Oh jeez, do we really have to have to have this argument again? All right, fine. Here goes. Contemporary literature has too much sex and violence, and our kids need to be protected from its "depravity." So says critic Meghan Cox Gurdon, in a scorching Saturday editorial about Young Adult lit for the Wall Street Journal titled "Darkness Too Visible." Let's roll up our sleeves and get to it, shall we?

In it, Gurdon pulls no punches, railing against an "ever-more-appalling" genre in which "kidnapping and pederasty and incest and brutal beatings are now just part of the run of things in novels directed, broadly speaking, at children from the ages of 12 to 18." She writes, with an unapologetic level of disgust, about the "stomach-clenching detail" in modern YA lit, tracing its "no happy ending" roots back to bleak classics like "Go Ask Alice" and "I Am the Cheese," and unfavorably contrasts bestselling author (and darling of the ALA's challenged books list) Lauren Myracle, and her themes of "homophobia, booze and crystal meth" to the glory era of Judy Blume.

Is there really a problem here, besides, perhaps, the offense to Gurdon's sensibilities? The writer laments that while today's crop of trauma lit "may validate the teen experience," she argues that, "it is also possible -- indeed, likely -- that books focusing on pathologies help normalize them and, in the case of self-harm, may even spread their plausibility and likelihood to young people who might otherwise never have imagined such extreme measures." And she argues that "It is a dereliction of duty not to make distinctions in every other aspect of a young person's life between more and less desirable options."

Gurdon is not exactly some pearls-clutching delicate flower, knee-jerkingly opposed to difficult material. She admits that "Reading about homicide doesn't turn a man into a murderer; reading about cheating on exams won't make a kid break the honor code." She lists a few books that she recommends for teens – and they include tough fare like Mark Haddon's "The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time" and Judy Blundell's "What I Saw and How I Lied." She even admits that the sad reality is "many teenagers do not read young-adult books at all." Her limitation is in her argument of what constitutes "desirable options."

As a mother of two voracious readers, one of whom is just shy of the traditional teen lit range, I can certainly vouch that the YA section of your local bookstore can be a pretty damn grim place, rife with everything from angsty vampires to sex abuse to bullying. And no, not all of it is great literature. Remind me again when there was a time when there was nothing but great literature from which to choose? Critics like Gurdon are forever holding the dregs of the present up against the best of the past, which is an unfair and highly loaded argument. You can't compare what's crowding the shelves now with a tiny handful of classics that have endured.

I grew up on Judy Blume too. I also loved V. C. Andrews. Believe me when I say that the latter's books, with their themes of brutal family abuse and incestuous rape, are trashy as hell -- and there was not a girl around for 3,000 miles who could keep her hands off them. And let me further assure you, an entire generation of women managed to devour the "Flowers in the Attic" series without having sex with their brothers. In fact, I can safely say that many of us read "Lace" and Salinger, and Baldwin, and the one didn't rot out the others. We read, as teens continue to do now, to be moved, to fall in love with characters, to learn, and to sometimes just explore the things that scared and fascinated us.

