PORT-AU-PRINCE — To see where the enormous sums of humanitarian aid directed to Haiti after its catastrophic earthquake in 2010 went, a good place to start is the ocean harbor. That’s where the island’s shore meets the rest of the world. And the best place for that is here at the seaport in the nation’s capital: Port-au-Prince, near the earthquake’s epicenter.

There, at this moment, a gigantic “supermaritime” cargo ship called the Sarine is off-loading more than five metric tons of rice that has just arrived from Miami.

There, at this moment, a gigantic “supermaritime” cargo ship called the Sarine is off-loading more than five metric tons of rice that has just arrived from Miami.

If you think of the rice as post-earthquake assistance money — the individual grains as donated dollars — you might get some idea about what’s happened since the earthquake of Jan. 12, 2010. Not to mention a sense of where the individual rice grains (or the dollars) have gone.

And, like the grains of rice aboard, the dollars mount into the hundreds of millions; even billions. According to some reports, the United States government, American individuals, families and humanitarian groups donated approximately $3 billion. That’s just from America with a total of something like $12 billion coming from all donor nations for funds to be disbursed.

Still, somehow, no one seems quite sure precisely how many grains — or dollars — we’re talking about. The accounting seems to have a sliding scale that can move hundreds of millions of dollars one way or another. At the time of publication, President Bill Clinton, the UN Special Envoy to Haiti and the co-chair of overseeing the nation’s re-construction for the last two years, hasn’t responded to repeated requests by GlobalPost regarding specific aid and cash donation figures.

Where those billions went following the 7.0-magnitude earthquake that left a government-estimated figure of 220,000 people dead — and at least 1.6 million more homeless — remains a confounding mystery. Inside of the recovery effort, however, are unquestionable successes along with the failures. And, to be fair, because the money came in so quickly and in such great volume, much of it has been wasted or lost like so much rice spilling on the docks. Or stolen, like the sacks of rice from here which will end up in Haiti’s black market for food.

The situation grows complicated … fast. And the metaphor here of this crane off-loading rice by the metric ton packs a still larger and more complex metaphor, according to aid experts, about this country’s history along a still-active fault line of aid, politics and blame in the aftermath of the quake.

As for this specific ship, the Sarine, it has a double-steel hull and is roughly 330 feet long. And now, pulled up to the quay in Port-au-Prince, the “grabbing box” from a huge off-load crane reaches down into the vessel’s hold, and, like the hand of God, lifts another half-ton or so of rice out — hundreds of thousands of individual grains of rice. Then the loose rice is dumped into a white, V-shaped steel hopper whose nozzle sits inside a small hut on the Port-au-Prince waterfront.

