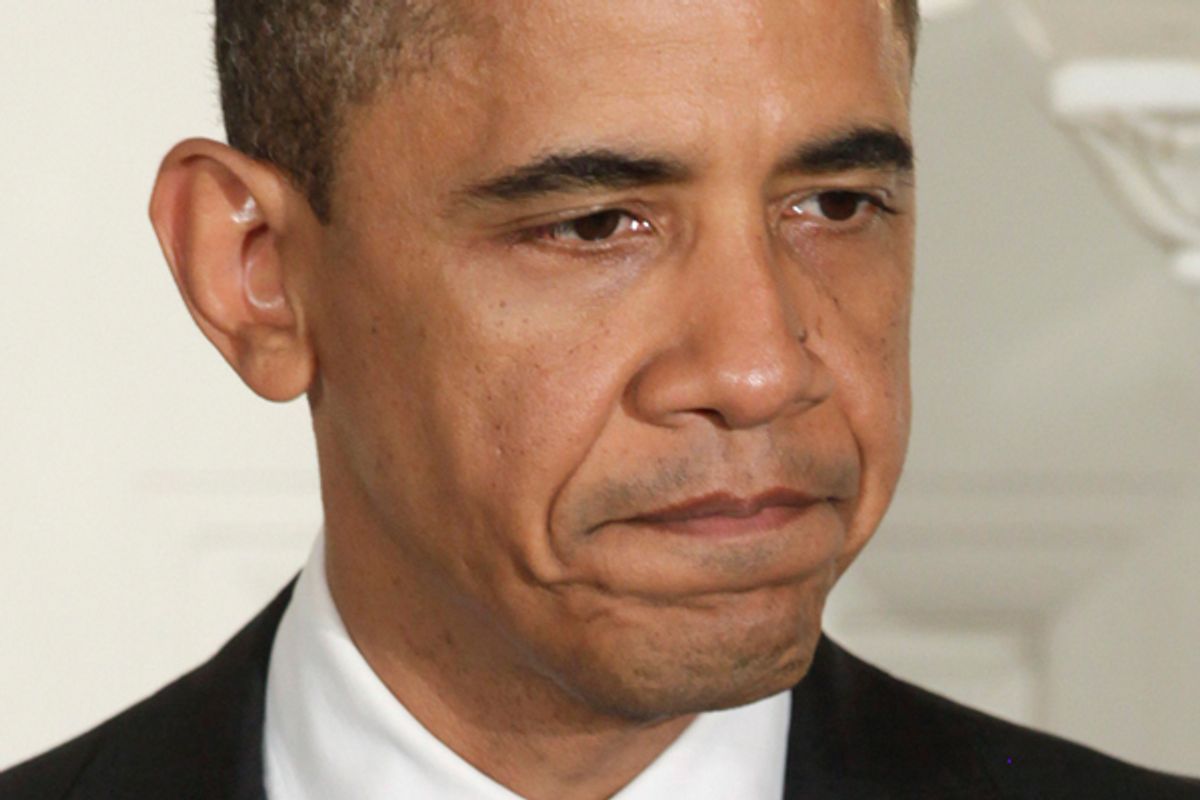

You may have seen a recent cartoon from vastleft.com that went viral, that takes to task liberals who say that Barack Obama's influence is limited ... but that electing Michele Bachmann would be a disaster. I think it does a great job of encapsulating a frustration that's very real among many liberal -- a frustration that's often expressed as anger at Obama by a relatively small group, but I suspect is shared even by the vast majority of liberals who still approve of Obama's performance in office.

The frustration is very real. But the answer implied by the cartoon and embraced by some, the idea that Obama is ultimately responsible for either every outcome or none, is wrong.

If you understand the American political system, you realize two things about this. One is that the president of the United States is, by a fair amount, the most influential person within the system, so it really does matter quite a bit who is president. But at the same time, the president is under enormous constraints and his influence has substantial, and important, limits because there are lots and lots of other people who are empowered by the system -- members of Congress, Cabinet secretaries and mid- and low-level bureaucrats, judges, interest group leaders, party actors, governors and other state and local government officials, the press and more.

