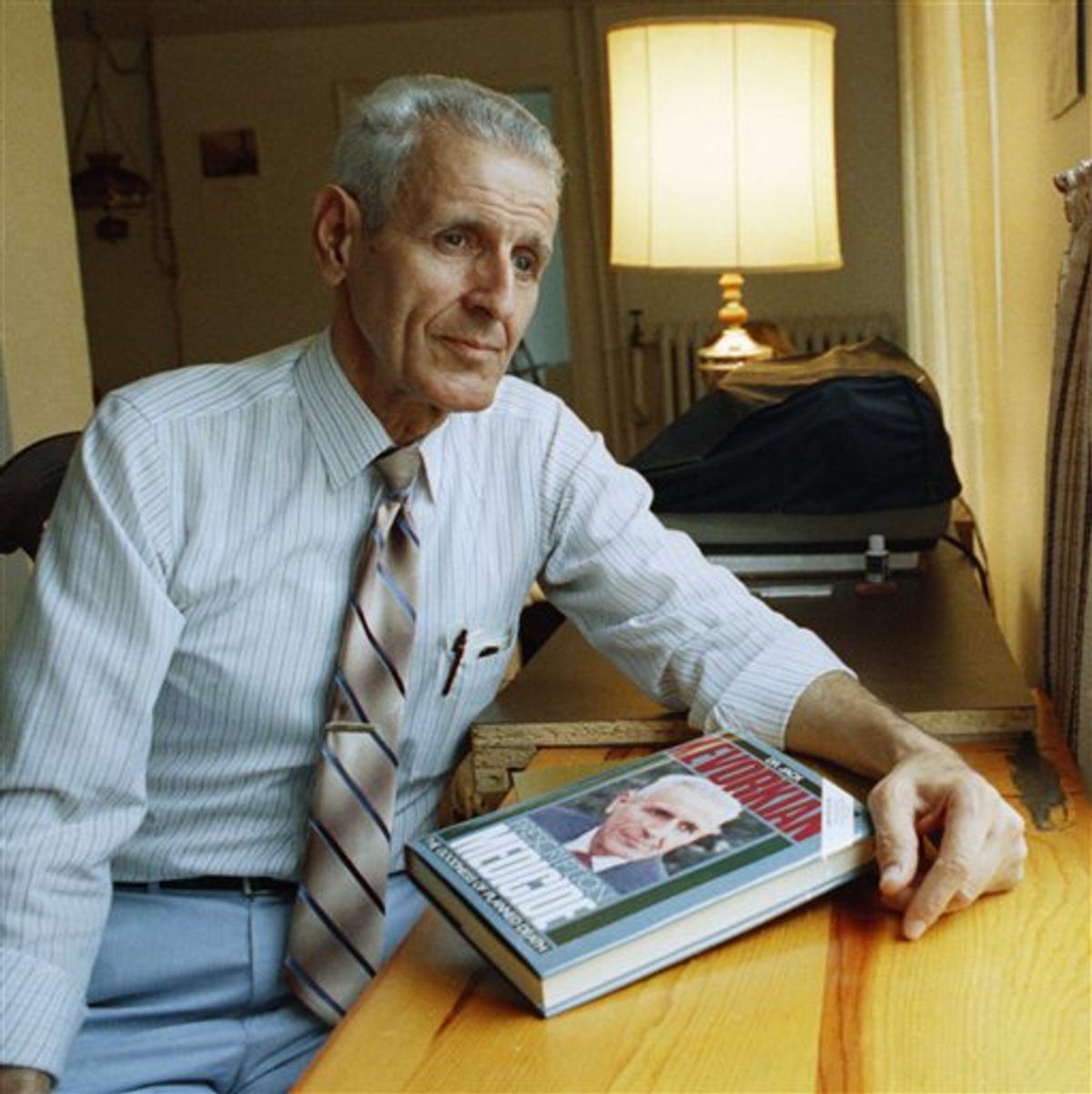

After championing the rights of the sick and suffering to get help ending their lives -- and providing that "help" to scores of terminally ill patients -- Dr. Jack Kevorkian died of natural causes on Friday at the age of 83.

According to Geoffrey Fieger, the lawyer who represented Kevorkian in several of his trials in the 1990s, Kevorkian was too weak to take advantage of the option he had offered others and had long wished for himself. "If he had enough strength to do something about it," Fieger told a news conference in Southfield, Michigan, "he would have."

