It wasn't Bob Dylan. And once again, the Nobel academy did not give its literature prize to an American.

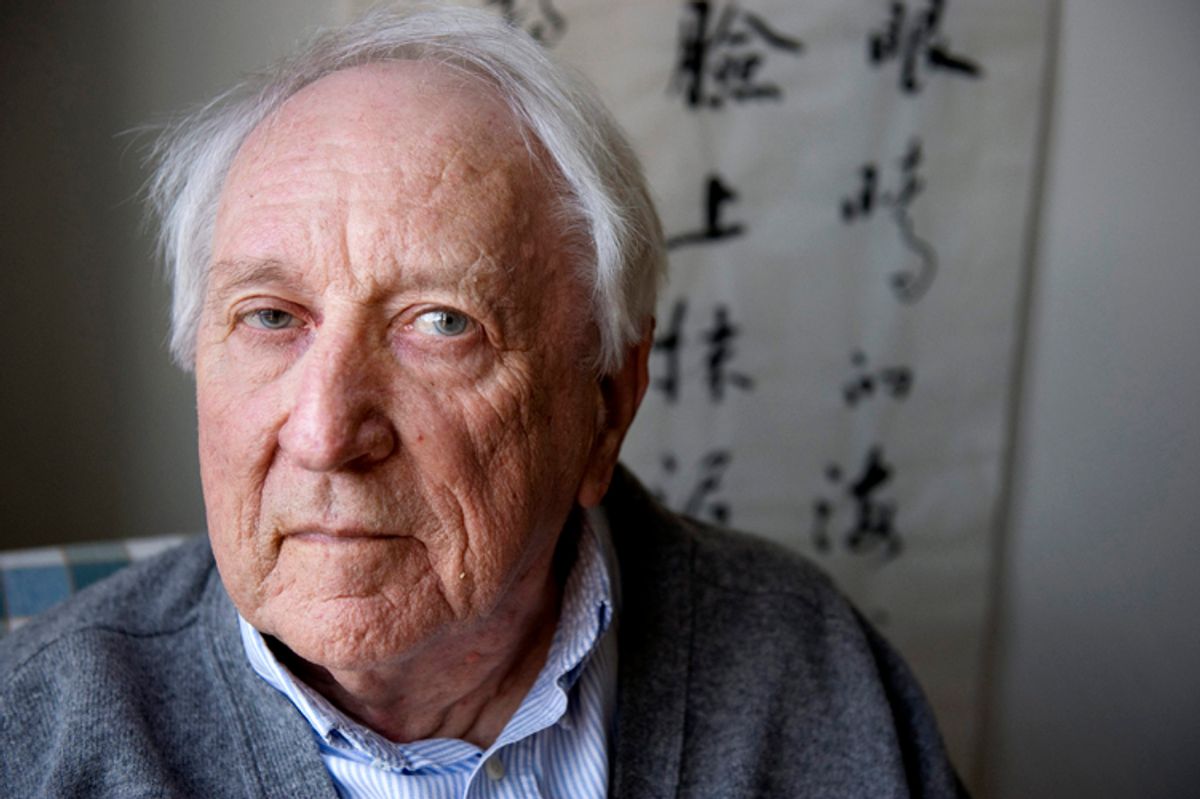

The 2011 winner, Tomas Tranströmer, might be best known to Americans from his appearance on lists of likely winners this time every October. Five years ago, the Guardian called him "Scandinavia's greatest living poet." Now he is the 108th Nobel laureate in literature, in the company of Yeats, Hemingway, Beckett, Faulkner and García Márquez (not to mention the satisfyingly crotchety Doris Lessing).

Tranströmer is the first Swede to win the prize since the early ‘70s, and the first poet to be recognized by the prize committee in 15 years. (Despite the Academy’s avowed intent to achieve a greater "global distribution" in its laureates, his win is also part of a firmly European trend; only two of the last 10 laureates hail from non-European countries.)

So what is his work like?

"Through his condensed, translucent images," the Academy said of Tranströmer in a statement this morning, "he gives us fresh access to reality." This sentiment echoes a profile of the poet from his British publisher Bloodaxe Books, which notes:

In Sweden he has been called a "buzzard poet" because his haunting, visionary poetry shows the world from a height, in a mystic dimension, but brings every detail of the natural world into sharp focus. His poems are often explorations of the borderland between sleep and waking, between the conscious and unconscious states.

