Stephen Hawking is the world's most famous living scientist for two reasons that (despite his own wishes in the matter) are impossible to disentangle. The first is his disability, a motor neuron disease related to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, often referred to as Lou Gehrig's disease) that, beginning in his late teens, has rendered him severely disabled. Most people, when diagnosed with ALS, live only a few more years; Hawking has survived for 49, turning 70 on Jan. 8. The second source of renown is his work as a theoretical physicist and cosmologist, particularly on the nature of black holes and the origin of the universe.

Even people with no inclination to tackle the brain-bending concepts Hawking outlines in his bestselling 1988 book, "A Brief History of Time," find his personal story inspiring. In that light, scientific preoccupations they might dismiss as arcane and impractical in an able-bodied person become a metaphor for the human ability to transcend limits. As Hawking himself says in the three-part documentary series "Into the Universe With Stephen Hawking" (you can stream it on Netflix), "Although I cannot move, and have to speak through a computer, in my mind I am free."

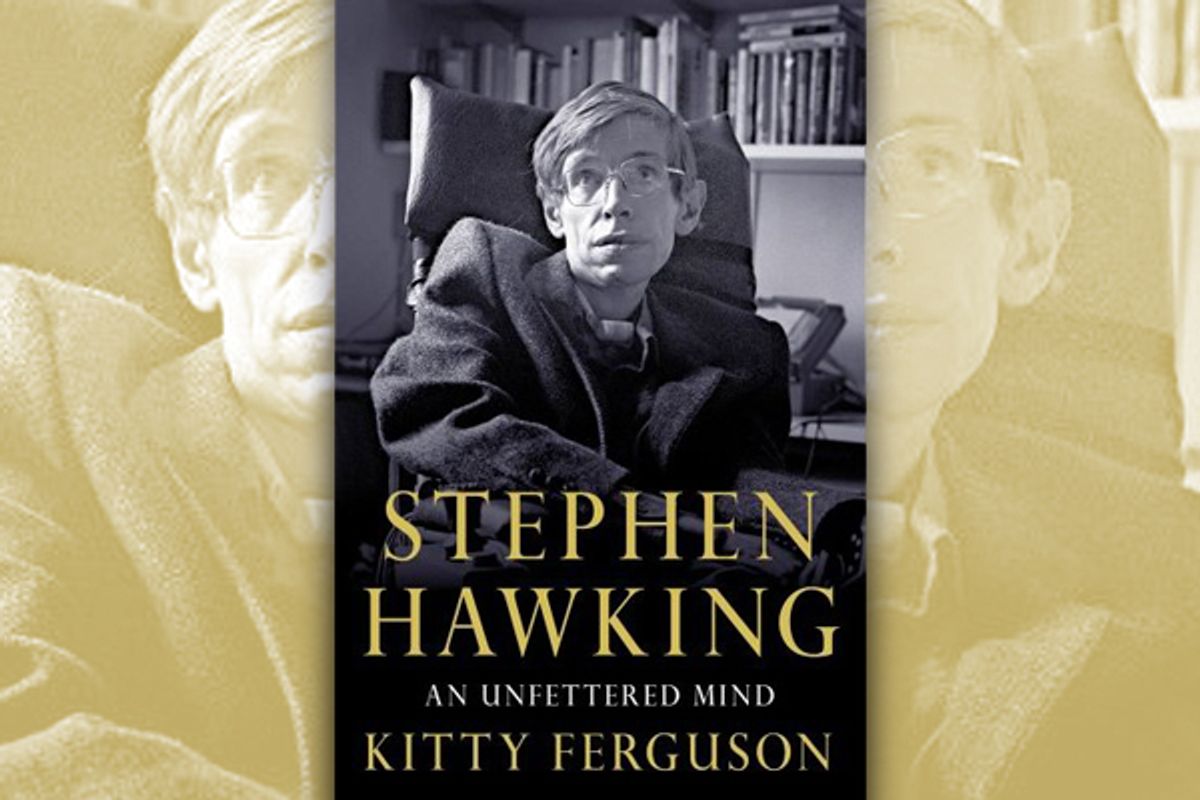

Kitty Ferguson's "Stephen Hawking: An Unfettered Mind," as you might be able to guess from its title, fully subscribes to this view, and who can blame her? It is largely the truth about Hawking's remarkable life. This is the second biography of Hawking that Ferguson has written -- the first was published in 1991. A former neighbor of the scientist and his family in Cambridge, England, she also assisted him with his 2001 book, "The Universe in a Nutshell." "Stephen Hawking: An Unfettered Mind" has both the advantages and the disadvantages of a biography written from such close quarters.