Moreover, the positions of the president and most everyone else are, to look at it one way, sort of opposites. The president has potential influence over an astonishing number of things -- not only every single policy of the U.S. government, but policy by state and local governments, foreign governments, and actions of private citizens and groups. Most other political actors have influence over a very narrow range of stuff.

What that means is that while the president's overall influence is certainly far greater than that of a House subcommittee chair or a midlevel civil servant in some agency, his influence over any specific policy may well not be greater than that of such a no-name nobody. A lot of good presidential skills have to do with figuring out how to leverage that overall influence into victories in specific battles, and if we look at presidential history, there are lots of records of successes and failures. In other words, it's hard. It involves difficult choices -- not (primarily) policy choices, but choices in which policies to fight for and which not to, and when and where and how to use the various bargaining chips that are available.

That doesn't mean that presidents are never at fault for anything! Of course presidents are important.

For liberals, a President Bachmann would indeed be a disaster (although I can guarantee that a Bachmann presidency would also produce plenty of frustrated conservatives, just as the Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush presidencies did). And it's not just because of every partisan's trump card, Supreme Court nominations, although they certainly are important. There really are hundreds of smaller-scale policies that presidents can influence. Just from the last month, consider one set of regulations that would require health insurers to cover contraceptives, and another radically increasing mileage in automobiles and, for the first time, trucks. The key is that presidents can influence, but not dictate, those outcomes.

All of which means that if there's an outcome that you don't like, assuming that the president intended it is a mistake. Instead, you have to look carefully at the particular policy domain, and the particular political context, of the president's specific actions. And you should, in my view, have respect for the complexity of the office and the choices involved. And you should understand that presidents choose all the time to cloak their decisions in whatever rhetoric seems popular -- but that there may not be any relationship between the rhetoric the president uses and the basis for decisions.

Wait a second, you might be wondering: Why should I care about any of this?

If you're an activist interested in effecting policy change, it certainly matters quite a bit where you should devote your own limited resources, and if they are to be effective your choices should be based on a good understanding of the system you're trying to affect. If you're disappointed from the left in outcomes during Barack Obama's time in the White House, is it best to support a primary challenge to Obama? To support a third-party candidate? To work even harder for Obama? To give up entirely? To support Democrats in congressional elections? To seek out primary challenges to House and Senate Democrats? To focus one's energies on state and local elections? To ignore candidates entirely, but to focus on interest groups?

To be an effective activist, one must answer those questions as accurately as possible -- and there's simply no way to do so if you believe in fairy tales about the presidency, such as the idea that all policy outcomes should be attributed to the preferences of the man in the Oval Office.

Again, this certainly, absolutely, doesn't mean that presidents shouldn't be criticized; it just means that it's not at all unusual for people to attribute outcomes to presidents that more properly were the responsibility of some no-name bureaucrat or House subcommittee chair. Understanding those realities isn't a way of excusing the president; it's a way of figuring out the best way of fighting for one's preferences.

It's also the best way to appreciate the nature of the U.S. radical experiment in democracy. Partisans and advocates who do realize the complex nature of the system can become frustrated with all the veto points inherent in Madisonian democracy. But turn it around, and realize that each of those veto points is also a meaningful initiation point, and that they are forms of representation, ways of involving more and more people in democratic governance. All this complexity is exactly how Americans fulfill the "by the people" portion of Lincoln's famous formula.

It does mean that the hope for the election that finally settles everything and gets you everything you want is a mirage. And understanding this means giving up the comfort of having a villain who is "in charge" of the country and therefore is the one to blame when things go wrong -- even as it also means doing the hard work of figuring out just who is responsible for mistakes and wrong choices. And, yes, sometimes it will be the president, enough of the time that presidential elections certainly are very important. But if you look closely, you'll often find someone else contributing, and often making far more of a difference.

Shares