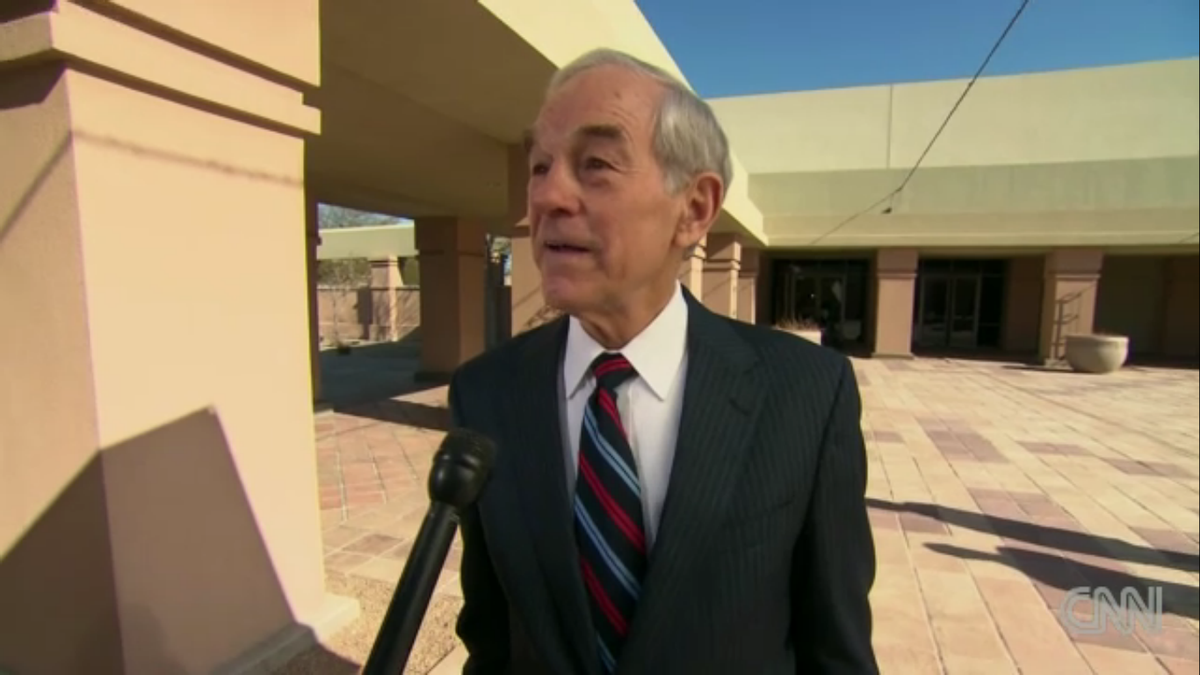

Ron Paul, fresh off a last place finish in Florida with just 7 percent of the vote, made a thoroughly unsurprising declaration on Wednesday: He's not going to drop out of the Republican race any time soon.

"If we continue amassing delegates, we’ll keep going until it’s very obvious," he told CNN's Joe Johns. "But to think in the next week or two all of a sudden there’s going to be a declaration of who’s going to be the winner – I don’t think that’s likely to happen. So I’ll likely be in the race after that.”

To be fair, it's not like Paul was expecting to fare well in the Sunshine State. He spent little time and even less money there and has long been targeting a series of small and mid-size state caucuses, where the grass-roots energy and organizing of his supporters can have a more measurable effect on the outcome -- and where he may be able to catch his opponents sleeping. The first test of this phase of Paul's campaign will come this Saturday in Nevada, whose caucuses Mitt Romney won in a runaway four years ago (with Paul finishing a very distant second).

There's reason to suspect Paul will perform better this time around (although the very limited polling data that's available suggests he's running about where he did in '08), but even if he does, it probably won't have a big impact on the GOP race. Because if Iowa and New Hampshire (and the months leading up to them) demonstrated conclusively that Paul dramatically expanded his base of support between 2008 and 2012, the weeks after those two contests have confirmed what seemed likely all along: He and his army still exist too far beyond the Republican mainstream to wage anything more than a niche campaign for its presidential nomination.

There's no denying the impressiveness of Paul's showings in the lead-off GOP contests. He netted 21 percent in Iowa (more than double his 2008 total) and came within a few points of winning the state outright. And in New Hampshire, he grabbed 23 percent (almost triple his '08 number) and had second place all to himself.

But in both states, he benefited from some very specific factors that just don't exist in most other primary season venues, not the least being months -- years, really -- 0f lead time. Iowa's low-turnout, activist-oriented caucus environment was another help, as was the state's first-in-the-nation status, which made for a crowded field that put any candidate who could attract 20 percent of the vote in striking distance of victory. New Hampshire was friendly turf to Paul because of the large number of independents who participate in its primary and because the state's quirky GOP universe is unusually secular and independent-spirited, with some real libertarian and isolationist pockets.

What happened next is telling, though. A conventional candidate would probably have been able to roll Paul's Iowa and New Hampshire breakthroughs into the next contests. But Paul's support in South Carolina, where he finished with 13 percent, only grew modestly, and the 7 percent he won in Florida isn't much different from his '08 level. Yes, it's true that Paul didn't put up much of a fight in both states, but that's just the point: The characteristics that defined those contests are far more consistent with the characteristics that define most GOP nominating contests than Iowa and New Hampshire -- larger, more ideologically cohesive voting universes, with fewer opportunities to distort the results with a grass-roots campaign and a real need for television advertising.

In New Hampshire, nearly half of the ballots cast in the GOP primary were by self-identified independents, with Paul winning 31 percent of votes -- more than double the level of support he won from self-identified Republicans. By contrast, in Florida, a closed primary state, 80 percent of the ballots were cast by self-identified Republicans, a group that gave Paul just 5 percent. He did much better among self-identified independents (16 percent), but they only made up 18 percent of the electorate.

More telling, perhaps, is another finding in Florida's exit poll: 56 percent of voters said they made up their minds in January. But almost none of them -- a grand total of 3 percent -- broke for Paul. Instead, they went for Romney (45 percent), Newt Gingrich (34 percent) and Santorum (17 percent). What's striking is that Santorum barely registered in polls for all of 2011; without his Iowa breakthrough on Jan. 3, there's no way that nearly one in five Floridians who made up their minds in January would have suddenly decided to vote for him. It wasn't nearly enough to make him a contender in the state, but his Iowa victory clearly translated into more support in subsequent states. But even though Paul won plenty of attention from his Iowa and New Hampshire breakthroughs, virtually no Floridians decided to give him a fresh look. He did far better (11 percent) among those who said they made up their minds sometime in 2011. This is as clear an expression as you'll find of the unique ceiling that Paul faces within the GOP.

What's happened to Paul in South Carolina and Florida will keep happening to him in big, delegate-rich states as long as he stays in the race. Too much of his appeal exists outside of the Republican Party, and too many GOP primaries are decided by large electorates of party loyalists. And even if his caucus strategy succeeds and he nabs (say) a few hundred delegates, the circumstances under which this would give him any real leverage at the convention are very limited. If Gingrich were somehow to revive his campaign on Super Tuesday, run off a string of spring victories and force a deadlocked convention, then obviously any Paul delegates would be hugely important. But otherwise, it'll just mean that Paul has a decent cheering section, assuming he's allowed to speak.

As I wrote after his big night in New Hampshire, Paul and his army are a big story for a lot of reasons. But the idea that he might win the GOP nomination was never one of them.

Shares