It's hard to sell people on a destination located within the earth's crust. For decades, cities have tried to entice us below street level with malls, restaurants, museums and tourist walks. But thrilling to the underground seems to go against our very nature. Put as many Forever 21's as you want down there -- subterranean spaces often end up dingy, depressing and feeling like a grave.

But even if we'll never prefer a basement apartment to a penthouse, or an underground retail district to a walkable street, we might make the space under the sidewalks livable yet. A combination of technological advances and some recent changes in urban dynamics is sending developers onward and downward -- even in New York, where, as Dan Barasch puts it, "People have been trained to think of underground systems as ugly, dirty, smelly and filled with rats."

Barasch and his partner James Ramsey are the co-designers of a wild new public-park concept cast in the mold of the city's acclaimed High Line -- except that instead of hoisting their park into the sky, they want to sink it into the mud. Envisioning a verdant cave filled with grass and trees, the park would be set in an abandoned railroad tunnel underneath Delancey Street in Manhattan, and lit with actual sunlight collected in dishes on the surface. "There are three components," says Ramsey. "You gather the sunlight, concentrate it, then funnel it through fiber-optic cables and distribute it. What that allows you to do is, in effect, create a remote skylight."

Underground sunlight could be the revelation that beneath-the-street development has been waiting for. Photosynthesis is only part of it, though the fact that it will allow vegetation to thrive is a key benefit. Funneling sunlight through fiber-optic cables was pioneered in Japan in the 1970s, but Ramsey says that to his knowledge, nothing that utilizes this technology has yet been attempted on the scale of a public park.

Less dramatic but just as optimistic is Washington, D.C.'s, proposal to breathe new life into the long-sealed concrete passages that run under Dupont Circle. Dupont Down Under was a short-lived (and depressing) shopping corridor located in a set of decommissioned trolley tunnels in the 1990s. Now a group called Dupont Underground is working to reopen the tunnels with a mix of retail and gallery space. Why should such a scheme work the second time around? "We think circumstances are different now," says Braulio Agnese, managing director of the project.

For one thing, D.C. is a safer, cleaner place today, which may make heading underground less intimidating than it used to be. But what will also help, argues Agnese, is a "renewed interest in reclaiming underused urban spaces." This new desire to reclaim is part of an evolving trend called "landscape infrastructure," an eat-every-part-of-the-animal approach to city planning.

Proponents of landscape infrastructure assert that every inch of a city can be used, and sometimes in multiple ways: aqueducts can be boating canals, power-line towers can be viewing platforms, and the little green spaces adjacent to freeway on-ramps can be pocket parks for a game of Frisbee. It's a school of thought that's gaining traction -- both above the surface and below it.

The way cities choose to develop those underground spaces is changing, too. Simply burying a shopping mall hasn't worked well in the past -- success stories like Montreal's Underground City are the exception; gloomy boondoggles, like the seamy Underground Atlanta, are the rule. And those kind of projects are even less likely to work today, because the success of development -- underground or otherwise -- "depends on what market forces are at work during that time," says Barasch. And today's market forces favor unusual, eye-popping amenities that will attract creative, talented workers who are looking for a unique urban experience, not just a pair of jeans at a subterranean Gap.

Underground development, done the right way, could be a perfect fit for this new mode of thinking. Historically, developers have spent a lot of time trying to make underground spaces feel like they're not underground. But the weirdness of an underground park is exactly why we like it. It's intriguing and strange and a little bit spooky. "The underground can be claustrophobic, but it can also be this cozy, Fantastic Mr. Fox layer of reality," says Barasch. So, rather than turn underground spaces into sterile retail or prefab food courts, ablaze with primary colors and piped-in pop music, developers could instead embrace the natural state of these spaces -- their "undergroundness" -- when designing for them. This doesn't mean making them cheerless, it simply means respecting their subterranean identity, much like the High Line kept in place some of the former railroad's industrial decay.

Apple's Fifth Avenue store is a great example of a space that celebrates its undergroundness. As you approach the store, an enormous glass box on the street surface creates an irresistible urge to find out what's beneath it. (This effect works particularly well at night, when it's lit from below.) A grand staircase then spirals downward into a space that, during the day, is well lit by sunlight filtering through the glass box, and at night, provides a tantalizing, almost eerie view of the Manhattan skyline from below. Famed urbanist Witold Rybczynski wrote in 2006 that one problem with underground architecture is that it's hard to make it disappear from view: "Its presence will be felt in a dozen small ways." But Apple has turned that dilemma on its head -- a store that certainly could have afforded a spot on the surface chose to delve underground, and announces that fact with a sparkling obelisk that practically shouts, "We're down here!"

