For several generations of people too young to remember the civil rights era, Harry Belafonte may seem like a baffling figure, familiar mainly from protest marches seen on television and Caribbean-shtick pop songs heard on grandma's car radio. Who is this elderly African-American celebrity with the Italian-sounding name and the aristocratic demeanor? Why did he become famous in the first place, and why does he sometimes come off as the self-appointed radical conscience of black America? Most famously, Belafonte ignited immense controversy both within and without the black community by repeatedly suggesting that Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice were the "house slaves" of the George W. Bush administration.

Those inflammatory remarks are not mentioned in "Sing Your Song," the rich and fascinating new documentary about Belafonte's life and times, which was written and directed by Susanne Rostock but has clearly been authorized and approved by Belafonte and his family. We learn a great deal about Belafonte's central role as a towering figure of the early-'60s civil-rights movement, when he was confidant and advisor to Martin Luther King Jr. But also unmentioned are his visits to Fidel Castro in Cuba and Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, his warm relations with the Soviet leadership before the fall of communism, or his assertion that George W. Bush was a greater terrorist than those who perpetrated the 9/11 attacks.

For the record, I believe that Belafonte's remarks about Bush are entirely defensible, if impolitic. What he has to say about Barack Obama's first term can only be imagined, because the current president's name, startlingly, is never uttered. (His father's is; Barack Obama Sr. first came to the United States from Kenya by way of a Belafonte-sponsored scholarship.) I don't bring up Belafonte's past associations or overseas visits in order to red-bait him (as his ideological opponents have done exhaustively over the years). My point is that "Sing Your Song" is a vital document of American history, which I recommend to everyone, and also an attempt to massage the patriotic legacy of a complex and polarizing figure.

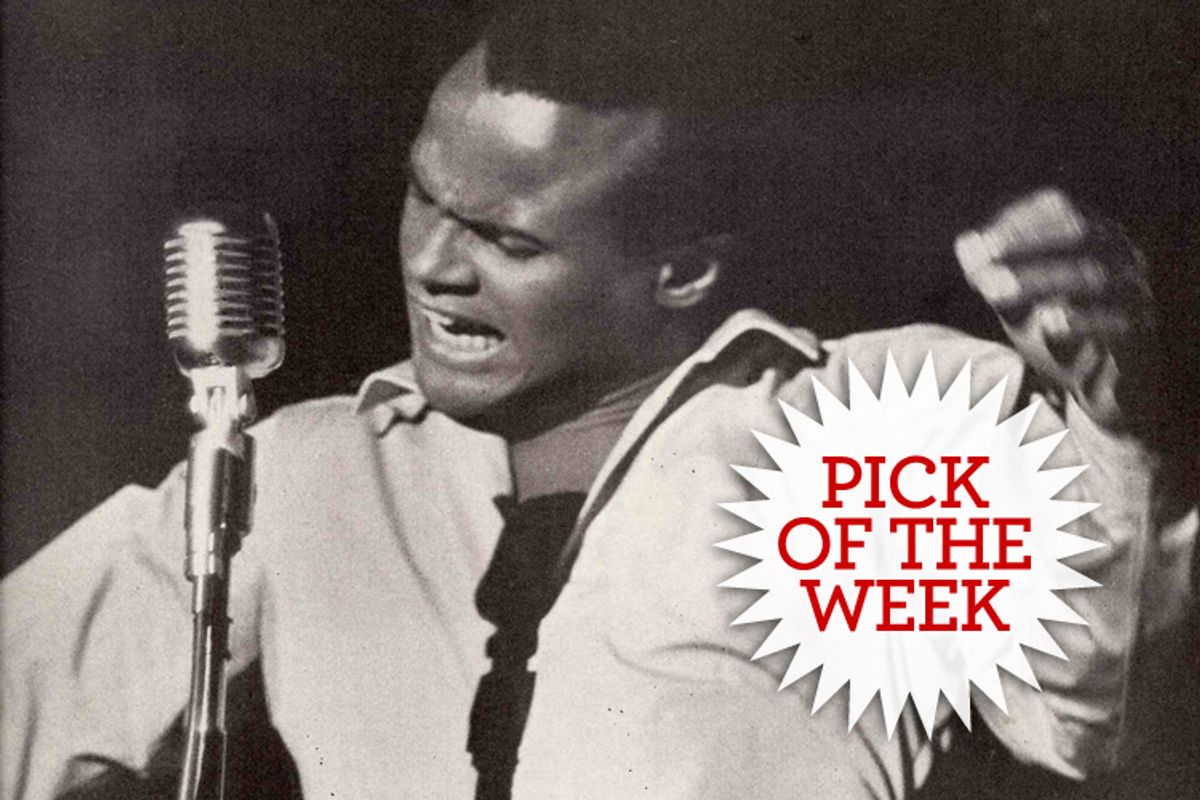

One thing Rostock's film makes abundantly clear is the fact that Belafonte had the opportunity to become a high-profile and sometimes strident social activist because his first incarnation as a celebrity was about as wholesome and non-polarizing as a black man could possibly be. Born in Harlem but largely raised in Jamaica by his grandmother, Belafonte ultimately brought the island's folk songs back to America as mid-'50s pop-calypso hits like "Matilda," "Man Smart (Woman Smarter)" and of course "Banana Boat Song," which you've definitely heard even if you don't know what it's called. (Irrelevant footnote: Belafonte's story speaks to me personally in all sorts of ways, but partly because it parallels that of my own father, who was born in the same month of 1927 a few dozen blocks to the north, and then was sent back to his own grandmother on a somewhat colder island.) With his trademark tight pants and unbuttoned shirt, the muscular Belafonte became a sex symbol to millions of white women and girls at a time when interracial marriage was still impossible in many states, and toured with a mixed-race folk group to cities where black audiences had to watch from the balcony.

