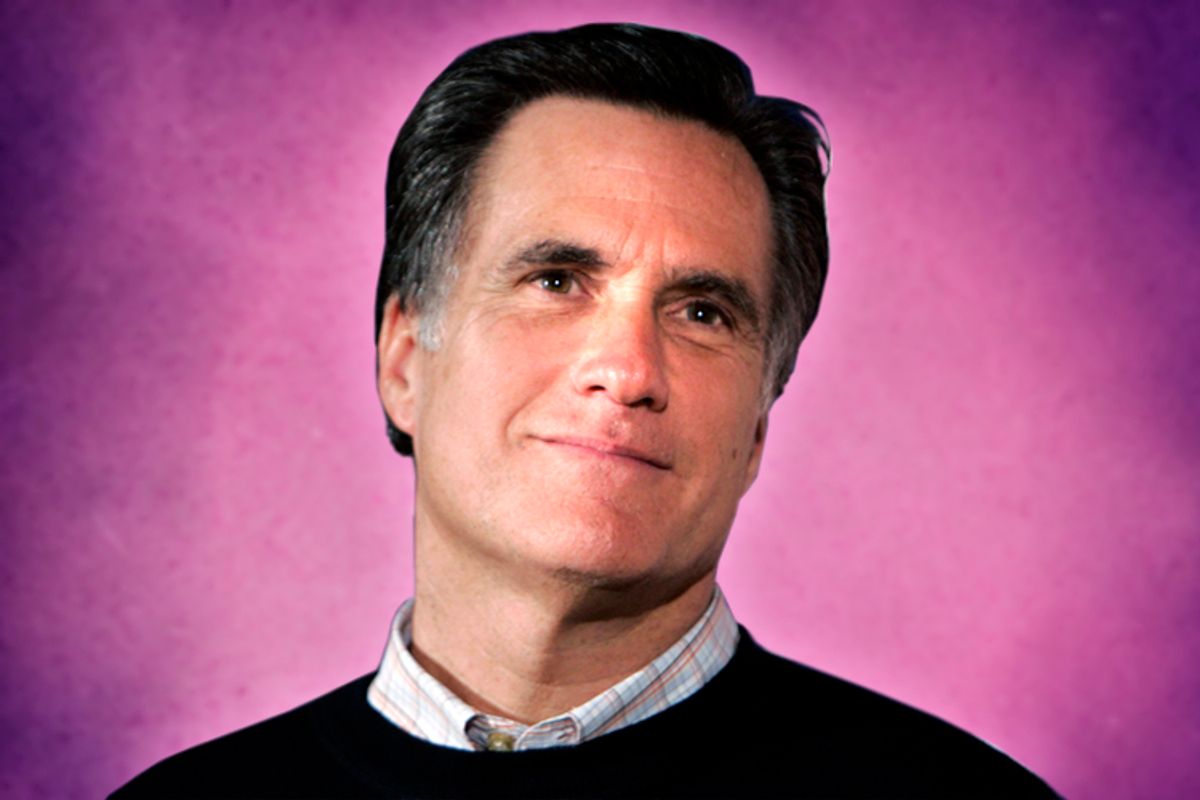

If there is one single impediment to Mitt Romney’s campaign, it is his utter inscrutability, his perplexing failure to schmooze with voters. Romney is seen by many as hollow, robotic, as stiff as his hair-sprayed coiffure.

But to me, Mitt Romney isn’t stiff. He’s just a Mormon.

I know, because I grew up in Ogden, Utah, a city of about 83,000 people, 60 percent of whom are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (I’m not one.) Though Romney was raised in suburban Detroit, he seems a product of Ogden’s Mormon milieu — a town lodged firmly in the 1950s, where homeowners leave their doors unlocked at night, teenagers cruise the boulevard, or “vard,” on weekends and packs of Mormon men comb the neighborhoods after windstorms to clear away fallen branches.

Like Romney, with his habit of saying “gosh,” the Mormons in my high school subbed their curse words — hell was “heck,” anything stronger was “fudge” or “freak.” Romney speaks with the classical Mormon accent, dropping his t’s and g’s, turning “Washington” into “Washinton” and “enterprise” into “enerprise.” He even dresses like a Mormon, wearing the dark suit, white button-down shirt and red or blue tie of the return missionary, or “RM” in Utah parlance. And while Romney may not stand out from the Republican pack for his sartorial taste, to any Mormon he is riffing on the missionary motif.

Romney vacillates when it comes to talking about Mormonism on the campaign trail, alternately playing it down as a private matter and emphasizing his devotion to his “faith” like he did in a recent advertisement, without specifying which faith that is. But make no mistake, Romney is a man steeped in Mormonism — a religion that is not so much a belief system as a lifestyle, urging its adherents to be “in the world but not of the world.” Romney, in fact, is the archetypal Mormon male.

