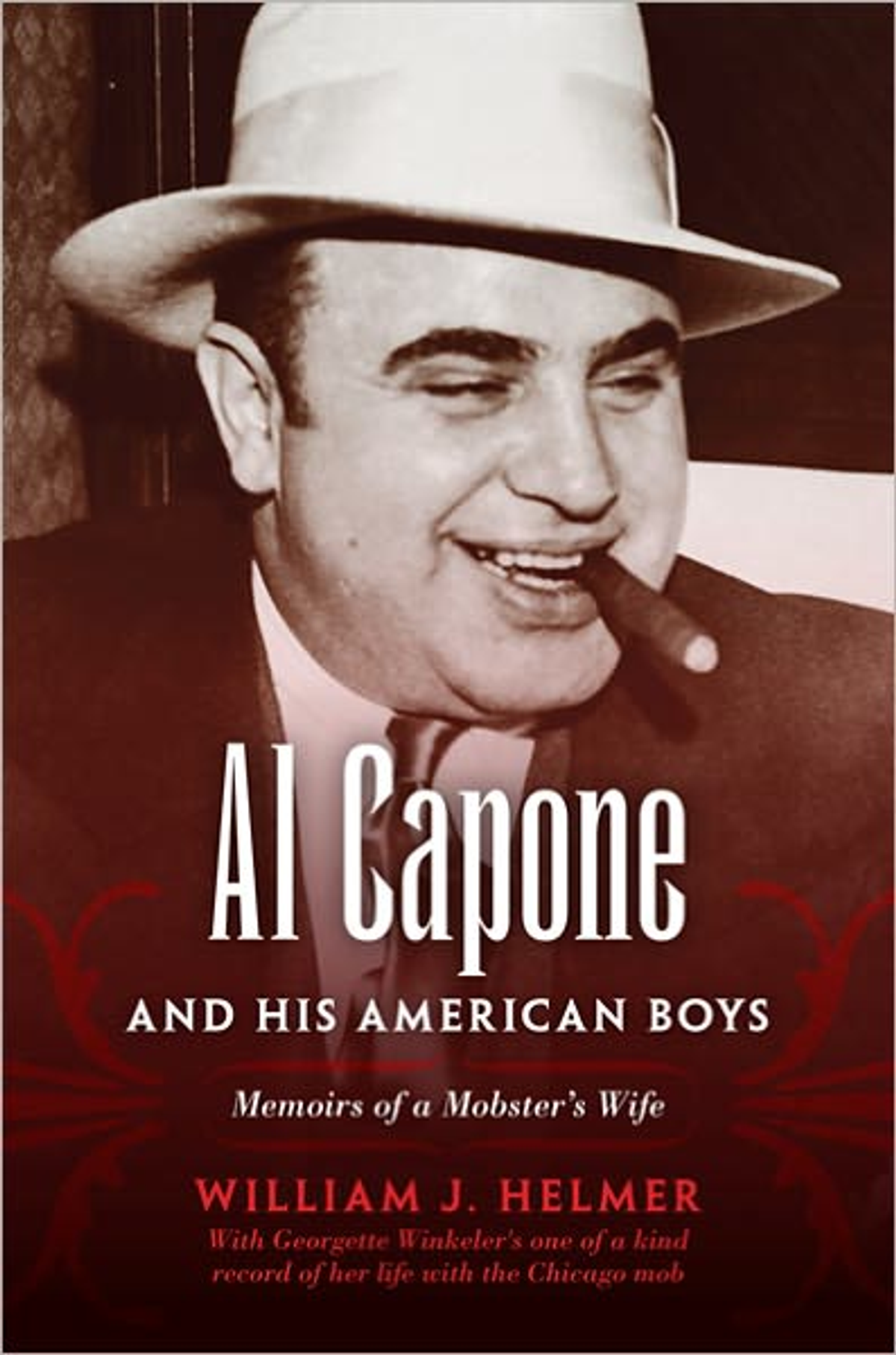

If the gang-moll heroines played by Judy Holliday in "Born Yesterday" and Virginia Mayo in "White Heat" sat down to collaborate on a memoir, the result would read a lot like "Al Capone and His American Boys: Memoirs of a Mobster's Wife." Though you wouldn't necessarily know it from the confusing title and cover, this volume presents the autobiography of Georgette Winkeler, the wife of Gus Winkeler, a leading henchman in Capone's Chicago "Syndicate." In 1934, months after Gus was murdered by his erstwhile colleagues, Georgette decided to write about their life together, hoping to cash in on the public appetite for gangster lore. Her publisher, however, had second thoughts about bringing out a book so full of revelations about the Syndicate -- sensibly enough, given the number of times Georgette herself writes about indiscreet mobsters getting rubbed out. Thwarted, she decided to turn her manuscript, "A Voice From the Grave," over to the FBI, before going on to make a new life for herself as the wife of a preacher. And there it lay for decades, forgotten in the archives, until Mob historian William J. Helmer brought out this edition. (Credited as the author, Helmer really serves as Winkeler's editor.)

If Georgette had published her book in 1934, it really would have made headlines, if only because Gus Winkeler was one of the shooters in the St. Valentine's Day Massacre -- which she calls "a wholesale killing so vicious it shocked the entire nation." Gus was one of the four Capone gunmen who dressed up as cops and tommy-gunned six members of the rival Bugs Moran gang, on Feb. 14, 1929. A few days earlier, Georgette had seen Gus and his pals trying on police uniforms at home; when she went out to buy the newspaper on the afternoon of the 14th and read about the massacre, she knew that Gus had been involved. "When I got to the house," she writes, "I threw the papers in Gus's face and went into my own room. I was too sick with horror to shed tears."

