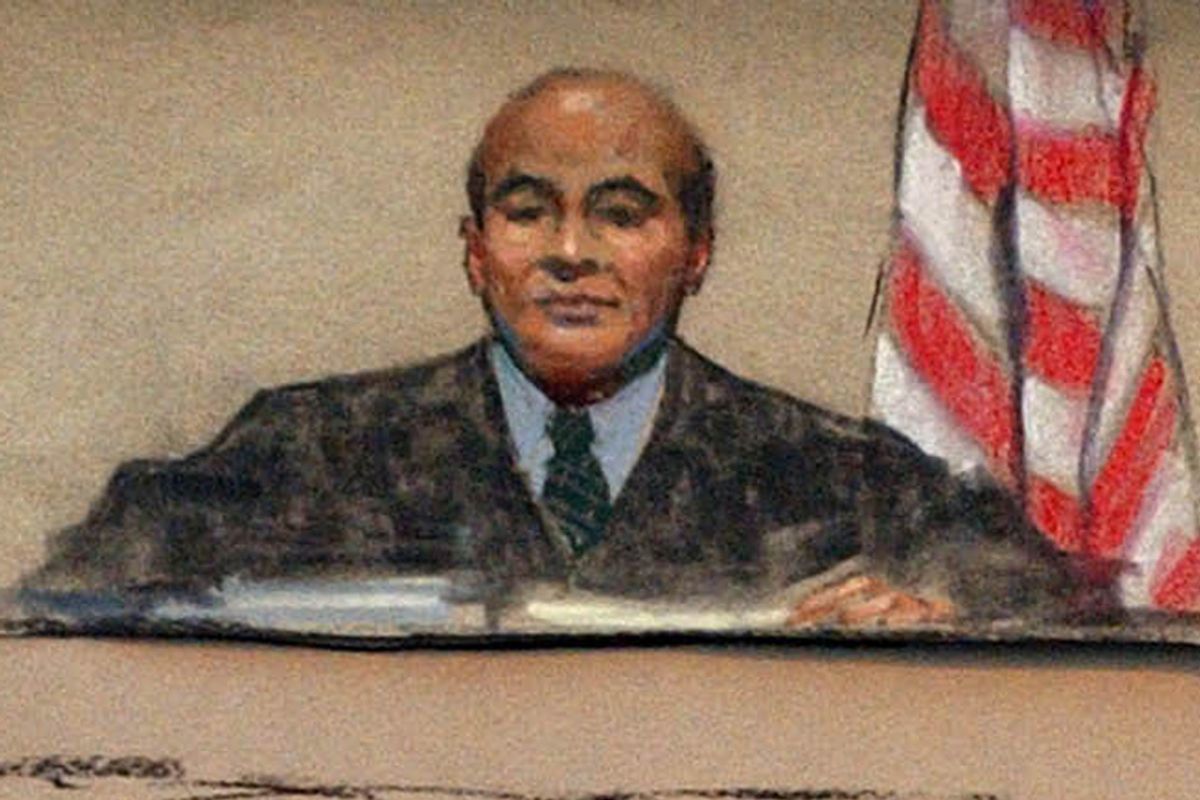

Nothing in the reaction to his landmark ruling against the Defense of Marriage Act is likely to have surprised Judge Joseph L. Tauro, from controversies over his reasoning to criticisms of him personally. When commentators mention that he is a "79-year-old Nixon appointee," that is no doubt meant to signify the supposed conservatism of a judge who is, indeed, a lifelong Republican. When others acidly refer to the obvious fact that he's from Massachusetts, that is surely meant to flag a "flaming liberal" who always yearned to validate same-sex marital rights.

And when the executive director of the Traditional Values Coalition spits phrases like "rogue judge" and "judicial activist," she plainly is questioning the legitimacy not only of his decision but of his position.

During nearly four decades on the federal bench, Joe Tauro has repeatedly proved that agitated rhetoric doesn't impress him. Years ago, I profiled Tauro for a Boston-area weekly newspaper, and what I learned about him back then seems just as true today. Neither partisan nor ideological, he is a pragmatic figure who believes his job is to apply the Constitution and the law in defense of basic human rights. Lawyers can and will argue, with the best and worst of intentions, over his citations of the 10th and 14th Amendments in the decisions that struck down parts of DOMA. Will his interpretation of equal protection stand on appeal (if it is appealed)? Was his appeal to states' rights mischievous, in every sense of the word? Are his arguments regarding federal preemption contradictory?

Perhaps Tauro's decision eventually will be overturned on any or all of those grounds. Meanwhile his critics have depicted him as merely another remote, black-robed elitist, dictating social policy from the courthouse, without sufficient attention to political realities and public opinion. But this is a jurist whose most important legacy -- until now, at least -- was the complete reconstruction of his state's institutions for the care of the mentally disabled. In 1973, not long after ascending to the bench, he declared their disgraceful, hideous and inhumane practices unconstitutional. His mission to reform them began with a class action brought by the father of a resident of the infamous Belchertown School for the Feeble-Minded.

Not long after he received the case, Tauro visited the Belchertown premises -- whereupon he persuaded the state attorney general and other officials to enter into a consent decree rather than attempt to defend the indefensible. The complaints of the Belchertown families were true, he said. The only purpose of any further discussion should be to remedy them.

If that was radical, in the best sense, then his eventual assertion of control over the state's entire system was even more so. Over the 15 years or so that followed, he oversaw substantial increases in budgets and staffing that led to enormous improvement in those institutions and the lives of the mentally disabled -- and national recognition that neglect and mistreatment of the defenseless were no longer tolerable.

Needless to say, some politicians on Beacon Hill didn't appreciate a federal judge issuing orders on state spending or placing a special master in charge of state agencies. But Tauro, who had previously served as a top aide to a Republican governor and then as U.S. attorney, managed those delicate relationships with great skill. Rather than simply hand down decrees from the bench, he understood where and how to apply pressure, whose arms to twist quietly, who should get a phone call, and when to call everyone into his chambers for a friendly chat.

After his first visit to Belchertown, he also realized that his effort would be far more likely to succeed if everyone else saw what had distressed him so deeply. He began making repeated visits to the so-called schools, bringing journalists, legislators and state officials with him on chartered buses for "tours" of the state's dilapidated, filthy and understaffed facilities.

Surely he regarded those hellholes as a violation of constitutional justice -- and just as surely he seized the chance to improve the lives of the men, women and children oppressed in those places. The same may well be true of his motivation in the DOMA case, where he saw a blatant offense against equality but also a chance to relieve the suffering of decent, hardworking people like Herb Burtis -- the same age as the judge, impoverished but ineligible for $700 in monthly Social Security survivor benefits after living for 60 years with John Ferris, his late male companion.

Does that make Tauro a "judicial activist"? As he once said regarding the Belchertown class action, "We don't go out looking for cases ... There is no such thing as an 'activist court.' I do nothing until a complaint has been filed by some citizen, or group of citizens, which states effectively that their constitutional rights have been violated. I then have an obligation; I can't just dismiss it and throw it away."

Shares