Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping’s visit to the United States comes at a contradictory time in clean energy relations between the two countries. On the one hand, significant progress has been made under the clean energy cooperation agreements signed by Presidents Hu Jintao and Barack Obama in the fall of 2009. On the other hand, the two countries may be on the verge of a clean energy trade war. As a result, the positions that Xi and Obama take on these issues over the next week may well set the tone for that relationship’s future, for better or worse.

China and the United States have launched numerous energy cooperation initiatives during the past 30 years. Only over the past decade, however, have they become global leaders in the relevant technologies, both as users and manufacturers. China now leads the world in wind power deployment, followed by the United States. Chinese investments in clean energy exceeded those of any other country in both 2009 and 2010, but the U.S. was back to No. 1 in 2011 (where it had been for several years prior to 2009).

The seven new bilateral clean energy initiatives launched in 2009 focused on key areas, including renewable energy, advanced coal technology, energy efficiency and electric vehicles. The US-China Clean Energy Research Center (CERC) (a virtual center that sponsors work in several locations in both countries) in particular has established a new model for cooperative clean energy research, development and demonstration that spans the public and private sectors and involves top researchers from universities and national laboratories in both countries. These programs have propelled numerous other collaborations, some of which — if the two sides decide to emphasize clean energy cooperation over competition — may be included in major announcements during Xi’s visit.

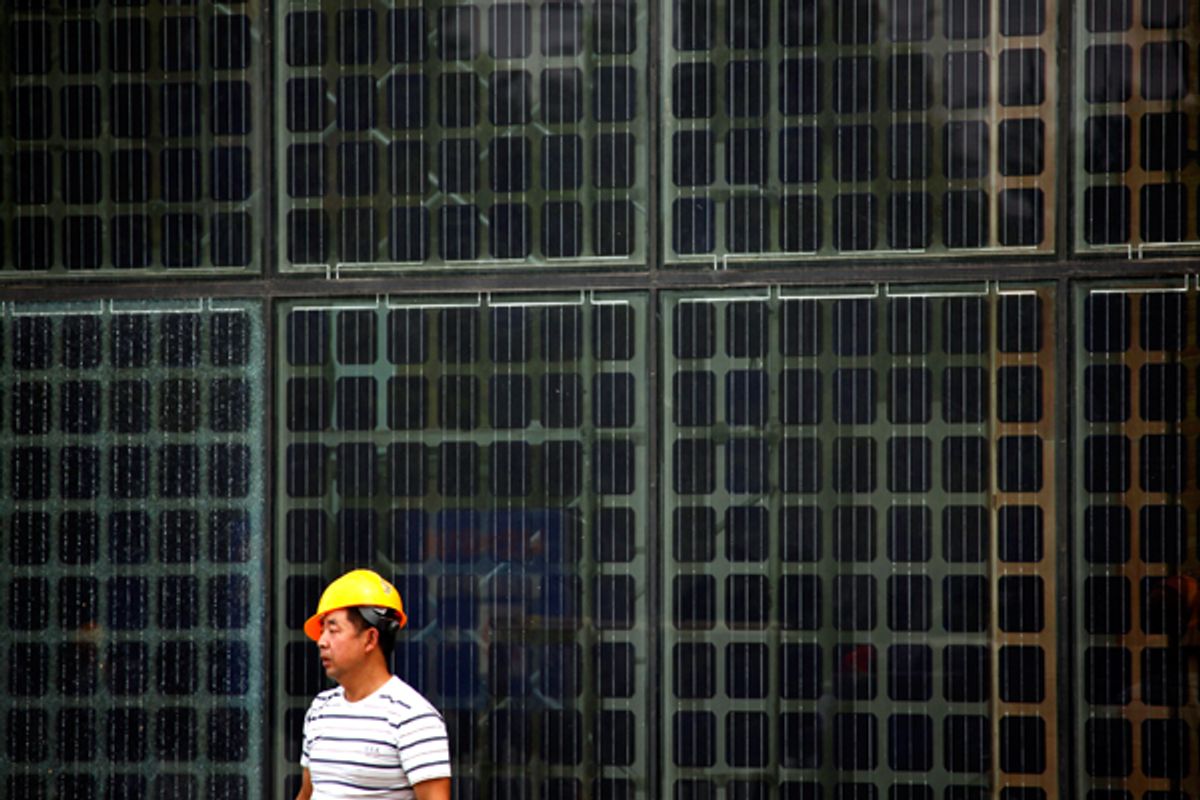

However, at the end of last year the United States initiated antidumping and countervailing duty investigations into China’s practices in the solar and wind sectors, and the Department of Commerce will decide soon whether to impose duties on Chinese solar panels and wind turbine components. In the meantime, election year politics and a slow economic recovery are fueling competitive tensions.

President Obama announced in his State of the Union address last month that he would establish a new trade enforcement unit to speed investigations of unfair trading practices by China. Beijing has (not surprisingly) responded with its own investigation into American clean energy support programs. This comes as the U.S. renewable energy industry is increasingly divided over China’s role. For example, the Coalition for Affordable Solar Energy (a U.S. solar industry association) has asked the Coalition for American Solar Manufacturing (another U.S. solar industry association) to drop its petition that launched the solar panel investigation. A CASE report estimates that higher U.S. import duties on Chinese solar panels will eliminate up to 60,000 American jobs and hurt U.S. consumers even more than U.S. producers.

We are entering a period in which the incentives for conflict may overpower the incentives for cooperation. China and the United States are the world’s two largest economies, and should be leaders in establishing and enforcing the rules of the global trading system. But as the largest producers and consumers of energy, as well as the largest greenhouse gas emitters, they also have a responsibility to develop domestic, clean and affordable sources of energy for themselves as well as for others.

Both nations recognize the vital importance of strengthening innovation systems to inspire economic competitiveness, and both are increasingly becoming the leaders of the clean energy industry. These technologies are global industries with global supply chains, however, and national technology providers increasingly are crossing borders for both innovation and production. Our leaders would be well served to focus on how the two nations can work together to develop crucial energy technologies for the future, rather than on how to create even more obstacles.

Shares