If Georgette had published her book in 1934, it really would have made headlines, if only because Gus Winkeler was one of the shooters in the St. Valentine's Day Massacre -- which she calls "a wholesale killing so vicious it shocked the entire nation." Gus was one of the four Capone gunmen who dressed up as cops and tommy-gunned six members of the rival Bugs Moran gang, on Feb. 14, 1929. A few days earlier, Georgette had seen Gus and his pals trying on police uniforms at home; when she went out to buy the newspaper on the afternoon of the 14th and read about the massacre, she knew that Gus had been involved. "When I got to the house," she writes, "I threw the papers in Gus's face and went into my own room. I was too sick with horror to shed tears."

This is one of many, many moments when Georgette can be seen trying to have her cake and eat it, too: that is, to give the reader the violent inside dope about the Syndicate while making herself sound like a genteel bystander innocently caught up in the mayhem. This is cynical, but it is so naively, unself-consciously cynical that "A Voice From the Grave" often makes you laugh out loud. If Georgette had been invented by, say, Damon Runyon, she would be a great comic creation.

Take the moment when, after chronicling a string of her husband's assassinations, kidnappings and bank robberies, she writes: "When I was well enough to travel we went back to Chicago, and Gus promised he would grant my oft-repeated request that I be allowed to keep house. We had been jumping from one furnished flat to another, with a sprinkling of hotel rooms thrown in between. This had been far from satisfactory to me. I wanted a secluded little place where we were not likely to be bothered and where I could entertain a few friends." Her very diction strains foolishly after gentility; there's nothing Georgette wants more than to have a "nice" place and "nice" friends.

Unfortunately, Gus -- who was passed out drunk in a rooming house bathtub when she first laid eyes on him -- tended to associate with people nicknamed Cokie and Snorting Whitey and Paul Revere (because he was always warning people that the cops were coming). It all sounds very Hollywood -- someone actually says, "Fade, gang, it's the bulls" -- but apparently the great gangster movies of the 1930s were practically documentaries. Just about everything that happens in "Little Caesar" or "The Roaring Twenties" also happened to Gus and Georgette -- right down to the unhappy ending.

Shares