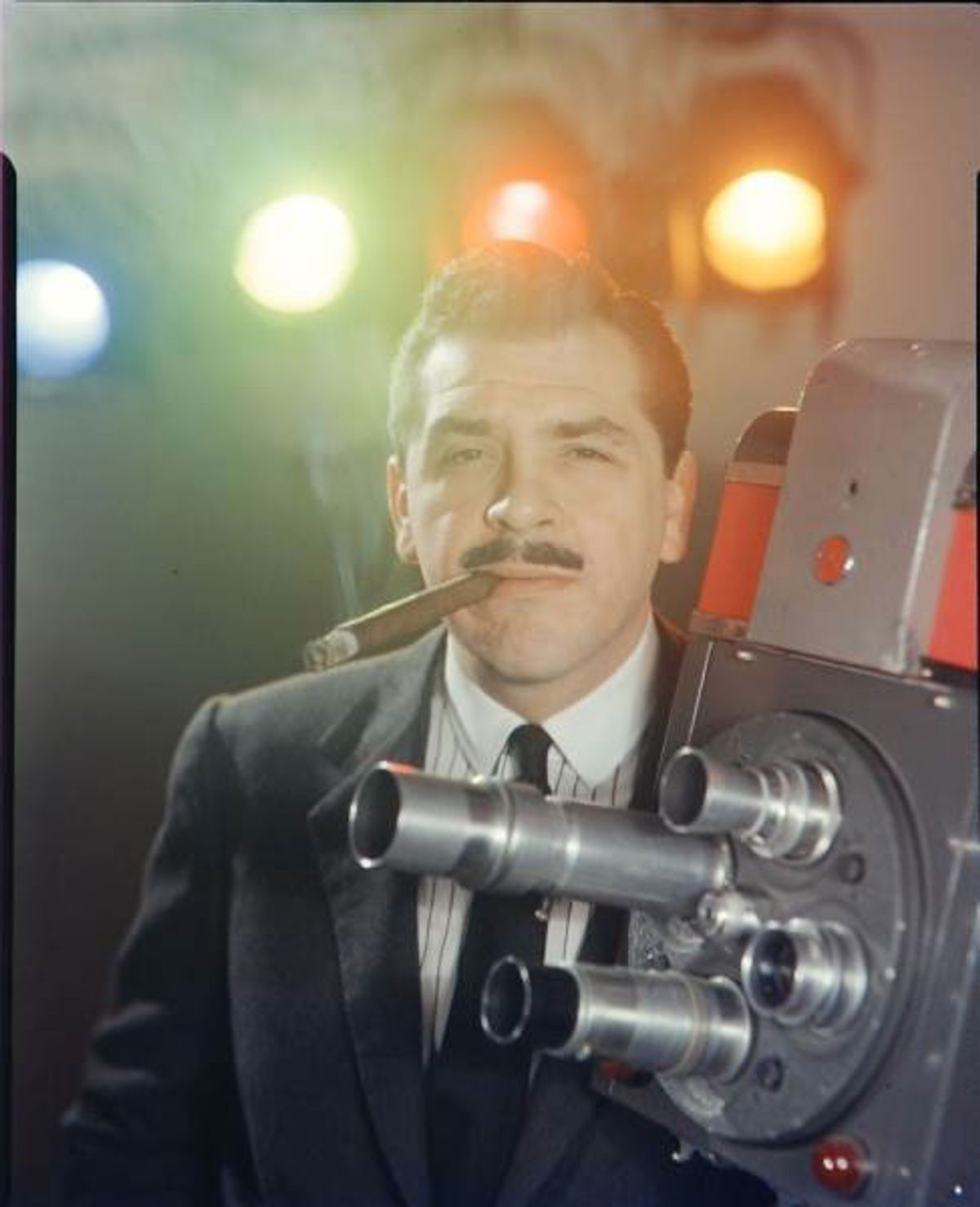

Was television made for Ernie Kovacs, or was Ernie Kovacs made for television? No matter; when you picture his face, you envision a 4x3 frame around it. And it's never quite in focus; it's blurry, smeared at times -- a kinescope record of his kaleidoscope mind.

Kovacs' art -- which is collected in a marvelous new DVD set titled "The Ernie Kovacs Collection" -- was more original, personal and bizarre than anything else being done in the early days of television. At a time when the medium was still figuring out what it was -- and modeling itself alternately on radio, cinema, legit theater, and vaudeville -- the Trenton, N.J. native decided to wing it and see what happened. He treated the TV studio as a playground and the camera as his playmate. At the heart of everything he did was a simple realization: the television camera is not a recording device, but an expressive tool -- a machine that transforms the real into the virtual, and makes even the weirdest flights of fancy seem natural.

Some of TV's most innovative people and programs drew inspiration from Kovacs: Rowan and Martin, the Smothers Brothers, Monty Python, Kids in the Hall, SCTV, the "Saturday Night Live" casts, every host of NBC's "Tonight Show," and all the talk shows modeled on "Tonight." Morning shows raided him, too: Kovacs' 1951 program "Three to Get Ready," broadcast live on Philadelphia's WPTV, was the first morning program anywhere, and was supposedly the inspiration for NBC's "Today."