I realize this is stretching a little, but Belafonte in the '50s -- viewed strictly as a cultural archetype -- was something like an early version of Obama, an articulate and handsome light-skinned African-American who spoke standard English better than most white people did. (To this day, Belafonte's pronunciation of the word "theater" is redolent with cultural specificity; he says it as Bette Davis or Lynn Redgrave would have.) But as Belafonte himself explains it in the film, his path to stardom was at least partly calculated. Near the beginning of his performing career as a folk singer, he remembers, his idol Paul Robeson came to see him backstage at the Village Vanguard and told him: "Get them to sing your song, and they'll want to know who you are."

If anything, "Sing Your Song" may convey the impression that Belafonte's career as a pop singer and stage and film actor -- a shameless ham, it must be said -- was simply a means to an end, a tool to be used against Jim Crow and apartheid and other forms of racism and injustice around the world. While I suppose it's true that Belafonte's close working friendship with King, or his later relationships with Nelson Mandela and Jean-Bertrand Aristide, may weigh more in the scales of history than "Banana Boat Song," he honestly may be selling himself a little short. Sure, some of Belafonte's calypso numbers may be cheesy, but he was a generous singer with a huge spirit, who pioneered multiculturalism and "world music" long before anyone used those words. The performers he introduced to mainstream audiences included Odetta, Nana Mouskouri and, most famously, Miriam Makeba -- and his 1962 album "Midnight Special" featured a then-unknown harmonica player named Bob Dylan. (In the movie, you'll watch him perform "Hava Nagila" on network TV in 1959, which became part of his concert repertoire for years. You can think that's silly or think it's awesome; I vote for both.)

Belafonte's early association with Robeson (who was without doubt a communist) will raise in some viewers' minds the long-cherished right-wing assumption that Belafonte was or is a treacherous Red seeking to destroy the American way of life. Even bracketing the fact that the two things are not connected -- most American communists were not traitors, just as most American Muslims do not support terrorism -- the evidence is pretty thin. Even the right-wing investigative site Discover the Networks can go no further than claims that Belafonte was "aligned with the Communist Left" and that he "views America as an evil and profoundly racist nation." Depending on your definition of "evil," those vague and disputable terms could be used to describe all kinds of people, from Cornel West to Noam Chomsky to Roger Ebert (to me).

"Sing Your Song" never addresses these allegations directly, other than sourcing most of the FBI's files on Belafonte to a shadowy figure named Jay Richard Kennedy (aka Samuel Solomonick), a one-time Communist Party insider turned showbiz executive and government informant. Kennedy was Belafonte's manager for several years -- while his wife served as Belafonte's therapist! -- and the two of them apparently fed the FBI some ludicrous "Manchurian Candidate" line about Belafonte being a double agent "controlled by Peking." My Internet searches suggest that at least one academic is trying to write a book about Kennedy/Solomonick, and I can't wait to read that one.

I don't support everything Belafonte has ever said or done, but he's a hugely important American dissident who's been on the right side way more often than the wrong one, and who pioneered a path followed by many other activist celebrities, from Marlon Brando to Sean Penn and beyond. Even in this carefully staged self-portrait, we meet a man in his 80s who is aware of his failings as a husband and father (although his two youngest children, David and Gina, helped produce the film) and plagued by the thought that all his labors against tyranny and injustice have not nearly been enough. On one hand, he comes off as boundlessly optimistic, seeking to hand off the torch of rebellion to a new generation; on the other, since the 1980s he seems to have hardened and grown less tolerant of politics. He declined to attend Mandela's inauguration as president of South Africa because of his rift with Bill and Hillary Clinton, and declined to attend Coretta Scott King's funeral because Bush would be there.

With his physical health precarious, Belafonte keeps touring the globe, meeting with European hip-hop artists, L.A. gang members, prison inmates, Native American leaders and his own council of African-American "elders," in search of some resolution or program that might reverse the global tide of neoliberal capitalism and pseudo-democratic police states. He's a hero, all right, but not the kind who gets to ride triumphantly into the sunset at story's end. More like the hero of a long-running tragedy, the kind of hero once summarized this way by the English socialist William Morris: "Men fight and lose the battle, and the thing that they fought for comes about in spite of their defeat, and when it comes turns out not to be what they meant."

"Sing Your Song" opens this week at the IFC Center in New York and the Playhouse 7 in Pasadena, Calif. It opens Jan. 20 in Santa Fe, N.M.; Jan. 27 in Portland, Ore., San Francisco and Seattle; Feb. 3 in Denver; Feb. 10 in Albuquerque, N.M., and Bellingham, Wash.; Feb. 12 in Montgomery, Ala.; Feb. 17 in Hartford, Conn.; and March 16 in Minneapolis, with other screenings and venues to be announced.

Shares