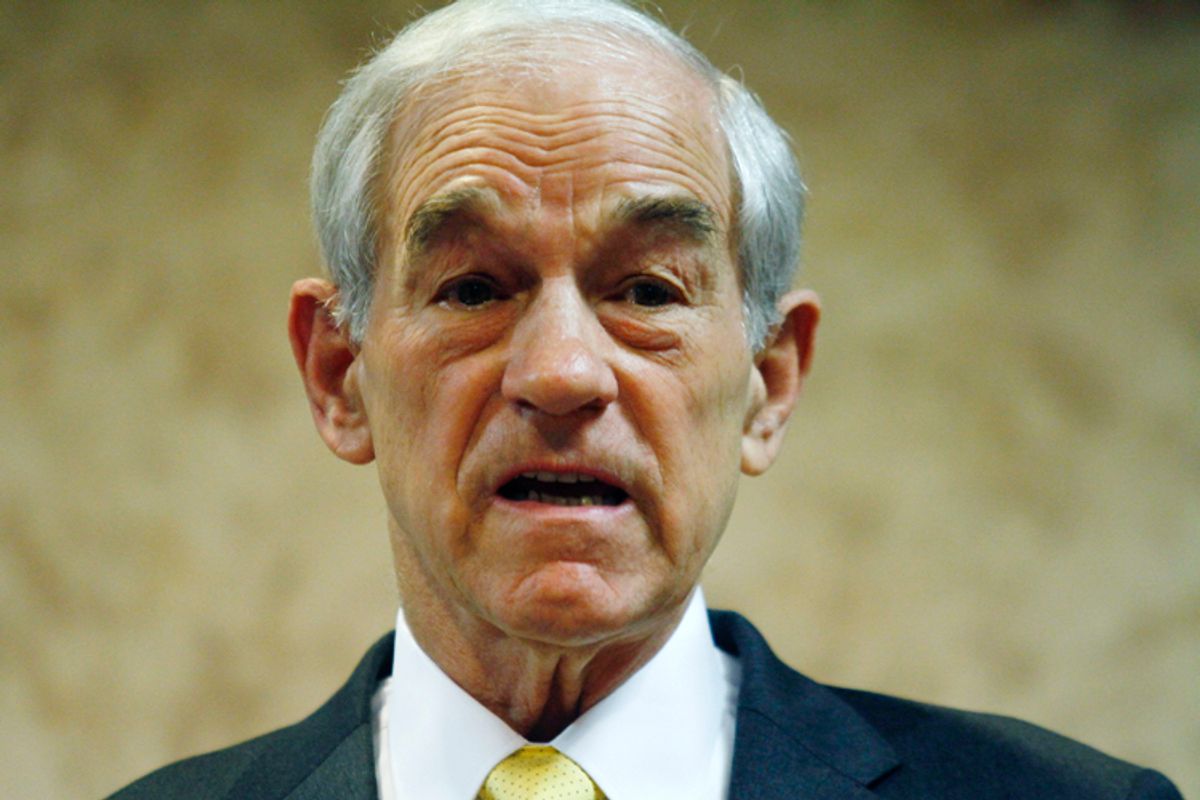

Did the Civil Rights Act of 1964 put America on the path to a police state? The answer is yes, according to Ron Paul, the Texas Republican Congressman and candidate for the Republican presidential nomination. Appearing on CNN’s “State of the Union” on Sunday, Paul explained that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 “destroyed the principle of private property and private choices” and “undermine[d] the concept of liberty.” The candidate drew a direct line from the Civil Rights Act to illiberal legislation passed in the panic that followed the 9/11 attacks: “Look at what's happened with the PATRIOT Act. They can come into our houses, our bedrooms our businesses ... And it was started back then."

By equating the Civil Rights Act, which expanded American civil liberty, with the Patriot Act, which reduced it, on the grounds that both are federal laws with sanctions, Ron Paul displays the moral idiocy of someone who declares that a person who pushes a little old lady out of the path of a bus is just as bad as a person who pushes a little old lady into the path of a bus, because both are equally guilty of pushing little old ladies around.

Like other libertarians, Ron Paul does not understand American values. The American experiment is an experiment in creating and maintaining a democratic republic, not a minimal state. American political culture is founded not on the theories of Ayn Rand or Ludwig von Mises but on the reasoning of natural rights theorists like John Locke, for whom coercion in the service of communal self-defense is perfectly legitimate. In Lockean social contract theory, in order to protect themselves from human predators, people form a community and then transfer the pooled power of self-defense to the community’s trustee, the state, the better to resist invasion and crime. While abuses of military and police power are to be guarded against, the idea that the military and police and government as such are inherently tyrannical, a familiar theme in libertarian and anarchist thought, is utterly alien to America’s Lockean republican tradition.

