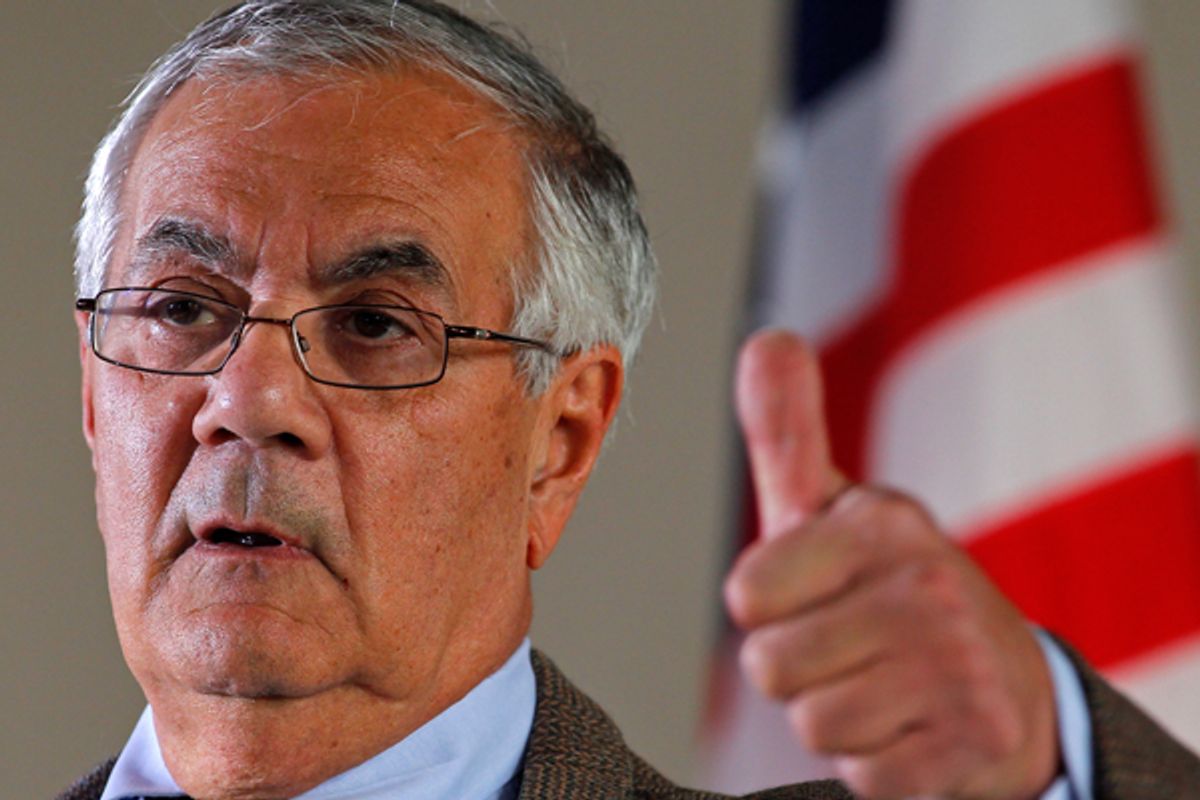

I was sorry to see Barney Frank retire. He’s a good guy. He meant well. That’s what my mother used to say about a well-intentioned but ineffectual person, like maybe the butcher who threw in an extra piece of meat that wasn’t chewable.“He means well,” she’d say.

Or, like the nice kid who used to get beaten up by bullies, Frank was always unafraid to go on Fox News and mix it up with Bill O’Reilly. The right hated him, pushing the trope that “Fannie and Freddie” were the cause of the 2008 financial crisis, not the banks. Or the Community Reinvestment Act, not the banks. Always the government, never the banks. The criticisms stung, even though baloney like the CRA yarn had been refuted “up, down and sideways,” as Paul Krugman once pointed out.

Barney Frank was the nice kid on the block who worked hard, producing the major legislation bearing his name that is now being sentimentally lauded upon his imminent passing from the scene. The Dodd-Frank law, which dominates today’s eulogies, surely meant well. If it didn’t, it would not be targeted by the Republican presidential candidates, notably the phony populist Ron Paul.