That signature move of David Letterman's -- suddenly "realizing" mid-joke that a camera is observing him, then slowly walking toward it and pressing his mug right up into the lens -- is an homage to Kovacs. Ditto the Letterman and post-Letterman practice of demystifying the TV studio and inviting the viewer to see it as a grubby workspace with green rooms, control rooms, long corridors, administrative offices, and armies of personnel laboring behind-the-scenes and emphasizing the fragility of the whole enterprise by botching a camera move, missing a cue, or tripping up the host with an illegible cue card or lame joke. There's an entire subgenre of TV comedy -- typified by Letterman, Conan O'Brien, Jimmy Kimmel, Craig Ferguson, and other students of TV's first Golden Age -- that could be called, for lack of a better word, Kovacsian. It cultivates chaos and goes looking for accidents.

Kovacs loved to pull the rug out from under the viewer by promising one thing and delivering something else. There's a moment in a July 2, 1956 episode of Kovacs' NBC evening show (included in the DVD set) where Kovacs, playing the lisping, bespectacled, frog-eyed poet Percy Dovetonsils, pauses in the middle of one of his trademark nonsensical poems ("Thoughts While Falling Off the Empire State Building") to notice a couple of stagehands bringing a horse onstage in preparation for the next sketch. Percy is so nonplussed that he aborts his own performance. What's truly inspired about this moment (beyond Kovacs' comic acting chops) is that once you've watched a bit of Kovacs and gotten used to his methods, you wonder if the "interruption" is spontaneous or planned. Just as Kovacs blurred the boundaries between every medium that came before TV, he also blurred the line between ad libs and scripted material -- between the "real" and the "fake."

Look what Kovacs does with this seemingly unremarkable "Host wanders into the stands and banters with the audience" bit. He sets you up for a card trick that he never actually performs. Then, on discovering that his target is an engraver who called in sick to work so that he could attend the broadcast, he commiserates with the man over getting busted. "You been working there long?" Kovacs asks. "Oh, about two or three years," the man replies. "Well, I'm sure there's a vacancy for an engraver out there somewhere," Kovacs says, then gives him his prize: the address of the Acme Employment Agency.

You expect the unexpected from Kovacs. Sometimes it arrives in the form of ad-libs or out-of-nowhere shtick. Other times Kovacs makes you think he's being spontaneous when in fact the veneer of "spontaneity" is setting up a gag that took a long time to plan. He might interrupt a monologue to go wandering around backstage, and invite the camera to follow him -- an "improvisation" that had to have been carefully mapped out, considering the hugeness of 1950s TV cameras. Or he might "kill time" at the end of a broadcast by whipping out a marker and drawing on a large sketchpad, and when he finished, animated characters or words would appear in sections of the drawing, and you'd realize that it wasn't a sketchpad at all, but a disguised scrim onto which pre-made graphics or animation were being projected.

In another Percy Dovetonsils sketch, Percy sits in his throne chair watching a couple make chit-chat on TV set embedded in the wall. Then he stands up, reaches through the screen, deftly grabs the champagne glass out of the man's hand, takes a sip, gives the glass back, and exits the frame with an impish shrug.

Kovacs often worked pre-recorded or partly pre-recorded bits into his broadcasts that showcased elaborately choreographed live performances, puppetry, mime, animation, shadowplay or painting-with-light. Some bits were synced to music so precisely that certain pop historians consider Kovacs the father of the music video -- although that description doesn't do justice to gems such as The Nairoibi Trio or the bit below, "Kitchen Symphony."

As my colleague and fellow Kovacs buff David Kronke observes in the DVD's liner notes, "He mastered blackout sketches, usually a series of visual puns linked together by the song 'Mack the Knife.' Perhaps the most famous of these involved an oil used-car salesman slapping the hood of a sweet ride, the force of his blow sending it collapsing through a breakaway floor. The joke almost seemed to be that Ernie would invest so much effort and money ($12,000) for a six-second gag."

You can't get a read on what's random and what's scripted. Some moments are so bizarre that you can't quite process them -- and Kovacs amps up the strangeness by playing the moment with a straight face. Look at this opening bit included in the DVD set: Kovacs sets up his opening sketch, which supposedly features guests suggested by viewers, while ducking knives tossed by an offstage knife-thrower. Kovacs' on-the-edge-of-anxious reactions and the ferocious timing and velocity of the throws add another wrinkle -- a hint of menace. Are the knife-throws real or faked? Is he in real danger, or is he just a very good actor?

The Shout! Factory set is drawn from the private collection amassed by Kovacs' wife and longtime costar, Edie Adams, who died in 2008. Adams rescued the masters a few years after Kovacs' tragic 1962 death in a car wreck, after learning that network technicians were erasing them so that they could re-use the tapes. (This sounds like an unthinkably barbaric thing to do to archives of TV's early years, but it was unfortunately common in the '60s; a lot of Johnny Carson's pre-1970 work was lost when NBC bulk-erased the masters.)

It's great to be able to see a selection of Kovacs' work, in black-and-white and color, in better quality than has been seen before, over a span of a decade -- not piecemeal, but in context. Whole shows are reproduced so that you can see what worked and what didn't, and sense how Kovacs' deadpan screen persona held these unwieldy contraptions together. You understand why personalities as diverse as Letterman, Chevy Chase, Leno and Kimmel spent so much time scrutinizing and emulating Kovacs. Over and above his formal daring, he was a forward-looking screen performer, several degrees cooler than early TV's vaudeville-derived norm. Intimacy was his watchword. Avoiding large studio audiences whenever he could, Kovacs played to small crowds, often just to his own crew, and pitched everything to the camera, which represented the viewer. This made it seem as though every sketch and moment was aimed at an audience of one.

Shares