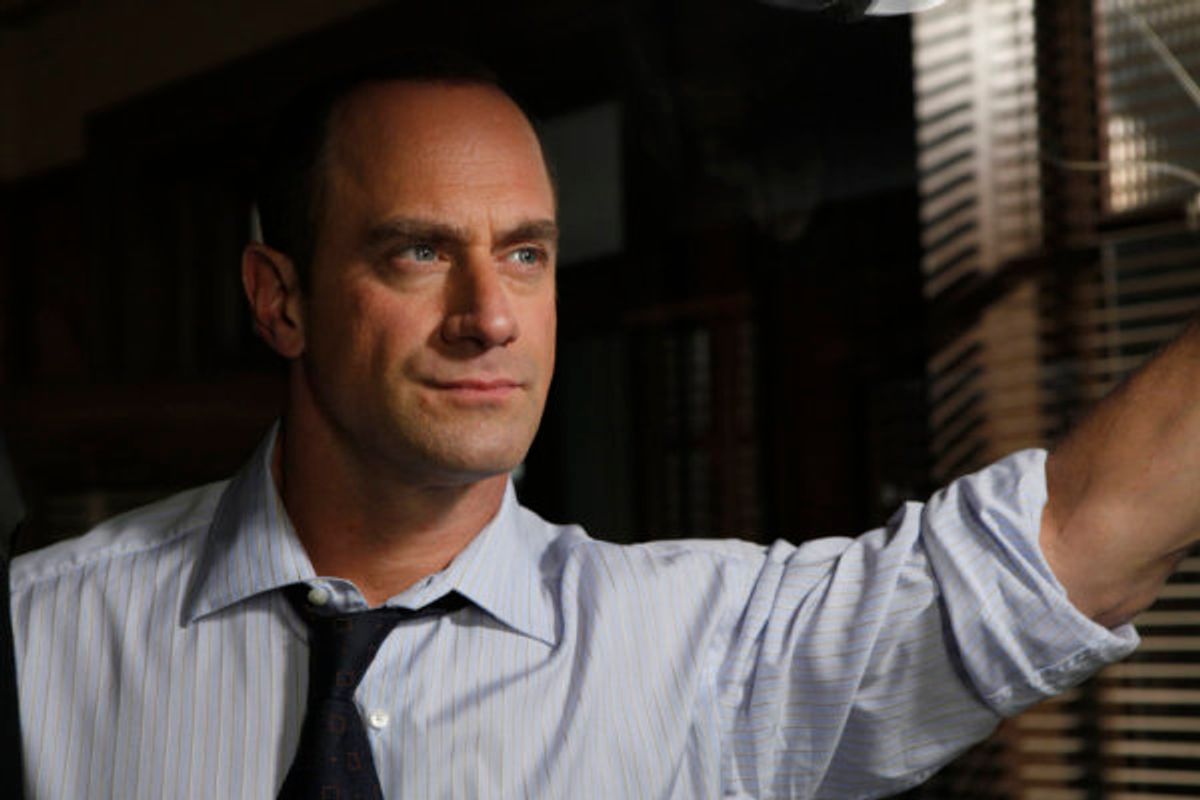

People always want to know how you got a certain disease. They’re thinking of themselves, of course — the sore throat, the odd bruise on the wrist, that lingering cough. But people are surprised when I tell them how I discovered I had Parkinson's. I was watching "Law and Order: SVU."

I had flipped on a rerun, which I do when I’m tired and bored. It's better than reality TV, and it's reliable. There’s always an episode of "Law and Order" playing somewhere.

I’d seen this one before, so I was paying minimal attention. I flipped through a magazine. A man, shaking badly, was telling the detectives about his disease, Parkinson’s. Years ago he’d started having symptoms. He listed them.

I put down the magazine. A chill ran up the back of my neck. I had every single one.

Why hadn’t I suspected anything was wrong until then? Easy. I had found a way to explain away every problem I encountered. My car key didn’t open the door without a struggle? It must have gotten bent somehow. My can opener didn’t work anymore? Ditto. My favorite cutting knife couldn’t seem to do the job right? Fine, I’d replace it one of these days. What did any of this have to do with me?

There was one thing that did, though, and it puzzled me — my right arm didn’t swing anymore when I walked. It wanted to bend itself at the elbow, jutting out stiffly. I wondered about that one, even mentioned it to a friend, a longtime nurse practitioner. She chalked it up to another manifestation of my long-term back problem. I figured it might be punishment for the way I gripped my computer mouse.

Only now, the man on the show explained issues that were all too familiar -- he had a stiff arm, too, and difficulty with the simplest motor skills. And more: exhaustion, odd aches, a suddenly clumsy gait.

And hearing him, I knew. I knew with a rare clarity. The clean pop of a ball into a glove: connection complete. I called no one. Tomorrow I’d search the Internet; tomorrow I’d find a neurologist. But none of that was strictly necessary, not for diagnosis, anyway. Finding the specific traits on the Internet the following day, hearing the neurologist confirm it a few days later -all of that was anti-climatic. Sitting there, watching that damn rerun, I knew the truth: I had Parkinson’s.

