The teeming crowds of supporters who had cheered candidate Barack Obama’s agenda for “change you can believe in” receded quickly. The 2008 presidential election energized Americans who had never participated in politics before, particularly the young and minorities, and it attracted the interest and hopes of many independents, people who are usually less engaged in the political process. Once elected, the young president held to his word and pursued transformations in American social policy -- healthcare reform, new tax breaks, and enhanced aid to college students -- that vast majorities of Americans had long told pollsters they favored. Despite the usual travails of the legislative process, exacerbated in 2009 and 2010 by greater political polarization in Congress than at any other point in the post–World War II period, within 15 months Obama had already achieved much of what he set out to do on these issues. Yet Americans generally seemed unimpressed and increasingly disillusioned. The problem was that most of what was accomplished could not be seen: It remained invisible to average citizens.

The public had no trouble noticing the jockeying of special interests that sought favored treatment in legislation -- that was plain to see -- but the majority of Americans remained unaware of the contents of the president’s signature achievements, and they lacked a basic understanding of how they and their families might be affected by them. The first major piece of legislation that Obama had signed into law, the stimulus bill of February 2009, included a vast array of tax cuts: They totaled $288 billion, 37 percent of the cost of the entire bill. Among them, the Making Work Pay Tax Credit, one of his campaign promises, reduced income taxes for 95 percent of all working Americans. Yet one year after the law went into effect, when pollsters queried the public about whether the Obama administration had raised or lowered taxes for most Americans, only 12 percent answered correctly that taxes had decreased; 53 percent mistakenly thought taxes had stayed the same; and 24 percent even believed they had increased!

Healthcare reform represented Obama’s chief policy goal, and he expended a vast amount of political capital in pursuing it over his first 15 months in office. But in April 2010, just weeks after he signed the healthcare bill that extended coverage to the vast majority of working-age Americans and prohibited insurance companies from denying coverage to people who are ill, 55 percent of the public reported that they would describe their feelings about it as “confused.”

That same legislative package also contained sweeping changes in student aid policy that aimed to help more people attend college and complete degrees. Yet when Americans were asked how much they had heard about these changes, only 26 percent reported “a lot,” while 40 percent said “a little,” and fully 34 percent said “nothing at all.”

All told, the public seemed largely oblivious to the president’s major policy accomplishments.

While many who had voted for Obama grew complacent, grassroots mobilization emerged from another quarter, the insurgent Tea Party movement. Wielding placards at protests on tax day, town hall meetings and other public events, its supporters decried what they termed “government takeovers” of healthcare and student loans. At a gathering in Simpsonville, S.C., in August 2009, one man told Republican Rep. Robert Inglis, “Keep your government hands off my Medicare.” Inglis said later, “I had to politely explain that ‘Actually, sir, your healthcare is being provided by the government,’ but he wasn’t having any of it.”

While as of March 2010 only 13 percent of Americans reported that they considered themselves “part of the Tea Party movement,” nonetheless the frustration that it embodied resonated with growing numbers of Americans: 28 percent considered themselves supporters.

With the content of Obama’s legislative accomplishments appearing so opaque and incomprehensible even as the calls of opponents resonated loud and clear, most Americans registered reactions that were tepid at best, and many grew increasingly hostile. By the fall of 2010, 61 percent of likely voters told pollsters they favored a repeal of healthcare reform.

It was a sharp contrast to the warm reception given to sweeping social welfare laws achieved by earlier presidents. After Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law the Social Security Act of 1935, 68 percent of the public voiced support for its “contributory old age insurance plan ... which requires employers and workers to make equal contributions to workers’ pensions” -- even though its benefits were not scheduled to begin for six years.

When Congress passed Lyndon Baines Johnson’s plan for Medicare in 1965, strong majorities repeatedly said they approved of it, as high as 82 percent in a December survey that year.

Until Obama’s presidency, perhaps never before had major laws that aimed to improve the lives of vast numbers of ordinary Americans gone so unrecognized and unappreciated by so many.

