I've only once woken up screaming. It was because I'd seen a ghost.

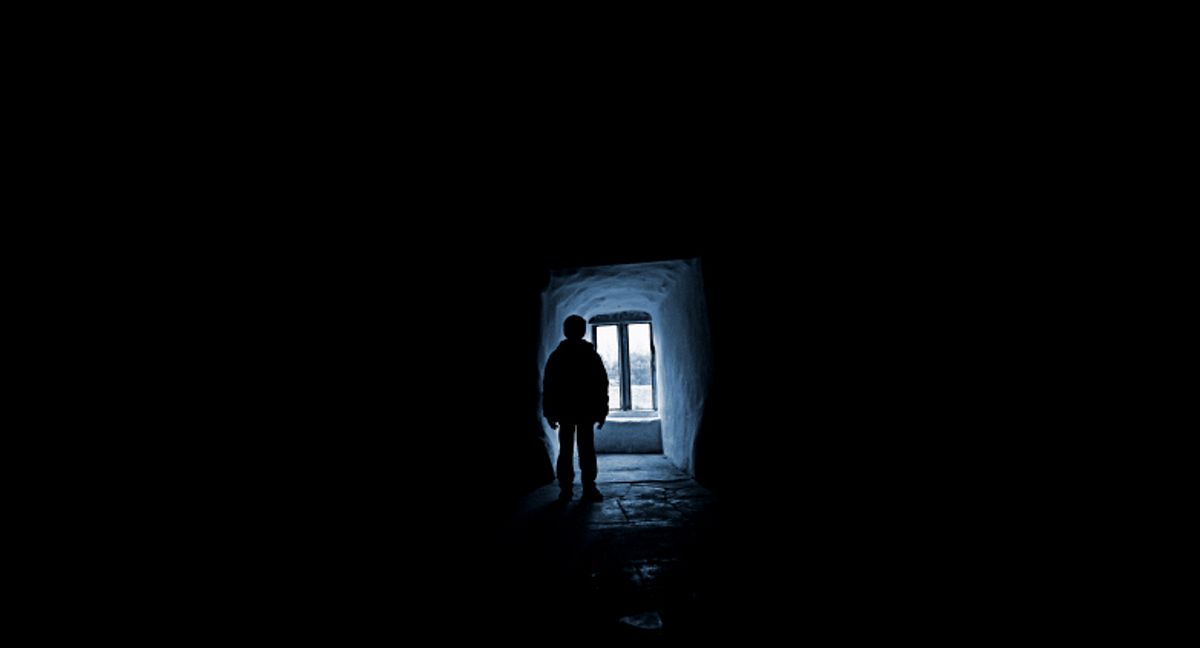

About 10 years ago, I was lying in the bedroom of my house in Cheyenne, Wyo., an old place that used to be workmen's lodging down by the Union Pacific railroad station. I wasn't in a deep sleep, more like that murky in-between state as slumber comes in for a landing. I opened my eyes halfway. In the doorway of the bedroom, a young man stood staring at me. Was he 15? Was he 20? Dressed in work clothes from the 1930s, of humble posture, he was there -- I will never forget those eyes -- yet I could see straight through him. Frightened to my core, I sat up, screaming until my boyfriend shook me. "What? What?"

"There was a boy over there! He was standing right there."

"No one else is here but us," he told me. "You were dreaming."

But I wasn't. The shock and fear left me shaking, but most disturbing was the physical sensation. I hadn't just seen this ghost boy; I had felt him. Sorrow, loss, loneliness. It was as if he was saying, I'm lost. Help me. I need to be seen.

I kept the bathroom light on all night for a month, maybe more, my eyes trained on that doorway. If I was going up the stairs in the dark, I would climb quickly, two steps at a time, as if someone, or something, was chasing me.