Everyone knows something about Parkinson’s, thanks to Michael J. Fox. It’s a progressive neurodegenerative disease that involves shaking, rigidity, weakness. What I hadn’t known was that apparently Parkinson’s can affect your mind, too.

“Any problem with word retrieval?” asked the neurologist the first time I saw him, his eyes sharp with interest. Well, sure, I had some now and then, like everyone who is over 60. I dismissed it, airily.

“Any problem with word retrieval?” asked the neurologist the second time I saw him. What was this, a mantra? Again, I said calmly I was doing fine. As a matter of fact, better than him. He was not all that young himself, and an extremely slow talker. Several times I found myself filling in words for him; a couple of times, analogies as well.

“Any problem with word retrieval?” asked the neurologist the third time I saw him. This was beginning to grate. Was it supposed to be some kind of hypnotic suggestion? If you ask something enough times -- in a paternal tone of voice, eyes twinkling expectantly, with a distinct aura of anticipation -- well, hey, aren't you going to end up causing it? No, no problem, I said.

That week, I received a long form in the mail for a movement disorders clinic where I had an appointment. It chilled me. Are you able to turn over in bed by yourself / with help / not possible. Are you still able to form sentences (usually/rarely/never). Can you swallow?

Has anyone in the field ever heard of the tyranny of low expectations? Personally, I don’t appreciate these hints, if that’s what they are, that I’m about to descend into mouth-foaming dementia any minute.

Michael Kinsley had a long piece in the New Yorker a few years ago, which dealt with his Parkinson’s. (He’s had it 20 years; he still seems, against all odds, to have plenty of words at his disposal.) He was enthralled by one of the side effects mentioned in the literature, an urge to take up gambling. I haven't gotten that one myself, but not long after I dumped the first neurologist, I was intrigued by a book in my new doctor's office, "How to Win at Poker."

“And what is this?” I challenged him when he finally showed up. (He had the grace to blush, insisting a patient must have left it.)

This neurologist doesn't bring up the cognitive issue, but he does make sure one of his associates gives me the test every time I drop by.

Not heard of the test? Obviously you’ve never had a relative with Parkinson’s or Alzheimer's, like my dad, who died of that latter disease 10 years ago. It’s the same test they gave him at each appointment. You're told to draw a clock, poised at 10 after 11. You're told to count backward from 100 by sevens, list all the words you can think of starting with an F. (After a few go-rounds you stop trying to avoid the obvious ones -- what the hell.) Most irritatingly, you have to remember five disconnected words for five minutes, then spew them back.

I decided to engrave the words (they’re always the same ones) on my brain. And it worked. I may eventually forget the date, the current president, the names of my grandchildren. But what I will never forget -- I’ve made sure of that -- are those five words, which I generously pass on to anyone with similar concerns: red, velvet, face, church, daisy.

Six months after my initial test, when the associate told me she was going to give me five words, I interrupted her and reeled them off. She was suitably impressed. A year later, accompanied by an intern, she had me do it again, which I did, feeling a bit like a circus seal. Would I manage so well if they changed the words? I don't know. But for now, silly as it sounds, this hurdle does make me feel like I’m holding my own. Of course I do other things: take my meds, undergo physical therapy, go to the gym, have intensive sessions with a Parkinson’s exercise guru, even take a few drum lessons. Do what I can, in other words.

Parkinson’s has a lot in common with other neurodegenerative diseases: To be blunt, they don’t really know a damn thing about it. Early on I posed this question to a Parkinson’s specialist: I suffered a fairly serious head injury six years ago. Could that have been the cause?

His answer? A giant shrug. Unfortunately, no one else knows either. The Internet is crawling with possible cures. It's not a week that a friend doesn't send me one. Tincture of marijuana? Lyme disease treatment? Tandem bike riding? Wet battery packs, whatever those are. I appreciate their concern, even if I'm not necessarily up for trying this stuff.

Of course, Parkinson's is an extremely individual disease, different for every case. For some, it can be fast moving and brutal. The mother of one of my son’s friends was diagnosed the same week I was, and can no longer live on her own.

Michael J. Fox, our beloved patron saint, calls himself lucky. I wouldn’t go that far, but when it comes to having Parkinson’s, I know I’m one of the fortunate ones.

It’s been over three years since that "Law and Order" rerun. I get exhausted easily, I move more slowly than I did before, I have various aches and pains. But I’m still reasonably intact, still mobile, and I have a handicapped placard, a true advantage for anyone living in D.C.

Some people prefer to keep medical information to themselves. But when people ask how I’m doing, I tend to blurt out my diagnosis. I can't stand the idea of someone treating this like a deeply unmentionable horror. My candor can lead to confusion sometimes, because people don't understand Parkinson's, though maybe that will dissipate over time. After I told one woman, she later informed a party of people that I was dying.

I’m not, OK? Not even close.

Shares