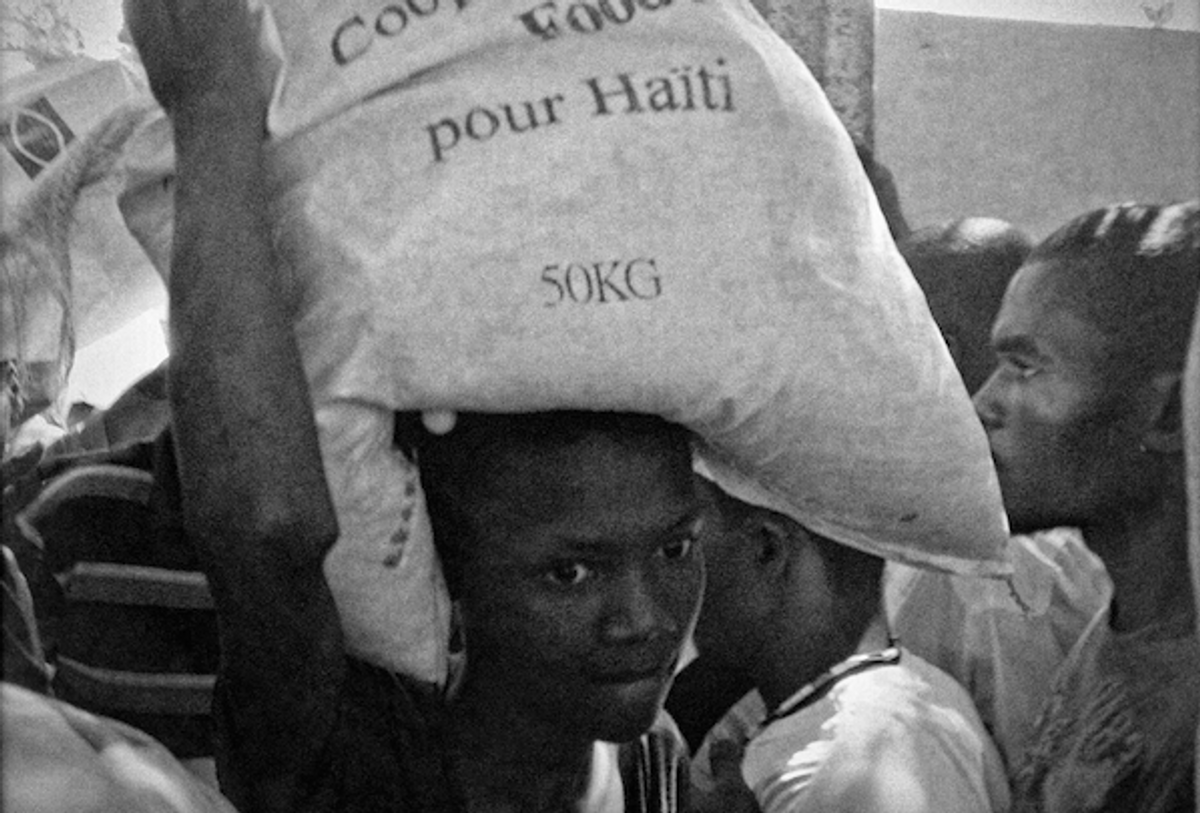

Using gravity, the hopper directs the rice into 25-kg (55-pound) white plastic bags, with blue stars on their fronts and the words “AMERICAN RICE” written on their sides. After that — using a sewing machine — the top of each bag is sealed.

As I watch, over and over — bag after bag after bag — a man running the V-shaped hopper turns to me. He rubs his belly.

“I’m hungry,” he says in French.

“Well,” I respond, “why don’t you take some rice for yourself? There’s a lot.”

The man flashes a grin back, and shrugs. “Yes,” he says, “that’s possible. But I’m not that kind of hungry.”

The rice bags move from the factory along an assembly line to waiting trucks which will travel deeper into Haiti to feed a nation still suffering from hunger on a vast scale.

But the economy of rice in Haiti says everything about the condition the country is in. The U.S. government subsidizes and "donates" ton after ton of rice in Haiti and in so doing has through the last several decades completely undercut Haitian rice farmers and left them destitute and migrating into cities where they live in hovels that were destroyed by the quake.

As recently as the early 1980s, Haiti was producing just about all of its own rice. Now more than 60 percent is imported from the U.S., making it the fourth largest recipient of American rice exports in the world. That was before the quake and now with donated rice coming in as well, Haiti is even more awash in rice while American agribusiness makes billions of dollars every year through generous government subsidies.

There is perhaps some bitter irony here that the subsidies were promoted in large part by President Clinton to help his home state of Arkansas, the largest rice producing state in the U.S., thereby crippling a sector of the economy in Haiti where Clinton has worked so tirelessly to help with the recovery.

“You might say it is a perfect metaphor for what is wrong with aid to Haiti,” says Marc Cohen, a senior researcher for Oxfam, one of the largest non-government organizations (NGOs) in the world, which raised approximately $106 million for a three-year response in Haiti and finds itself struggling to deliver the aid effectively.

“Instead of bringing subsidized rice in on ships from Miami, we could be helping Haiti grow rice in its own fields,” adds Cohen, who worked for many years in Haiti with the International Food Policy Research Institute and studied the broad economic impact of U.S. rice subsidies, or "Miami rice," as it is known here.

Cohen was part of a team at Oxfam America that this week delivered a scathing report on how reconstruction in Haiti was proceeding at a “snail’s pace,” leaving half a million Haitians still homeless two years after the quake. It urged the Haitian government and donor countries to accelerate the delivery of funds for reconstruction. It applauded the initial emergency relief effort, but said the Haitian government and donor countries have failed to come up with a coordinated strategy to rebuild the country and house the more than 500,000 people still living in tents and under tarpaulins without access to running water, a toilet or a doctor.

According to recently published reports by Oxfam, the UN, the U.S. Government Accountability Office and international aid experts interviewed by GlobalPost, billions of dollars of aid were pledged to Haiti’s reconstruction, but promises of funding have not translated into money on the ground. According to the UN report, as of the end of September 2011, donors had disbursed just 43 percent of the total $4.6 billion pledged for reconstruction in 2010 and 2011.

Officials heading up USAID’s efforts in Haiti say they are frustrated by the political and practical realities that slow the pace of reconstruction. They point to costly and painful failures such as the lack of preparedness for the cholera outbreak which still looms over Haiti. But they also point to hard-fought successes particularly in agriculture, where the average salary of a farmer has risen from $600 a year to $1,100 a year through improved irrigation and infrastructure which have resulted in higher yields.