If that is true, there is something almost epically tragic about the fact that a man who fought so long and hard for patients’ right to die on their own terms, wasn’t able to take advantage of this option in the end. But then who is to say "Dr. Death" didn’t simply change his mind? He’d apparently been suffering from kidney failure and pneumonia for over a month, long enough to plan his own death if he’d wanted to. He was a doctor and entirely familiar with how to end a life quickly and painlessly. And given his well-known penchant for drama and attention, you’d think he’d want to make himself exhibit A for what he believed in. (At the start of his third trial, he showed up in court wearing Colonial-era clothing to show how antiquated he thought the charges were and, after videotaping himself helping to kill a patient, he voluntarily handed the tape over to "60 Minutes.")

The fact that Kevorkian didn’t end his own life is, to me, a potent reminder that our political beliefs are not always in the driver’s seat when it comes to death. Just as one can imagine even the staunchest anti-assisted suicide crusader wavering in the face of extreme pain and disability, I have found that certain pro-assisted suicide people seem to believe that killing oneself is actually a better option than dying naturally. Often, when I mention that I wrote a book about my mother’s decision to end her life after a long illness, people say, "Oh, well I definitely plan to do that. I’ve already made it clear that that the minute I get a disease, I want someone to take me out back and shoot me!"

I get the humor but there is a glib -- even fashionable -- assumption that suicide, assisted or not, is a good way to go. I want to ask: How would your kids feel if you do that? Your spouse? And how would you feel if it was them making that choice? I’m a big supporter of the Death with Dignity Laws in this country, but frankly, as long as I’m not in pain and have some quality of life, I’m planning to "go naturally," just like Kevorkian did in the end.

The idea that ending your life is going to be easier and more straightforward than letting nature take its course is something of a happy illusion. Having witnessed both my parents dying in very different ways, I know that even the best laid plans for death can go awry. It reminds me of the "birth plan" I drafted when I was pregnant. Somehow, between planning the perfect play list and specifying that I didn’t want an episiotomy, I forgot to factor in throwing up, forgetting to breathe, and the uncontrollable urge to yell obscenities at the nurse. So much for my beautiful birthing experience.

It may be a cliche, but there really are some things we can’t control and even for strong-minded people like my mother, who was determined to plot the details of her "end," you simply cannot know how you will feel when the day comes. In fact, my mother set and changed her "death dates" several times, discovering on the chosen day that she wasn’t quite ready to go after all.

In Bill Moyers' PBS special on assisted suicide a few years ago ("On Our Own Terms: Moyers on Dying"), not one of the people Moyers followed actually ended up killing themselves. There was always one more event they wanted to stay alive for: a birthday, or a grandchild’s graduation. Every one of his subjects waited until it was too late and no longer had the physical capability to manage it. All, except for one woman who died from natural causes before she had a chance to take the pills she’d stockpiled. Pulling the plug turns out to not always be so easy.

Adding to the vagaries of the psyche is the unpredictability of the body. Unless you live in one of the three states where physician assisted suicide is legal (Oregon, Washington and Montana) and have access to a group like Compassion & Choices who will help make sure you are taking the right dose of drugs, chances are you will not know how to calibrate the means of death. In my mother’s case, stopping eating and drinking took far longer than she’d expected, and an attempted morphine overdose failed. Although she did ultimately manage to end her life, it was not the controlled, predictable event she’d hoped for.

I read recently that the issue of assisted suicide splits this country almost completely in half, making it an especially divisive and contentious issue. I would respectfully suggest that both sides may have lost sight of the fact that death can – and will -- make a mockery of even the most carefully laid plans, the most passionately held beliefs.

And who knows, when it came down to it, maybe Jack Kevorkian simply wanted to stay alive and was hoping he might recover. Or maybe his lawyer is right and he wished someone had been there to help him speed things along. We will never know and that is as it should be. Because as politicized as it has become in this county, death is ultimately a private experience, fraught with unknowns. And Dr. Kevorkian, like all of us who support assisted suicide as a legal and moral principle, had the right to change his mind.

Zoe FitzGerald Carter is the author of "Imperfect Endings: A Daughter’s Story of Love, Loss, and Letting Go" (Simon & Schuster)

Shares