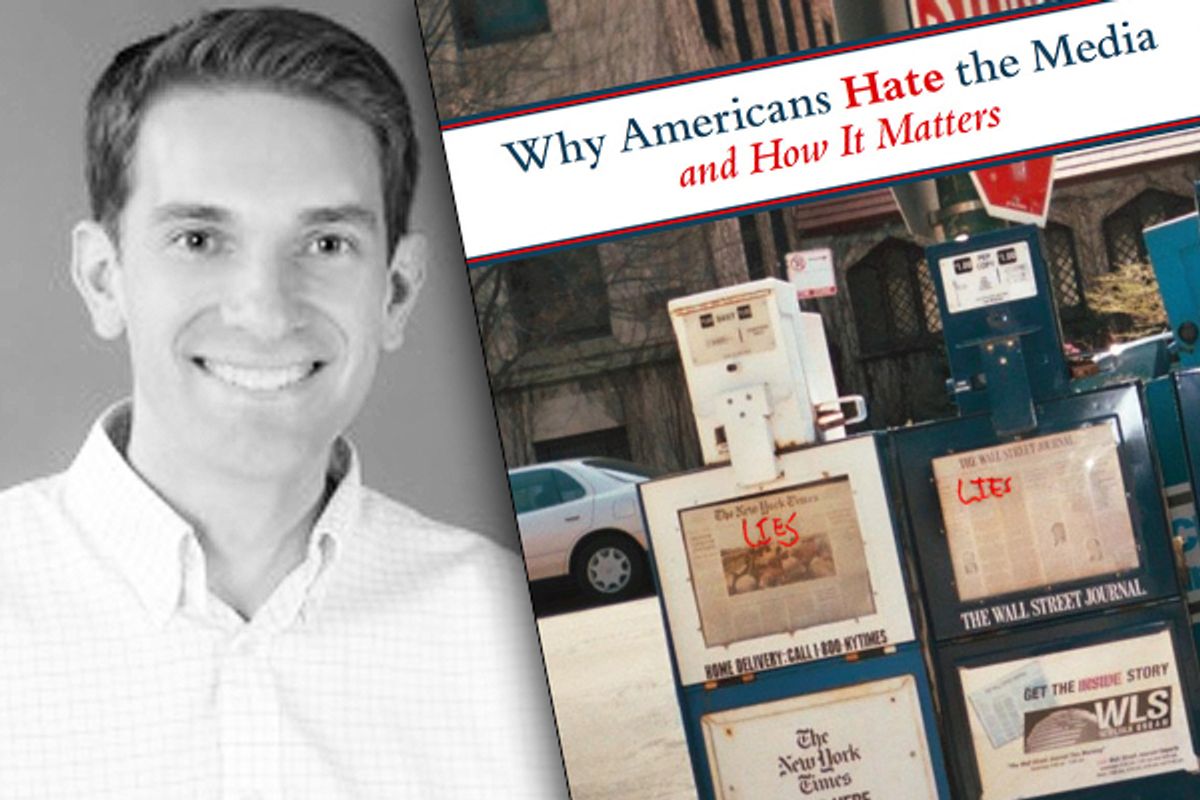

The cover of Jonathan M. Ladd’s new book shows a pair of newspaper vending boxes that have been vandalized. “Lies,” reads the graffiti scrawled across the machines.

Lots of people seem to agree with the sentiment expressed by this anonymous street-level press critic -- even if most of us are more apt to express this by screaming at the TV. In his meticulous and informative “Why Americans Hate the Media and How It Matters,” Ladd cites a 1956 study that “found that 66 percent of Americans thought newspapers were fair.” Within 50 years, things would change dramatically. By 2004, he writes, “only 10 percent of Americans had ‘a great deal’ of confidence in the ‘national news media,’” according to one poll.

Speaking from Washington, where he teaches at Georgetown, Ladd discussed some of the factors that caused such a remarkable about-face -- and how it affects public policy.

Early in the book you point out that “an independent, powerful, widely respected news-media establishment” only began to take root in the middle of the 1900s. Why did this happen when it did?

There were a lot of things about the mid-20thcentury that were unusual. The party system got less polarized, so you had activists with less incentive to attack each other in partisan papers. And there was less competition in journalism. The number of newspapers dropped dramatically in the early 20thcentury. Most small cities in the United States, by the mid-20thcentury, only had one dominant paper. But the (overall) readership stayed about the same, or grew — so more people were reading fewer sources. There was just less competition, so they could produce the style of news they thought was the best. You had the perfect storm for the press to become really trusted.

That’s not how journalism and politics worked in the 1800s, or during the Revolutionary era. It was unusual, so there’s no reason to think that that’s the only way politics and journalism can work well. In a lot of ways, even though the technology is new, we’ve recently adopted a media environment that is more similar to what we had in the past.