The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was the only legislative reaction to the 2008 financial crisis. It’s understandable in a time of legislative gridlock that we would look back with nostalgia on any positive accomplishment by Congress, anything that would not turn back the clock, no matter how weak. And make no mistake about it: Dodd-Frank was, and is, weak.

It had many good features, to be sure. As I said, it meant well. But as market reform it was a flop, for the simple reason that it was not intended to be market reform. It was, instead, a political reaction to the crisis that did not go far enough, and did not purport to do so.

Its primary weakness is that it was not a clear response to the actual causes of the financial crisis. As subsequently recounted by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission and every serious study of the crisis, what up-ended the economy was serial recklessness by major banks that simply could not be trusted to self-regulate. But Dodd-Frank did not reverse the tide of self-regulation, or even take back the goodies that Congress had piled on the banks over the years.

Probably the worst of these was the repeal in 1999 of the Glass-Steagall Act, which was enacted during the Depression and which separated commercial from investment banks. Repeal took place during the Clinton administration, and was heavily promoted by Alan Greenspan and Robert Rubin, the Goldman Sachs and, later, Citigroup executive, who was Clinton’s primary interlocutor with Wall Street.

The end of Glass-Steagall was the chief enabler of the financial crisis. It paved a way for monstrosities such as the behemoth that is now JPMorgan Chase. John Cassidy observed in the New Yorker that as the mergers continued between investment and commercial banks, “the remaining Wall Street firms, grappling with new competition in their traditional businesses, increased their borrowing and made riskier bets.”

Having gotten rid of Glass-Steagall before the crisis, it would have been logical to restore it afterward. Robert Reich noted while Dodd-Frank was crawling through Congress that “No public interest has been served by allowing the casino called investment banking to merge with the traditional intermediary function linking savers to borrowers. In fact, it's caused nothing but trouble.” He was right. But Glass-Steagall was never reenacted.

Dodd-Frank also failed to address another root cause of the financial crisis, which was the rollback since Reagan of consumer protection rules and the weakening of banking and securities regulators. The too-big-to-fail banks like Merrill Lynch had loaded up on subprime securities, and the subprime crap came into existence because of mortgage lenders’ ability to hoodwink borrowers into taking on mortgages with terms so murky that the sellers did not always understand them.

The solution was a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which originally was to be a separate agency but was folded into the Federal Reserve, thereby coming under the aegis of Wall Street’s tool, Timothy Geithner. And then, of course, President Obama, who also means well but is loath to go to the mat with Congress, made the CFPB toothless by failing to push for Elizabeth Warren as its first chief.

As Dodd-Frank crept through Congress, it was steadily weakened. The Senate voted down a ban on a pernicious derivative, naked credit default swaps. An attack on “too big to fail” — explicit size limitations for financial institutions — was also kept out of Dodd-Frank, even though the humongous size of financial institutions made necessary the bailouts that Congress supposedly despised. There was no serious limit on executive compensation, even though lust for bonuses was also a direct cause of the recklessness that nearly sabotaged the economy. Instead of Glass-Steagall repeal, the Volcker Rule banning bank proprietary trading was enacted. But by the time it emerged from the rule-making mix-master, the rule was so complex as to be almost useless.

Frank knew perfectly well that Dodd-Frank was watered down because of interference from the GOP, and said so. You have to give him credit that he never viewed the legislation in the glowing terms currently being used to describe it.

Obviously, Frank can’t be faulted for the majority of the shortcomings of Dodd-Frank. No congressman, no matter how skilled a negotiator, could have made Dodd-Frank into the market reform mechanism that it was never destined to be. His departure means that a strong voice for regulation will soon be gone. But let’s not forget that the job of the Barney Franks in Congress today is not so much to accomplish anything, as to prevent the sparse achievements of the Obama years from being eroded.

And that's the dilemma. Sure, it's nice to pass low-key legislation that looks nice to the folks at home even if doesn't accomplish very much. Window dressing may even get President Obama reelected. But it won't provide health care to the uninsured, put people back to work — or prevent the markets from being plunged into another crisis.

Shares