What explains the public’s reticence, frustration and confusion? Certainly its reactions owe partly to the worst economic conditions since the Great Depression, with more than two years of near 10 percent unemployment. Some of the lackluster response was inevitable, furthermore, given the sheer scope and complexity of the policy tasks Obama took on. And a share of the blame belongs to his administration’s own public relations efforts, which many observers considered underwhelming. Yet while each of these commonly cited factors undeniably played a role, they do not, by themselves, explain Americans’ blasé response to major social policy accomplishments that reflected broadly shared values. Historical comparisons make this evident. The public voiced its high approval for the Social Security Act of 1935, for example, when the nation was still mired in the Great Depression and when twice the proportion of Americans, 20 percent, remained jobless. That legislation was also multifaceted and complex, and it was even more novel for the United States than the 2010 healthcare package, marking the first major involvement of the U.S. federal government in social provision for people besides veterans and their relatives.

The main difference confronted by Obama emanated from the types of policies that he sought to reform, ones that generate particularly formidable obstacles. Any leader who seeks to transform “politics as usual” is bound to confront resistance -- challenges emanating from the policies, practices and institutions already in place.

But the nature and difficulty of the task vary depending on the particular goals that reformers select and the historical context in which they pursue them. Roosevelt confronted a political landscape that presented its own challenges -- not least, a Supreme Court that served as a major roadblock to his policy ambitions. His administration had to attempt to fashion policies that would circumvent the court’s reach and to build as much as possible on what already existed, such as social policies adopted by some states. But Obama’s policy agenda, in the current political context, requires him to engage in a struggle more akin to that undertaken by Progressive Era reformers, who had to destroy or reconstitute deeply entrenched relationships if they were to achieve change.

He could not follow the path of Roosevelt, finding a way around political obstacles or merely building on top of what existed; rather, he had to find ways to work through them, by either obliterating them or restructuring them.