Growing up, a gory Halloween costume or haunted house could scare the daylights out of me, but I'd always been skeptical about ghosts and spirits. When I was 20, a hardened realist -- and an atheist, to boot -- broadened my mind. At the epicenter of the Bay Area punk scene in the '80s and '90s was a guy named Tim Yohannon. A product of the '60s counterculture's angry edge, he was punk rock's own paterfamilias, a graying, squatty Azerbaijani Humphrey Bogart. He taunted vegetarians. He smoked about 8,000 Benson and Hedges a day. Like much of my peace-punk cohort, I loved and looked up to Tim. He was generous, and in the midst of the crazy punk scene, he radiated sanity. Once, when we were driving along a winding Marin County road on the way back from a day at Stinson Beach, our hair sticky with sea salt, he told me that once, when staying at a nearby bed and breakfast, he'd seen a ghost. He was jolted awake by a strange voice hissing "TIM!" He opened his eyes to see a mean-looking disembodied head, floating there. He and his girlfriend dropped the key at the front desk and fled. I thought, if a realist -- a non-believer no less -- could encounter the supernatural, then maybe there was something to it.

In 1998, Tim died after a lengthy battle with lymphoma. While it is painful to lose a friend in any capacity, the loss of a role model is particularly acute. A sharp pain as the light draws down on a certain phase of your life -- the end of an era, indeed. But slowly, he faded from memory, supplanted by more immediate losses -- my father, a grandmother. Then last year, I went through a bout of insomnia. Work, as usual, was keeping me up at night, worse than ever.

As I stared at the laptop screen, the glow of the blank page insulting my eyes, I kept hearing Tim's voice in my head: "Be punk rock about it!" It bedeviled me. Not the sentiment; I got what it meant: Be bold. Leave a blistering mark. But the voice's persistence. Why now? I hadn't thought about him in, honestly, years. Yet, if the voice in my head was to be believed, it was as if he never left. Fully inhabited by the idea of him, I went downstairs to the kitchen for a drink of water. Then I drifted to the back door and opened it. I stood on the creaking old wood porch, dry-rotted wood on the door sill flaking under my feet, and tilted back my chin. The night was perfectly clear, no moon, the October air acutely sharp.

I looked up into the center of the starry sky and held out my arms, "OK, fine, Tim. If you're really there, then prove it." At that moment, a small but brilliant meteor streaked brightly across midheaven. The hairs at the base of my neck got all tickly and tears sprung up in my eyes. I felt as if I'd risen from my body, weightless. My breath whooshed out of me. "Cool," I said, to no one.

Lit up inside, I went back into the house, and powered through my assignment. There was something inspiring about what seemed like a paranormal visitation from an avowed atheist. Maybe it was his way of saying, "Hey, I was wrong. There's more." And a command performance in the sky: There was a wit to it. I know some people will insist that meteor was a coincidence, but I insist that it wasn't. And unlike my first brush with the Otherworld, I felt no fear whatsoever. Though the living Tim would have hated this particular expression, I felt blessed.

I've shared these experiences with people from time to time, and I've found that by admitting supernatural experience, a floodgate opens: A friend who swears he smells his grandfather's pipe whenever he's in danger -- a car about to serve in front of his bike, a branch overhead threatening to break, when he's hiking alone. A widow who is sure her husband tells her where she's put misplaced objects. These stories are often shared in the dead of night, when conversation veers off-grid, toward the realm of the unexpected. Maybe such topics are more welcome in the safety of darkness. I am only too happy to miss sleep to hear them. We're so rarely invited into each other's interior lives, and if you tell me that a departed loved one makes his or her presence known, I don't think you're crazy. I think you're lucky.

Do ghosts and spirits really exist? Sometimes, I still take that question into my backyard. With the fragile faith of the near-converted, I stare at the night sky, waiting, thinking about the ghosts in my life. How much of their vaporous presence is genuine, and how much is a trick of the mind, a fondest wish or worst fear manifest? It's hard to say. While I'm far from a state of certainty, there are a couple of things I believe in my heart: that there are more possibilities out there than we could ever fully imagine. And I'm no longer afraid of the dark.

Lily Burana is the author of three books, most recently "I Love a Man in Uniform: A Memoir of Love, War, and Other Battles."

Shares