In Mormonism, gender roles are highly prescribed. Mormon men define themselves in contrast to women but also against other men in the secular world. While the “natural man” is prone to anger and sexual urges, the Mormon man is a picture of loving restraint — LDS homes are filled with paintings of Jesus surrounded by lambs, women and children. Any Mormon man worth his salt knows by heart the following line from "Doctrine and Covenants," the tract written by Mormon prophet Joseph Smith while he was a prisoner in Liberty, Mo., in 1839: “No power or influence can or ought to be maintained by the virtue of the priesthood, only by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned.” For Mormon men, wrote David Knowlton in his seminal 1992 article on LDS masculinity in the Mormon Sunstone Magazine, “a measure of spirituality also becomes a measure of manhood.”

The very qualities that make a good Mormon man, however, make for a poor campaigner. Up until mid-January, Romney was widely seen as too timid to respond to Newt Gingrich’s barbs, letting his super PAC do it on his behalf. Romney’s reluctance may have something to do with his faith — Mormon men are taught to be specific in their criticisms and to follow them up with “an increase of love of him whom thou has reproved, lest he esteem thee to be his enemy” as written in "Doctrine and Covenants." Romney’s transformation into a political assailant won him Florida, but it might have cost him spiritually. Even the new Romney seems a bit squeamish on the attack, ending each swipe in the Republican primary debates with a tight-lipped smile.

“I don’t think politics is a natural place for Mormon men,” said Richard Bushman, a prominent Mormon historian. “To go into a political scene, where you have to have a hard edge and knock heads and attack, that is going against the Mormon grain. I cringe when I hear Mitt talking that way. That is not the way he ought to be as a Latter-day Saint living this other ideal.”

Central to Mormon masculinity is the priesthood, a role given to all worthy, church-going Mormon boys at the age of 12. Because the LDS church is both a patriarchal church and a lay church, it invests deeply in training boys to remain devoted Mormons in adulthood, endowing them with prepubescent responsibilities like speaking in front of their congregations and collecting donations on behalf of the poor. Mormon boys at the ages of 12, 14 and 16 are called, respectively, deacons, teachers and priests — titles that in other religions belong to adults. When a Mormon embarks on a mission, he becomes an elder, like Romney did, at the tender age of 18.

Because of the priesthood, Mormon men exude a kind of humble authority that might strike other people as disingenuous. When Newt Gingrich told Romney to “drop the pious baloney” at a New Hampshire debate in January, he might have been responding to what one skeptical Mormon I spoke with called the “pseudo unction” of the Mormon male personality, the gentle hubris that comes with being raised without a shred of spiritual self-doubt.

This might explain why Romney has a certain Teflon quality. Romney has made U-turns on abortion policy, global warming and the nationwide application of his Massachusetts healthcare plan. But in contrast to Sen. John Kerry’s 2004 campaign for president, criticism of Romney as a flip-flopper hasn’t seemed to stick. Romney might be pandering to the Republican hard right, but it’s not always easy to detect — he speaks with that preternatural self-assuredness common to LDS men.

“He makes no big mistakes in the way he says something,” said Becky Johns, a professor of communications and women’s studies at Weber State University in Ogden. “He may make a lot of mistakes in the content of what he says. But he will never do the big dramatic display of any kind. Even his smiles are measured to be quite moderate.”

Throughout Romney’s campaign, he has been dogged by the perception that as president he would answer to the Mormon leadership — an assertion he denied in his 2007 speech “Faith in America.” But, according to University of Utah Mormon historian W. Paul Reeve, questions over Romney’s spiritual obligations to Salt Lake City overlook the fact that Mormonism is not solely authoritarian in nature. Mormons adhere to church law, but they also have a say in their spiritual fate through the concept of “revelation.”

“This notion that Mormons are sort of one-dimensional automatons waiting for the signal from Salt Lake City is ridiculous,” Reeve said. “It is the balance between the heart and the mind that can govern the notion of seeking guidance from God.”

Both Mormon men and women are capable of receiving godly revelation for themselves or on behalf of their families — said to come in the form of a “still, small voice” or a burning feeling in the chest. But only Mormon men in leadership positions can receive revelation on behalf of other people. In the '80s, Romney served as a bishop over a Belmont, Mass., congregation, and later as stake president over a group of congregations in the Boston area. In both of these roles, he was capable of revelation for his laity.

Romney’s spiritual leadership, however, was challenged at times. As bishop of the Belmont ward, he clashed with a group of Mormon feminists; one of them wrote an essay in the LDS women’s journal Exponent II saying that a local leader — later revealed to be Romney — counseled her against terminating her pregnancy, even while she had developed a dangerous blood clot. Though Romney said he did not remember such an incident, he conceded that as bishop he advised women against abortions except in rare cases — following the church’s official policy.

As president of the United States, Romney has promised not to hew to church policy like he did as a Mormon lay leader. “Let me assure that no authorities of my church, or of any other church for that matter, will ever exert influence on presidential decisions,” he said in 2007. “Their authority is theirs, within the province of church affairs, and it ends where the affairs of the nation begin.”

Taking Romney at his word, there are still questions about the way that Mormonism has shaped him as a leader. Namely, what does it mean to be president if you believe you are in this world but not of it?

Shares