For veterans of the Web browser wars of 1990s the news that J Allard is "retiring" from Microsoft shocks the brain like a bite into Proust's madeleine. Suddenly I can taste the flavor of Netscape 1.0 downloading over a 14.4 baud modem all over again, thrill to the frisson of my first flame-war, shudder with that calm arrogance of knowing that the world has changed forever.

J Allard was the guy who got the Internet at Microsoft; his infamous January 1994 memo "Windows -- the Next Killer App for the Internet," made an undeniable business case requiring Microsoft to get serious about the Net. What happened next was a remarkable display of nimble corporate reorientation. Microsoft was caught flat-footed by the cyberspace explosion, but once Bill Gates and Co. decided to focus, the company was unstoppable. Microsoft blasted Netscape out of the dot-com water, and entrenched itself everywhere on the Web. Resistance was futile.

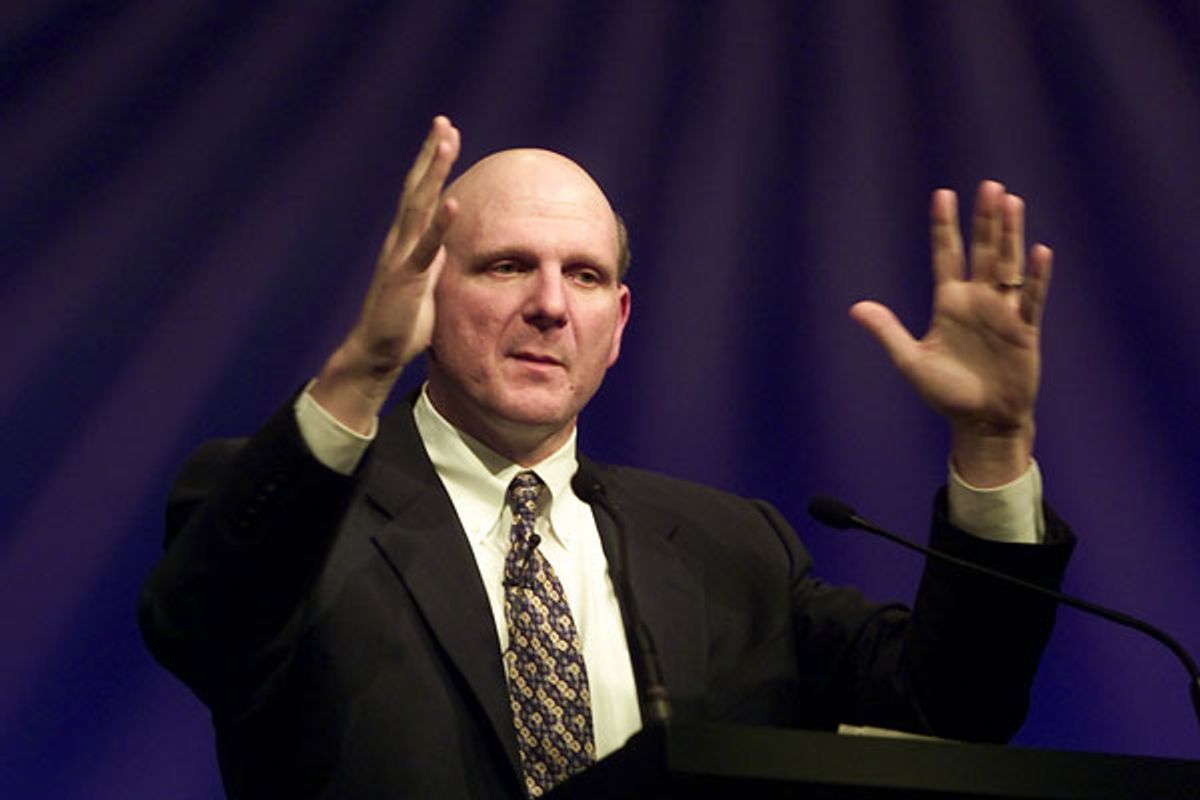

Which is exactly what makes Allard's departure so poignant, (or if that word seems out of place in a Microsoftian context, try ironic, or karma-fantastic). Because there's little question why Allard and Robbie Bach, the two executives in charge of Microsoft's entertainment and devices division are being forced out of their jobs by CEO Steve Ballmer. They're the fall guys for Microsoft's abject failure to be relevant to the next frontier of digital life. Microsoft got the Net, but then, somehow, it lost it. It's Google versus Apple now, with Microsoft an afterthought.

