection of the grandiose and the absurd led her -- unsurprisingly to anyone but herself -- into an academic career. As a graduate student, she attracted the kind of friend who'd call up for advice on how to deal with dirty underwear, or who came over in the pouring rain to expound on "the two simple keys that were necessary for a perfect understanding of the poet Osip Mandelstam" or who, in one memorable example, wound up joining a monastery on an Adriatic island.

Batuman's various scholarly projects have a sprightly aspect one doesn't ordinarily associate with comp lit departments. They include: a dissertation comparing novel-writing to double-entry bookkeeping, a consideration of the "narrating sidekick" as a literary device (I should add that she seems nearly as obsessed with Sherlock Holmes as with any Russian character) and a contemplation of "the hugeness of novels, the way they devour time and material." In hopes of obtaining a field-research grant to get her to a conference at Tolstoy's former estate, she concocted a theory that the novelist might have been murdered. Then she seems to have half-convinced herself that it might be true. Meanwhile, her beloved Russians continued to provide her with fodder. On the flight over, Aeroflot lost her luggage, and when she called to check on it, she was told it would be sent to her eventually, but "in the meantime, are you familiar with our Russian phrase, resignation of the soul?"

The very funny voice Batuman uses to recount her exploits can be drolly formal, as if all the old books she reads have infected her with the antique air of a provincial czarist official. An incident in which she is bored by a fellow traveler on a layover in the Frankfurt airport is characterized as "having extinguished two hours of my youth." And who under the age of 60 uses the word "comportment"? Or perhaps this is just the way you wind up writing when you're the sort of person who gets dragooned into judging a boys' "leg contest" in a Hungarian summer camp.

Possibly there isn't enough direct discussion of Russian literature in Batuman's book to please those who will pick it up with that expectation. Even the chapter devoted to the Dostoevsky novel that gives the book its title (relating "the descent into madness of a circle of intellectuals in a remote Russian village") spends most of its pages detailing how disturbingly her friends in graduate school replicated the same story. (The current, more accurate translation of Dostoevsky's title for that book is "The Demons.") Perhaps it's all just another mystification. Regardless, I'm hooked.

Shares