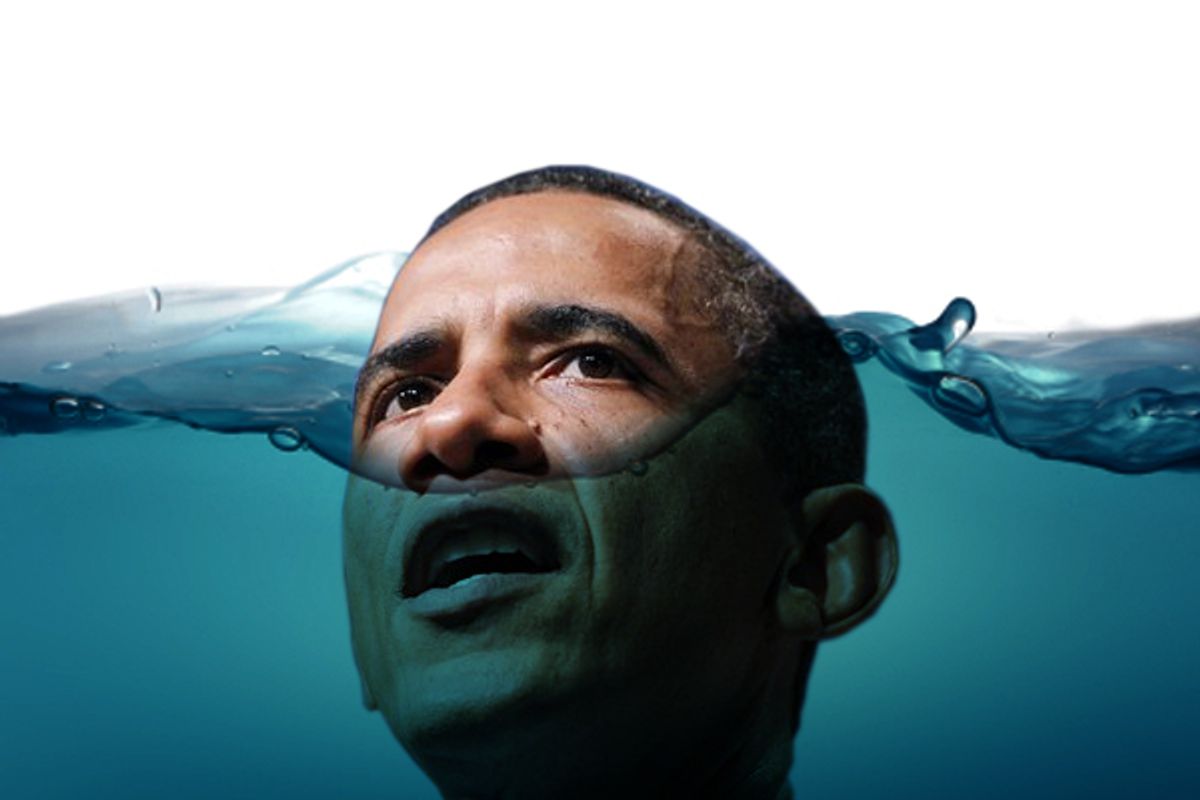

This is because Obama, given his policy agenda, had steered directly into the looming precipice of the submerged state: existing policies that lay beneath the surface of U.S. market institutions and within the federal tax system. Contrary to opponents’ charges that his agenda involved the encroachment of the federal government into private matters, Obama was actually attempting to restructure a dense thicket of long-established public policies, but ones that are largely invisible to most Americans -- and that are extremely resistant to change. Efforts to transform these policies, which have become entrenched fixtures of modern governance, generate a deeply conflictual politics that routinely alienates the public, hindering the chances of success or the sustainability of the reforms.

The “submerged state” includes a conglomeration of federal policies that function by providing incentives, subsidies or payments to private organizations or households to encourage or reimburse them for conducting activities deemed to serve a public purpose. Over the past 30 years, American political discourse has been dominated by a conservative public philosophy, one that espouses the virtues of small government. Its values have been pursued in part through efforts to scale back traditional forms of social provision, meaning visible benefits administered fairly directly by government. In the case of some programs geared to the young or to working-age people, the value of average benefits has withered and coverage has grown more restrictive.

Ironically, however, the more dramatic change over this period has been the flourishing of the policies of the submerged state, which operate through indirect means such as tax breaks to households or payments to private actors who provide services. Since 1980 these policies have proliferated in number, and the average size of their benefits has expanded dramatically.

Most of these ascendant policies function in a way that directly contradicts Americans’ expectations of social welfare policies: They shower their largest benefits on the most affluent Americans. Take the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction (HMID), for example, which is currently the nation’s most expensive social tax break aside from the tax-free status of employer-provided health coverage. Let us assume that a family buys a median-value home and to finance it borrows $230,000 at an interest rate of 6.25 percent for 30 years. The richer the household, the larger the benefit: In the first year, the average family, with an income between $16,751 and $68,000, would owe around $3,619 less in taxes; those in the next income group, with earnings up to $137,300, would reap an extra $5,146; and so forth, on up to the wealthiest 2 percent of families, with incomes over $373,650, who would enjoy a savings of $6,673. Of course, in reality, these differences are likely to be much greater. Low- to moderate-income Americans usually do not have enough deductions to itemize, so they would forgo this benefit and receive instead only the standard deduction. Meanwhile, the most affluent are likely to purchase far more expensive homes; if a family in the top income category opts for a more upscale home and borrows $500,000 for a mortgage, it will reap a benefit of $14,506 from the HMID; if this family purchases a truly exclusive property and borrows $1 million for a mortgage, it will qualify to keep a whopping $29,012!

This pattern of upward redistribution is repeated in numerous other policies of the submerged state: Federal largesse is allocated disproportionately to the nation’s most well-off households. Such policies consume a sizable portion of revenues and leave scarce resources available for programs that genuinely aid low- and middle-income Americans.

Yet despite their growing size, scope and tendency to channel government benefits toward the wealthy, the policies of the submerged state remain largely invisible to ordinary Americans: Indeed, their hallmark is the way they obscure government’s role from the view of the general public, including those who number among their beneficiaries. Even when people stare directly at these policies, many perceive only a freely functioning market system at work. They understand neither what is at stake in reform efforts nor the significance of their success. As a result, the charge leveled by opponents of reforms -- that they amount to “government takeovers” -- though blatantly inaccurate, makes many Americans at least uncomfortable with policy changes, if not openly hostile toward them.

Exacerbating these challenges, at the same time as the submerged state renders the electorate oblivious and passive, it actually promotes vested interests, and it has done so especially over the past two decades. The finance, real estate and insurance industries all thrived until the recent recession, and in turn they invested heavily in strengthening their political capacity, making them better poised to protect the policies that have favored them. As a result, reform has required public officials to engage in outright combat or deal making with powerful organizations. Such politics disgust most Americans and hardly epitomize the kind of change Obama’s supporters expected when he won office.