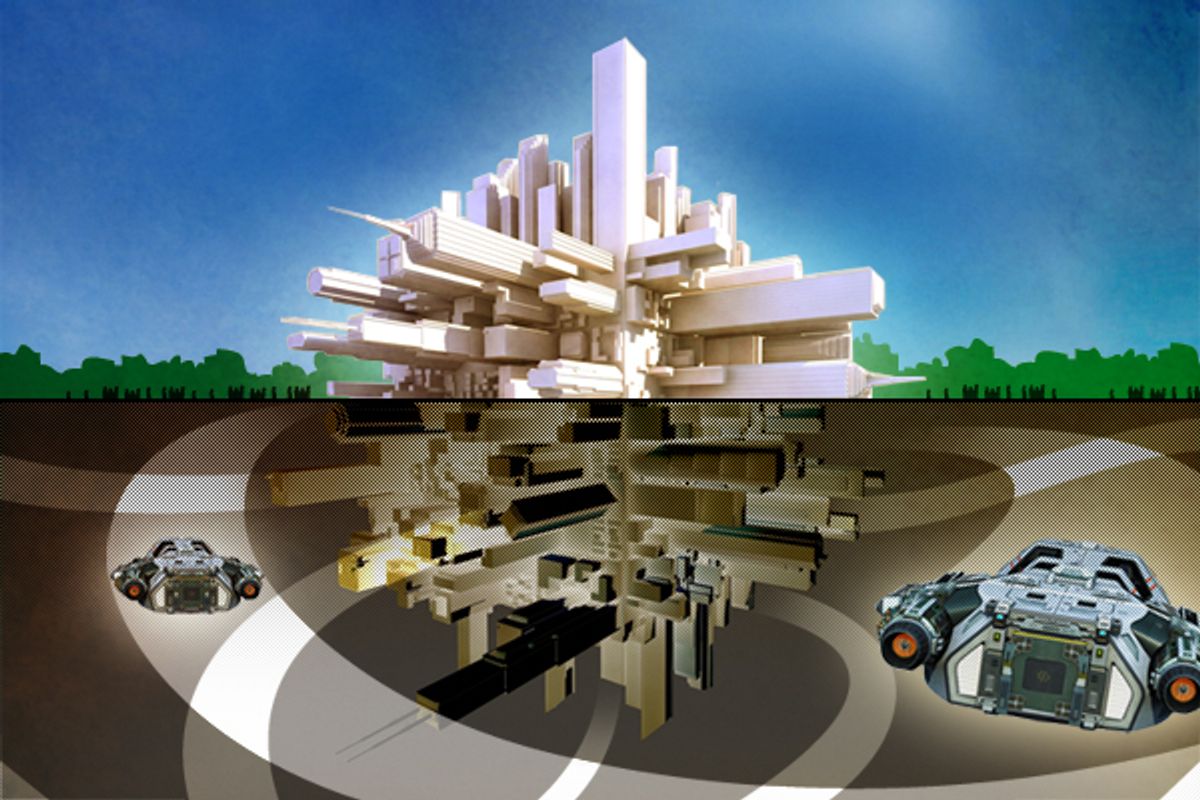

Of course, if we're talking about the next frontier, in which people actually live underground -- and yes, such concepts are being pondered by architects -- we need to make sure it doesn't turn out like "12 Monkeys." To be sure, upside-down high-rises, or "earthscrapers," aren't right around the corner. Myriad conundrums, from ventilation issues to earthquake concerns, need to be addressed. But early schematics are already envisioning some fascinating solutions to these problems. A prototype for an earthscraper in Mexico City, where height-limit laws have created devastating sprawl, includes a series of "earth lobbies" where trees freshen the air, and power-generating turbines are spun by groundwater.

Maybe the biggest issue, though, is justifying the costs. Wouldn't it be easier to just keep building upward? Usually, yes, which is why underground development probably makes most sense when there's already a cavity to be filled. Matthew Fromboluti, a designer with OX Studio, recently proposed an underground building in a 300-acre-wide pit mine in the desert outside Bisbee, Ariz. In situations like this, subterranean construction could actually make more sense than a skyscraper, especially as energy costs rise in the future. "The biggest benefit is that the ground always stays pretty much the same temperature -- around 55 degrees or so. So for hot places, this could be a really great thing."

A hundred years ago, American cities built upward, not only as a space-saving measure, but to showcase their buildings in a feat that dazzled the eye. The next century's underground architecture could astound in a whole new way, as monuments to the notion that every part of a city has value, even those we left for dead and buried long ago.

Shares