There's no reason to shed tears for Allard or Bach. They had good runs and are undoubtedly financially set for life. But somehow, it seems like the guy at the top should be shouldering a little more of the blame.

Let's outsource to The Baseline Scenario's James Kwak:

Steve Ballmer has been CEO of Microsoft since 2000. During his tenure, Microsoft came out with Windows Vista, perhaps the most unsuccessful operating system in modern history (Windows ME doesn't count, since Microsoft's core customer base was using NT/2000); it tried a "Microsoft inside" strategy in digital music and, when that failed, launched the Zune, which also failed; it watched Firefox (and Safari and Chrome) eat a large chunk of its lunch in Internet browsers, the application most people use more than everything else put together; it launched Windows Live, a marketing strategy with no noun behind it, which completely flopped at whatever it was supposed to do; it got blown away in Internet search to the point where it had to re-launch as Bing, a plucky underdog; and in mobile phones, which everyone has known for a decade would be the next big thing, it stuck with its bloated, awkward Windows Mobile for far too long, letting everyone (RIM, Apple, Google, and even Palm) pass it by to the point where it has no customer base left. (BlackBerry rules the corporate market, Microsoft's traditional stomping grounds.) Recently I saw a headline saying that Microsoft is going to try to relaunch Hotmail to make it cool. Really, why bother?

How did this happen?

The answer is complicated, a mix of multiple factors, including executive mis-steps at Microsoft and a mass migration of top computing talent to companies like Google and Apple. Microsoft was never exactly "cool" -- but for a time it definitely ruled the roost and could skim off the cream of the job applicant pool. That is no longer true.

On the modern Internet, where day by day, cloud-based computing becomes ever more indistinguishable from chained-to-the-desktop software, it's also clearly harder for Microsoft to leverage its near monopoly-share of the operating system market.

Microsoft was also always convinced that by brute force it could tackle and take over any market, no matter how clunky its initial offerings. The company made a fine art of gradually, relentlessly improving its products, copying whatever anyone else had done, embracing and extending and incrementally tweaking. The first Internet Explorer browser was ludicrously bad. And then a year or two later, it could do everything Netscape could do and more. But that kind of constant incremental improvement business model is now part of every successful tech company's DNA. Google and Apple aren't waiting around for Microsoft to catch up -- it's full speed ahead, or die, for the entire industry.

Rereading Allard's essay offers other clues. There's no question Allard understood what he was looking at, the amazing potential of the Internet as an access-point for information, the commercial possibilities, even the inevitable culture-clash between the natives of the open Net and the Microsofties. I can't fault any of his analysis, or his conviction. But the pitch to the Microsoft brass is primarily framed in terms of how Microsoft should be able to co-opt the Internet to serve its corporate interests. I'm sure that was by necessity, but it offers a hint as to why Microsoft eventually lost its way. Allard's tone is: Here's this important thing that we need to exploit, instead of, here is this incredibly cool thing that enables people to do all kinds of cool things: how can we be cool like that?

Allard's focus: The Internet is an important way for us to make money. Apple and Google's focus: How do we make the Internet work for you. Their philosophies are different -- Apple believes in controlling the interface, while Google pursues a more open approach -- but the fundamental understanding is shared. Cool tools to do cool things. Meanwhile, Microsoft just wants market share.

Microsoft, despite J Allard's best efforts, never went native, never really figured out how be part of the culture, instead of a carpet-bagging interloper. Apple was always there, even before the Net, lost its way, and then found it again. Google was born there and never left.

Microsoft has surprised us before, so maybe Ballmer can do it again. But this corporate shakeup doesn't feel like a swift, opportunistic change of direction. It feels desperate; an admission of failure instead of a cagy commitment to seize the day.

Shares