Libertarians typically argue that only government, backed by military and police power, can be tyrannical. Lockean republicans in contrast believe that private power located in the for-profit or non-profit sectors can be tyrannical, as well. By means of their agent, the state, the sovereign people legitimately can protect themselves from predation by private sector tyrants as well as public sector tyrants.

Libertarians are not the brightest lights in the candelabra, a fact that is evident from the alternatives they tend to offer to public prevention of private abuses. For example: if you don’t like working a hundred hours a week for twenty-five cents a day, then find another employer! It is obvious to intelligent people, if not libertarians, that more generous employers will price themselves out of a market whose standards are set by the most rapacious.

The other popular libertarian remedy for exploitation is to move somewhere else where you will be treated better. But what if you can’t emigrate? Well, it seems, you must suffer your exploitation in silence, rather than enlist the aid of the law in restraining your thuggish employer, your predatory landlord, your exploitative banker or the vendors who sell you toxic food and dangerous products.

Some libertarians concede the legitimacy of government coercion in protecting property rights. But in doing so, these libertarians, like Ron Paul, give up any principled objection to government coercion. They simply want government coercion to be used for some purposes—protecting property rights—and not others—enforcing civil rights.

The Civil Rights Act did not mark an intrusion of government into a realm previously governed purely by what Paul calls “private choices.” Until the federal Civil Rights Act was passed, the coercive power of state and local governments was routinely used to enforce the “private choices” and “property rights” of racists. If a diner owner banned blacks from his diner, and blacks sat down at the counter and insisted on being served, then the diner owner could call the police, who, protecting the property rights of the owner, would drag the would-be black patrons of the restaurant off to jail.

The straightforward way to interpret Paul’s remarks on CNN is to read him as saying that bigoted property owners, like owners of restaurants, should to this day have the right to call on the coercive power of the police department to enforce their decisions to refuse to serve certain categories of customers on their property. Anti-semitic store owners, for example, should have the right not merely to put up a “No Jews” sign, but also to summon the police, at the taxpayer’s expense, to arrest any Jew who insisted on entering the store.

Perhaps I am misreading Paul. Perhaps he does not think that business owners should have retained the right, abolished by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, to have the government, in the form of the police, use coercion to enforce their racist “private choices” to exclude certain classes of clients. Perhaps he thinks that the police should not be involved in the effort to expel the Jew from the Judenrein store. Perhaps true libertarianism means that the anti-semitic store owner should try to persuade the unwanted Jew in the store to leave by noncoercive means—“Shoo, Jew!” Or perhaps authentic libertarianism would sanction private not public coercion, so the Jew-hating store owner should be allowed to hire Slow-Eye Pete and Philadelphia Jack to enforce the store’s No-Jew policy.

But I don’t think this is what Paul meant to say. From his statement that the Civil Rights act “destroyed the principle of private property and private choices,” I think his meaning is quite clear: civil rights legislation at any level—federal, state or local—should never have been passed. To this day, store owners should be free to call on the public police at public expense to drag blacks, Jews, or members of other groups that the owners do not like from their business establishments, in the name of property rights.

Should we be impressed if Paul says that as a personal matter he would oppose such things, while defending their legality? It is hard to see any daylight between an overt racist and someone who claims to oppose racism or anti-semitism, but also denounces the only effective ways to put a stop to them—that is, civil rights laws. If you argue that private racism is bad but anti-racist laws are worse, and if you have no problem with the state’s coercive power when it enforces racism but object to coercive state power only in the service of anti-racism, then you cannot complain when others draw their own conclusions about your motives (even if, unlike Ron Paul, you did not publish white supremacist newsletters for years under your own name).

Abraham Lincoln dissected the sophistical rhetoric of people like Ron Paul, long before the noble word “liberty” was tortured into “libertarianism.” In 1864, during the Civil War, he told an audience:

The world has never had a good definition of the word liberty, and the American people, just now, are much in want of one. We all declare for liberty; but in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing. With some the word liberty may mean for each man to do as he pleases with himself, and the product of his labor; while with others the same word may mean for some men to do as they please with other men, and the product of other men’s labor. Here are two, not only different, but incompatible things, called by the same name———liberty. And it follows that each of the things is, by the respective parties, called by two different and incompatible names———liberty and tyranny.

The shepherd drives the wolf from the sheep’s throat, for which the sheep thanks the shepherd as a liberator, while the wolf denounces him for the same act as the destroyer of liberty, especially as the sheep was a black one. Plainly the sheep and the wolf are not agreed upon a definition of the word liberty…

Shares