Other presidents over the past century focused their energies on legislative battles that were far more visible and thus more comprehensible to the public. Towering figures such as Roosevelt and Johnson seized the power of the “bully pulpit” to create the major direct social programs of the New Deal and the Great Society. More recently, presidents have sought to engage in retrenchment, efforts to terminate or to reduce dramatically the size of programs, but here again they concentrated on visible forms of governance. Ronald Reagan took the lead on this approach, telling the nation, “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

While he failed to abolish full programs, some were curtailed in scope, and benefits stagnated in several that were not protected by mandatory automatic increases. Early in his presidency, Bill Clinton did set out to restructure some components of the submerged state but met with little success, failing at healthcare reform and achieving only a modest beginning on student loan reform. Thereafter, he turned instead to the highly visible task of attempting to “end welfare as we know it,” while simultaneously enlarging the submerged state through new and expanded tax breaks. By contrast to all of these, Obama took on an especially daunting agenda: He prioritized an entire set of social policy issues that each required transformation of the submerged state in order to be accomplished.

Against great odds, Obama has largely succeeded in these pursuits, achieving both healthcare reform and major student aid legislation. Yet even these and other new policies he has signed into law still cloak government activity in ways that may make it largely imperceptible to most citizens. Their designs hinder Obama’s ability to accomplish the broader goals he articulated during his campaign, namely, “reclaiming the meaning of citizenship, restoring our common sense of purpose,” and to “restore the vital trust between people and their government.”

The problem is not simply the typical policy complexity that alienates the public; rather, policies of the submerged state obscure the role of the government and exaggerate that of the market, leaving citizens unaware of how power operates, unable to form meaningful opinions, and incapable, therefore, of voicing their views accordingly.

American politics today is ensnared in the paradox of the submerged state. Our government is integrally intertwined with everyday life from healthcare to housing, but in forms that often elude our vision: Governance appears “stateless” because it operates indirectly, through subsidizing private actors. Thus, many Americans express disdain for government social spending, incognizant that they themselves benefit from it. Even if they do realize that the benefits they utilize emanate from government, often they fail to recognize them as “social programs.” People are therefore easily seduced by calls for smaller government -- while taking for granted public programs on which they themselves rely.

Meanwhile, economic inequality has soared in the United States over the past 40 years, reaching levels not seen since 1929. Yet over this same period, policymakers have adamantly protected submerged-state policies that bestow their greatest rewards on the affluent.

Ordinary citizens fail to realize the upward bias of such policies. Political leaders who do seek to reform them, to make their benefits more accessible to Americans of low and moderate incomes, face charges of mounting a “government takeover.” If against the odds they manage to succeed, the policies achieved, especially if they still cloak government’s role, prove difficult to sustain.

Change is possible, however. We can expose the submerged state, reveal governance, and consequently enable citizens to become more engaged and active, reclaiming their voice in the political process. In order to make it possible to carry out reform, first policymakers must reconfigure the role of vested interests. To make reform meaningful, they must alter policies in order to ameliorate their bias toward the affluent. These changes alone, however, will be hard to achieve and even more difficult to sustain, and they will thwart the renewal of citizenship, unless leaders can transform policies to reveal to ordinary Americans their existence and basic effects. To facilitate this, specific strategies must be adopted at the stages of both policy enactment and subsequent implementation. Through policy design and delivery, as well as political communication, policymakers can shift the balance between visible and hidden policies, foster a basic awareness of government, and broaden participation in politics.

As long as the submerged state persists in its shrouded form, American democracy is imperiled. Contrary to popular claims, the threat to self-governance is not the size of government, but rather the hidden form so much of its growth has assumed, and the ways in which it channels public resources predominantly to wealthy Americans and privileged industries. We can reclaim governance, however, making it more visible and comprehensible to ordinary Americans, and using policies to ameliorate rather than to exacerbate inequality. With political will and purposeful action, public policy can be refashioned to revitalize democracy.

Reprinted with permission from The Submerged State: How Invisible Government Policies Undermine American Democracy, by Suzanne Mettler, published by the University of Chicago Press. @2011 The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Suzanne Mettler is the Clinton Rossiter Professor of American Institutions at Cornell University. Her most recent book is "Soldiers to Citizens: The G.I. Bill and the Making of the Greatest Generation."

Shares