You note that FDR in the '30s and '40s, and Richard Nixon in the late '60s and '70s, often publicly criticized the press, but Dwight Eisenhower and JFK — aside from the Kennedy administration’s annoyance about the Bay of Pigs coverage — rarely did this. So here’s a chicken and the egg question: Did Eisenhower and JFK refrain from criticizing the media because the media was respected? Or was the media respected because the presidents didn’t criticize it?

My take is that a lot of the reason that the press was so respected in the '50s and early '60s is that Eisenhower and Kennedy, and the leaders of both parties as well, didn’t feel like they had a big incentive to attack the press so they could get their ideology out. Eisenhower wasn’t really pressing an alternative ideology that the mainstream was stifling. He had a fairly conservative take on what was the consensus ideology of governance at the time, so it wasn’t really in his interest to do that. The parties just weren’t that divided, so no one had a huge incentive to try to discredit the mainstream press. Eisenhower and Kennedy didn’t have much to gain from attacking the mainstream press like Murrow and Cronkite.

Things begin to shift in 1962, with Nixon’s California gubernatorial concession speech, and in '64 with the rise of the Goldwater wing of the GOP, and then with Spiro Agnew and Pat Buchanan monitoring the media coverage of the Nixon White House. As you put it, “There is nothing comparable [on the Democratic side] to the prominent attacks on the media by [the Republican] presidential and vice presidential nominees.” Why has the GOP gone after the media more often than the Democrats over the last 50 years?

As the monolithic institutional news media became trusted and dominant, postwar liberalism and consensus on New Deal social programs was at its height. I suspect that if the media had become monolithic during an era of conservative rule, the press would’ve upheld whatever the elite consensus was then. I don’t think there's anything inherently liberal about an establishment mainstream press. I think they tend to adopt the establishment line, whatever that is, and in the '50s that was a pro-social welfare state line. But because of that historical accident, the people in the Republican Party who saw themselves as true conservatives really saw a mainstream press that was buddy-buddy with the powers-that-be as the enemy. This isn’t ingrained in [liberals’] DNA like it is among conservative activists.

What difference does it make if people hate the media?

People who say they distrust the media in general are more likely to consume news from partisan outlets, outlets that already agree with them, and this will reinforce their positions, whether those positions are right or wrong. I also find a good deal of evidence that when people who distrust the media confront information attributed to the media in general — a lot of the information we encounter we don’t necessarily get as attributed to a single source, but we know has been reported in the media in general — these people don’t absorb that information very well. They’re more likely to reject new information. They form their beliefs about how the country is going, and what’s going on in the world, based on their partisanship.

And this is a great political strategy, to gin up hatred of the media.

Yeah, because you know that people who are going to listen to partisan rhetoric are your supporters to a large degree. So if you criticize the press, you can make it so that your supporters are impervious to new information. For political leaders who want to maximize their amount of votes and ensure that their base is solidly behind them and won’t be moved by any new developments in the real world, this would be a rational strategy — to inoculate your political base against the information by telling them to distrust information that comes from anything except ideological sources.

Is this why, say, the Democrats have such a hard time putting a new healthcare law in place?

I think it might come into play more in people’s assessments of the results of the Affordable Care Act. If you don’t believe any information that’s passed along, you’re more likely to have partisan beliefs about whether healthcare reform has good consequences or bad consequences. People who distrust the media are probably going to be the last people to come to assess the Affordable Care Act based on its actual results.

Here’s a quote from the end of the book: “we should idealize neither the highly institutionalized news media of mid-twentieth century America nor the extreme of a very fragmented, unprofessional news environment toward which the United States has moved recently.” The book suggests that the most fair and healthy media environment would be a hybrid of these two forms. How would this happen?

I want to be cautious about these suggestions because there are downsides to all of these. This isn’t one of these books where I say I have all the answers. But in a more fragmented media world, the government could establish institutions that are more insulated from politics, that try to more accurately publicize the economic performance and how wars are going overseas. The CBO and the Bureau of Economic Analysis at the Commerce Department, which gathers and releases our data on economic growth. The government is quite good at professionally gathering statistics on how the country is doing in a way that’s not politicized. It’s not impossible to say the government could try to use the highly professional bureaucrats to try to publicize information more.

And as with other countries that have a diverse press, one way you can ensure that one type of media is reporting things not in a partisan or a sensational way is to subsidize more of your public media. You could try to cultivate more the public radio and public television model, so that we ensure that some form of news that adheres to the ideal of objectivity still exists.

Hmm. The government is probably trusted less than the press. And there’s a major political party that claims to believe any government is bad government. This would probably meet with lots of resistance.

I think that’s true.

Shares