A popular science writer, Ferguson shines at explaining Hawking's theories, the jovially competitive academic world in which they are hammered out and her subject's distinctive and evolving intellectual style. One signal Hawking trait is his "robustly healthy history of pulling the rug out from under his own assertions." This is perhaps most boldly illustrated by the biography's framing device, Hawking's inaugural lecture as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge in 1980. At 38, he foresaw the impending obsolescence of his own field with the discovery of a "theory of everything" that would explain "the universe and everything that happens in it." By the end of the book, he has decided that such an understanding may finally be unattainable, replaced by a "family of theories," known as M-theory, that form a patchwork description of the universe we inhabit.

Another characteristic of Hawking's thought is a move away from "rigorous mathematical proof" toward hunches, or what his longtime friend, physicist Kip Thorne, describes as "high probability and rapid movement towards the ultimate goal." To catch up on Hawking's more recent work is to enter a trippy dream landscape, filled with multiple tiny curled-up dimensions and "baby universes" that are "constantly coming into existence all around us, branching off everywhere, even from points inside our bodies, completely undetected by our senses."

When Hawking was writing "A Brief History of Time," his colleagues cautioned him that every equation he included would cut the book's sales in half. There are no equations here, but there are several diagrams, and at one point Ferguson takes the unusual step of informing her readers that her illustrated explication of one of Hawking's important theories (which is that the universe is finite but has no boundaries, something like the interior surface of a balloon) can be skipped by anyone who finds it too difficult. She also adds that Hawking has approved its accuracy as a simpler description than the one he offered in "A Brief History of Time." That endorsement shows the advantage of working so closely with one's subject.

Ferguson is at her best, however, when sorting through the philosophical implications of Hawking's ideas, especially those in his most recent book, "The Grand Design," which tackles such classic conundrums as why there is something instead of nothing, why the universe operates according to this particular set of laws instead of another, and why we exist. God comes into these discussions a lot, but since Hawking himself is forever invoking the subject, it is not without justification. Hawking seems to take an impersonal, Spinozan view of the matter, in which the laws of the universe are equated with God (a feeling Einstein shared), but his public pronouncements dance back and forth over the line between theism and atheism.

This could be because Hawking knows how just to tweak the public's interest in him as an oracular figure, or it could be a genuine affinity, reflected by the fact that he twice married believers. The intersection of Hawking's personal and scientific life is clearly difficult for Ferguson to get into: for the most part, he adamantly refuses to discuss intimate matters. Hawking's first wife, Jane, wrote an acrimony-free memoir about their 26 years together, and she also seems to be a friend of Ferguson's. His second marriage, which lasted 11 years and ended under a murky cloud of abuse accusations (denied by Hawking himself), remains essentially mysterious. Ferguson seems to think the less said about it the better.

Of course, Hawking's personal struggles can't be separated from his fame. "It wasn't unreasonable to suggest that Hawking's scientific achievement alone would not have made him a celebrity or sold all those books," Ferguson admits at one point. Hawking himself has suggested that his disability, in denying him physical movement, has intensified his ability to hold and solve problems entirely in his mind. But because he (understandably) does not wish to be defined by it, and because he surely owes much of his success to refusing to dwell on what he can't do, the fascinating and perhaps fruitful intersection of his disability and his genius goes largely unexplored here.

Even without a more searching treatment of his character, however, Hawking's remains an irresistible story. His puckish humor and exuberance for life and for ideas are infectious even at a remove. And the ideas themselves could not ask for a better elucidator, not even, dare I say it, Hawking himself. As much as he has relished his celebrity -- the cameo appearances on "Star Trek" and "The Simpsons," the opportunity to travel the world with entourage in tow, the millions of copies of "A Brief History of Time" sold -- it is his work as a theoretical physicist that matters most to the man. Giving the rest of us a glimmer of the wonders swirling inside his head is no small feat, and may be the truest portrait of all.

Shares