Elizabeth Hogan, Director of Haiti Task Team for USAID, told GlobalPost, “Fixing Haiti is not something that can be done in the short term. It requires Haitians to take ownership of fixing their own country and their own problems with the support of the international community and increasingly private investment.”

A "star-crossed" history

Haiti is a formerly French colonial island nation occupying a little less than half of the Caribbean island originally called Hispanola (the other half of the island, the Dominican Republic, is a former Spanish colony).

Haiti’s capital and gravitational center, Port-au-Prince, is said to be named for the French sailing ship, Prince, which pulled into the island’s harbor in 1706. The island soon became a critical stop in the slave trade in the Americas, with Port-au-Prince being one of the most popular hubs. The colonial overseers grew rich, exporting sugar and coffee to the world.

Because of this history of slavery and repression, some Haitians believe their island is cursed. By 1793, and due somewhat to the slave trade — not to mention a wide-ranging naval war between Britain and France — a British ship called the HMS Hankey, sailing out of West Africa, arrived in Port-au-Prince, carrying with it some West Africans and some British citizens who had been unsuccessful in colonizing a West African island called Bulama. They were also carrying something new.

It was ultimately discovered to be a virus called Yellow Fever, and Haiti was its first New World landfall. The virus killed thousands around Port-au-Prince before the ship sailed for Philadelphia to join a convoy for safe passage back to London. (At Philadelphia, Benjamin Rush, a noted physician of the age, surmised the boat carried some new form of “pestilence” after more then 10,000 Philadelphians died within weeks; he ultimately ordered the ship burned to the water line during its trip home.)

This is the star-crossed history of Haiti. It is a nation blessed by location: it has rich farming soils, a lovely and temperate tropical climate and a stunningly resourceful island populace. It has periods of prosperity and hope that are recent enough for many Port-au-Prince residents — and the millions who live in the diaspora — to remember a time when it was a playground for rich tourists and when it confidently produced most of the food it ate.

But its geographic location makes Haiti uniquely prone to cataclysms such as tropical storms and hurricanes, while what is known in geological terms as the "Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault system," a ragged edge that runs along the North American and Caribbean tectonic plates, has triggered a string of earthquakes over the centuries.

Still, perhaps owing to the island’s difficult past, it remains one of the most hopeful places imaginable. Most of the people living there have historically had very little in the way of resources, and have been ruled and controlled by a small wealthy few, which means any good that comes non-wealthy Haitians’ way tends to be celebrated.

By 1804, due to several slave uprisings, the poor natives overthrew French rule and became the first free nation in Latin America. Like other new democratic successes of the Atlantic World, the Haitians discovered self-determination. They also discovered debt, saddled with a French demand for 150 million francs (more than $20 billion in today’s terms) to compensate the colonial power for its lost territory.

Haiti created home-grown problems, too: despots, self-interested rulers and military coups. Eventually people with names like Duvalier and Aristide and Cedras would become world famous for a power-lust and greed that has defined Haitian leadership. On three occasions in the last century, the U.S. military intervened, including the 20,000 U.S. troops deployed in 2010.

And along with political upheaval came regular hurricanes, mudslides and earthquakes, with international aid often “pledged” but few Haitians ever really seeing it. This exploitation by mercantile forces of seemingly beneficent empires combined with the squandering of aid amid a culture of corruption is the very history of the country, and the contemporary reality in which Haiti finds itself.

In the year following the 2010 earthquake, things were no different. In fact, of the $1.14 billion allocated to Haitian Rebuilding and Relief in 2010 by the U.S. Congress, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (or GAO), only $184 million had been actually “obligated to projects” at the end of 2010. Today as the guys with the green eyeshades get more deeply involved, it becomes clear that in the wake of the Haitian earthquake of 2010 the U.S. government began to pay itself back for its humanitarian graciousness as much as it actually helped the people of Haiti.

Of the original $1.4 billion allocated by Congress, according to a most recent GAO report, $655 million in funds was reimbursed to the Department of Defense (which, admirably, spent its own money to put ships offshore, drop food and medical aid to those who needed it, bring in troops to secure the airport at Port-au-Prince and provide emergency medical services).

Another $220 million went to repay the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (which gave goods, food and grants to Haitian evacuees for food and shelter); $350 million went to disaster assistance (an umbrella term that includes everything from medical care to sanitation); $150 million to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (for emergency food and forward-thinking agricultural programs in Haiti); and $15 million to the Department of Homeland Security for Immigration fees and aircraft fares for the lucky few Haitian refugees brought to the United States.