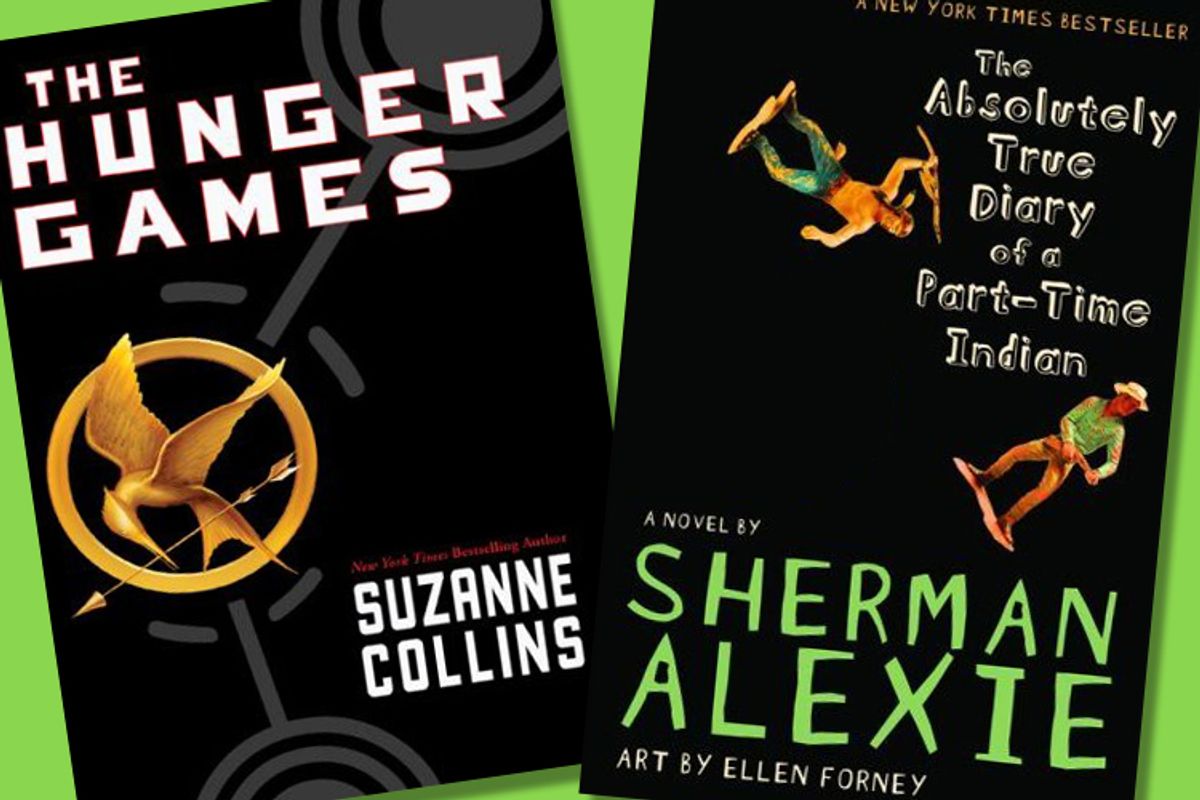

But Gurdon doesn't save her scorn for the merely exploitative, bottom of the rack books. She excoriates the "hyper-violent" "Hunger Games" trilogy and Sherman Alexie's acclaimed "The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian," sniffing that "It is no comment on Mr. Alexie's work to say that one depravity does not justify another." And when she clumsily insists, "publishers use the vehicle of fundamental free-expression principles to try to bulldoze coarseness or misery into … children's lives," she fails to acknowledge the coarseness and misery already inherent in adolescence. She assumes that coarseness and misery -- and profanity, and violence, and sex -- are in and of themselves unsuitable subject matter, regardless of the quality of the writing. That's where she goofs up big time.

I take my kids to the library every week, and I've yet to refuse them anything. Frankly, as a parent I've always been a much bigger hardass about their exposure to the Disney princess-to-sassymouthed teen juggernaut than anything involving abuse or a dystopian future. My elder girl has read the dark "Tillerman Cycle" books, and her class this year read Lois Lowry's frequently challenged "The Giver." And when I asked her what she thought of the WSJ piece this weekend, she rolled her tween eyes and said, "Does she get it that they're not called 'children's' books? They're 'young adult.' Adult."

That "adult" aspect of reading is scary for many of us. It's our job as parents to protect our kids, even as they slowly move out into the world and further away from our dictates. But there's something almost comical about raising them with tales of big bad wolves and poisoned apples, and then deciding at a certain point that literature is too "dark" for them to handle. Kids are smarter than that. And a kid who is lucky enough to give a damn about the value of reading knows the transformative power of books.

One of the terrific side effects of an obviously click-baiting piece of editorial twaddle like Gurdon's is that it reminds people how many fellow passionate readers there are in the world. That incendiary WSJ piece promptly sparked a tear-jerkingly beautiful twitter #YAsaves trend full of heartfelt reactions and links to outstandingly reasoned, article responses from well-read adults and teens on the value within so much of YA literature and its downright lifesaving effects. As teen blogger Emma eloquently explains, "Good literature rips open all the private parts of us -- the parts people like you have deemed too dark, inappropriate, grotesque or abnormal for teens to be feeling -- and then they stitch it all back together again before we even realize they're not talking about us." That's why it matters; why, in the name of protecting teens, we can't shut them off from the outlet of experiencing difficult events and feelings in the relative safety and profound comfort of literature. Darkness isn't the enemy. But ignorance always is.

Shares