Sir Henry Solomon Wellcome died in 1936, but his curiosity about human understandings of "the preservation of health and life" -- carried forward in the 21st century by the Wellcome Trust -- is supremely infectious.

Open "The Art of Medicine: Over 2,000 Years of Images and Imagination" (University of Chicago Press, out now), which spotlights works from London's Wellcome Collection, and you'll find illuminations from late medieval medical manuals; 18th-century anatomical waxworks with removable organs; leaves from hand-colored plant and herb guides; early-20th-century lithographs advertising gout remedies; astonishing close-ups of implanting human embryos; and much, much more. The collection is so wide-ranging and diverse as to defy a pithy explanation -- but taken as a whole, it's transfixing.

Emma Shackleton, one of the book's co-authors, answered a few of my questions over email; the accompanying slide show offers a whirlwind tour of the past few hundred years of medical imagery.

Roughly how many of the images featured in the book do you think were originally conceived by their creators as "art"? How much of the material was intended simply to be instructional?

For the historic works, we often do not know what the creators’ original intentions were. In making the images, they each would have been working within their own stylistic and cultural traditions. So, for example, anatomical representations made in Persia and Asia would have been created in line with particular traditions, in contrast to those of, say, 15th-century Europe, where the artists of "The Apocalypse" would have drawn on existing images in order to create the Organ Man [slide 1], and his accompanying anatomical figures.

There are many images in this gallery that do instruct and inform, yet, even where this is their primary role, they were often made by highly skilled artists and were valued for their artistic qualities too. In the 16th century, for example, Charles Estienne wrote of the aesthetic pleasure to be gained from studying the human anatomy, while Andreas Vesalius commissioned the engravings of his revolutionary book, "On the Fabric of the Human Body," to be made in the great artistic center of Venice. Their work was appreciated not only by practitioners, but by lay people, too.

However, art relating to medicine has been made for many audiences, and it is the breadth of these perspectives that we were keen to explore and bring together to offer a compelling journey into the landscape of medicine. Some objects and images played a role within spiritual ritual or religious practice; others were made as artifacts intended to protect health or cure disease, as caricatures, as narrative paintings or as contemplative pieces that reflect on personal experiences or medical developments.

Do scientists and doctors today go to the same efforts as their forebears to make graphics, charts, tools and records aesthetically pleasing? How have values changed in this regard?

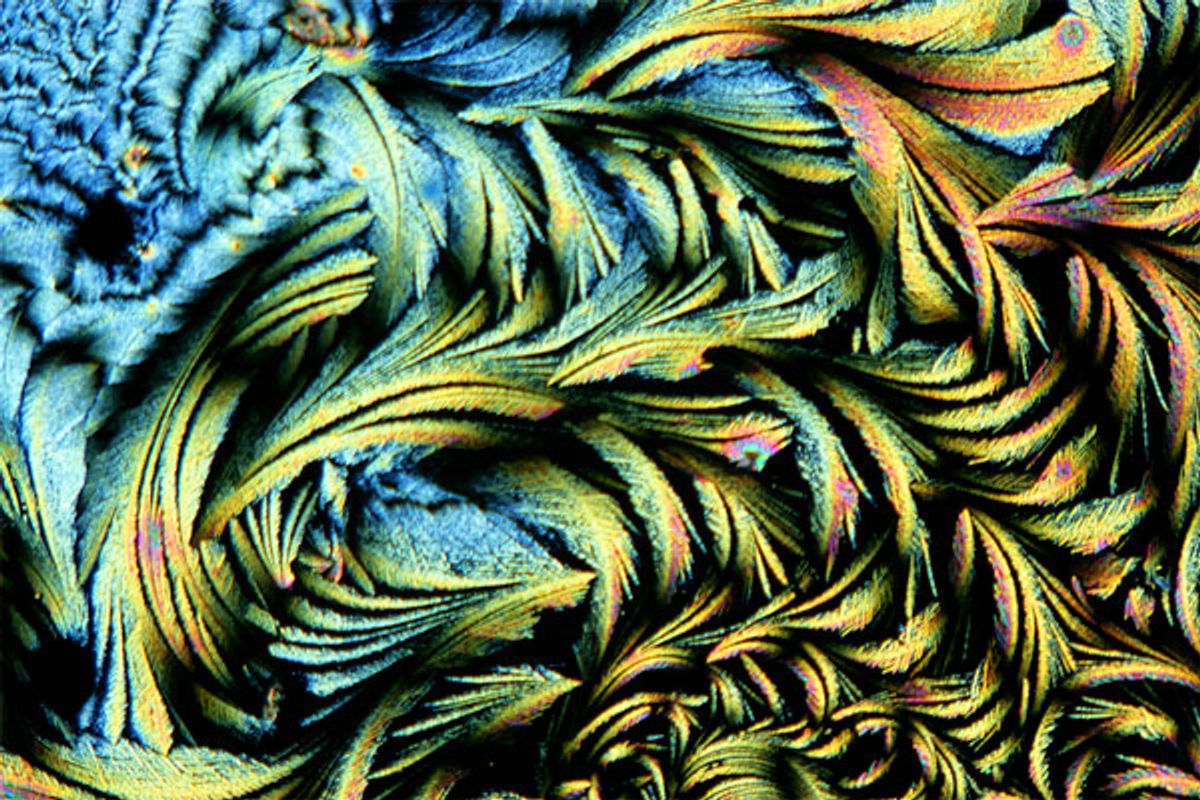

There is a strong tradition of the sciences and art being intertwined, and this continues. The artist Annie Cavanagh has said of the work she creates with microscopist David McCarthy [slide 9]: “It makes an idea concrete or solid, whereas interpretation of literature can go many ways.” Perhaps their extraordinary micrographs highlight one of the major changes in the visual images that are created today.

In the hands of scientists and practitioners like Annie Cavanagh and David McCarthy, we now have remarkable insights at a microscopic level into the body (so we can gain, say, a view of a blood vessel rupturing or neurons in the brain), of the appearance and actions of viruses and diseases, and the structure of medication. Such images can instruct and inform, yet they also give an aesthetic pleasure and reward the curiosity of a lay viewer.

What do you think is the single most powerful thing the collection says about the progress of medicine over the course of the periods it covers? What's the most powerful thing it says about the progress of art?

It is interesting that you ask about progress. For me, the most powerful message the collection came to say was one about continuity. This eclectic collection does span major developments in medicine, diverse art practices and many perspectives from different cultures. Yet at the heart of it is the human body, and while we are each individuals across time and location, personally and within our cultures we have had to find ways to understand our bodies and ourselves in sickness and health. So, for me, at the core is a message about the human condition -- and that is a thread connecting the past, present and future.

Do you have a single favorite image (or a favorite section) from the book? Is there something in particular you think readers might be surprised by?

I hope you don’t mind if I choose a favorite quality. It is that the images allow us to go on fascinating journeys to explore many strands of medicine across time and place, be they anatomy, medical or surgical practice, disease or medication. Follow the trail of herbal medicine, for example, and the images take us from 15th-century Europe to Japan and 19th-century Tibet, or explore astrology in medicine, and we can see visions of its practice across Europe, in Persia, Asia and Mexico.

Shares