Expanding the picture doesn’t change it. The UN Special Envoy for Haiti reported that of the overall $2.4 billion pledged by the UN for humanitarian efforts in Haiti, 34 percent (or $864 million) of those funds were given back to donor civil and military organizations, 28 percent (or $672 million) was laid out to UN and non-governmental humanitarian projects such as housing and health-care, 26 percent (or $624 million) was given to contractors for things like road-building and infrastructure, and 5 percent ($120 million) was given to various international Red Cross/Red Crescent societies.

Not that the people of Haiti didn’t benefit from all this money and assistance. But, really, over the last two years, the effort to assist post-earthquake Haiti has mostly benefited — or at least subsidized — the aid and relief institutions and private corporations that nominated themselves to help Haiti in its 2010-based time of need.

“In the end,” says Robert Fatton Jr., professor of government and foreign affairs at the University of Virginia and a son of and authority on contemporary Haiti, “if you read the reports — the UN Report and so on — you’ll see that actual Haitians got less than 1 percent of all the American money pledged.”

In other words, Fatton explained, “99 percent of [the U.S. money spent] went back to the U.S. military, the State Department, NGOs and contractors. The money was clearly intended for Haiti, but it ended up returning to the same place it came from.”

Land Cruiser nation

In a land sometimes referred to as "The Republic of NGOs,” the money that does stay in Haiti often fuels the NGO crowd’s expensive taste for the aesthetic of international aid.

And if you really want to see the face of humanitarian spending post-earthquake in Haiti — the financial clout of the NGOs — there’s only one place to go: the Toyota dealership in Port-au-Prince.

As with any cataclysm or war zone, a white Toyota Land Cruiser is perhaps the ultimate symbol of international interventional power. And in and around Port-au-Prince, the vehicles are omnipresent. At the dealership, a modern and well-tended building on the city’s airport road (with mirrored-glass windows from floor to ceiling and a perfectly buffed showroom floor).

Inside the dealership, we finally run into nice woman in some sort of managerial position, (don’t use my name, she asks). We ask her how sales have been.

“Oh,” she says. “We buy a lot of Land Cruisers for sale to the NGOs. But, you know what? A lot come from Gibraltar, too. Loaded off cargo ships that the NGOs bring for themselves. You can tell those, they say Gibraltar on the back, sort of near the license plate. I’d say — here?— the numbers are probably 50 percent from us and 50 percent from Gibraltar.”

But business is good?

The woman is leaning against a desk in the sales office. “I’d say that, for us, 95 percent go to the NGOs, some go to rental agencies, which then rents them to the NGOs and others. But, you know, for all of the Land Cruisers in Haiti now, we also do the maintenance and repairs, if they get in accidents we fix them.”

How much does one cost?

"Each one, with taxes, is $61,100,” she says. “If you have tax-free status, you can get them for less, but then you have to take them with you or give them away here. If you pay the taxes, you can just sell the car.”

And how many do you sell a year?

The woman holds up her hand, right index finger pointed to the ceiling. “One second,” she says.

She disappears into an outlying office, then returns a minute later. Smiling. “This year, we sold 250 of this model. But, you know, right after the earthquake, for several months, we were probably selling that many Land Cruisers every month. Maybe twice that many.”

I start doing the math in my head. Let’s see: 250 Land Cruisers at $61,000 each is, like, upward of $15 million dollars. So even if they sold only a few more Land Cruisers in 2010 after the first few months (and you have to assume they did) plus the 2011 sales numbers so far (it is December as we’re reporting this), well, conservatively speaking that’s a gross cash influx in the neighborhood of $100 million in the last two years (though of course, some will have to go to taxes). Add to that the repair and maintenance fees, and you’re looking at maybe $110 million. Maybe $150 million. And that’s a conservative estimate.

The woman sees me starting to do the math. She knows this was probably not the right thing to say. After all, if the NGOs figure out that she’s being disloyal, they might not use the dealership anymore. And as the only dealership in the country, maybe all the Land Cruisers would begin to come from Gibraltar. In the world of post-earthquake Haiti, it’s the equivalent of killing a goose laying golden eggs.

She doesn’t want to talk anymore. In so many gentle ways, she suggests our time together is over. As I leave the dealership, I can’t help thinking about all the rice being off-loaded from the Sarine and the money behind it, getting there to help the people of Haiti. Some does appear to get spilled, a little bit, and some of it goes into the bellies (and lives) of the Haitians that need it so badly. But at least, after a week on the ground in this beautiful, star-crossed, and hopeful island nation, now we know a little better where all that money went — or never got to at all.

Shares