The octogenarian laureate has had twin careers as a poet and psychologist, with his work in the latter field focusing in particular on "juvenile offenders." While he is not, in the words of Swedish Academy Permanent Secretary Peter Englund, "prolific" ("you could fit [all his work] into not too large a pocket book," the Nobel spokesman claims), Tranströmer has had a lengthy writing career; his first volume of poetry was published when he was in his early 20s.

In a brief video interview recorded shortly after the announcement of Transförmer’s win, Englund said, "You can never feel small after reading the poetry of Tomas Tranströmer," recommending that the uninitiated start with two Tranströmer volumes, both of which are available in English translation: "The Half-Finished Heaven" and "The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems." Others recommend starting elsewhere -- for instance, with the 1974 work "Baltics."

A 1990 stroke -- as a result of which he can no longer speak, and is paralyzed on his right side -- left Tranströmer with serious physical handicaps, but failed to stem his creative impulses. (He addressed the life-changing event in his work "The Sorrow Gondola.")

Music plays a powerful role in his written work, and in the years since his stroke, Tranströmer has channeled his creativity not only through his writing, but also through the piano (the instrument is a lifelong "passion," according to the poet's unofficial website), which he plays with just the five fingers of his left hand. You can hear a recording of his music here:

02-Zdenko Fibich Andante ur Stimmungen, Eindrucke und Erinnerungen op. 47 by bro1045

In a pensive 1989 interview, the poet placed himself firmly in the Modernist camp, discussing the elements of his writing that are uniquely informed by his Swedish heritage -- a preoccupation with weather, the influence of Baltic sensibilities, even a keen interest in nature that can perhaps be chalked up to the legacy of Linnaeus. He also praised his friend and frequent translator Robert Bly, lamenting that it was sometimes difficult for Swedish poets to find gifted translators capable of rendering their own verse into artful English:

I’m lucky because I’ve been translated by poets who happen to know some Swedish, but it’s not so common with a small language like Swedish -- it’s more common that you are in the hands of a specialist in the language who might have very little interest or feeling for poetry. ... It’s a sad fact that so many of our best Swedish poets are untranslatable because the structure of their writing comes too close to the structure of the Swedish language and this makes them almost impossible to translate. And other poets can be translated easily. It’s the same in all languages.

As to Tranströmer's politics, Bill Coyle wrote in 2006 that the poet was "unlikely" to win the Nobel precisely because his work is not overtly political:

There’s also the unfortunate fact that the choice of [Nobel] recipient often seems guided as much by politics as by literary considerations. Tranströmer is not an apolitical poet, but there is nothing about him -- no confinement by the state, like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn or Joseph Brodsky, no sense that he speaks for his people, like Heaney or Walcott, no rabid opposition to the United States, as with Pinter -- to excite the more narrowly political.

On the same topic, Tranströmer himself has said (in the same 1989 interview quoted above): "I am very interested in the politics but more in a human way than in an ideological way."

Like many of the other authors whose names have been batted around speculatively over the past few weeks, Tranströmer has been no stranger to Nobel gossip over the years; he’s been in the running (informally, of course -- nominations are not revealed for 50 years after a Nobel Prize has been awarded) for at least two decades. In fact, it is a measure of his sheer staying power that he receives these Nobel laurels a full 21 years after he was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature. (He’s earned several other prizes -- such as a Lifetime Recognition Award from the Griffin Trust for Excellence in Poetry -- since.)

A decade ago, reviewer Noah Isenberg wrote of Tranströmer in the New York Times: "[The poet]’s direct, elegant style is perhaps best encapsulated in a line from his poem 'Preludes': 'Truth doesn't need any furniture.'" While the same is arguably true of literary talent, Tranströmer’s lifetime of eloquence renders this new, distinguished decoration richly deserved.

Hear Tranströmer discuss one of his own works, "Schubertiana," below (via tomastranstromer.net) -- and, for more from the Nobel Prize Committee (or to send Tranströmer a personal "greeting") visit Nobelprize.org.

Shares