Alabama, a state not traditionally known for pro-choice mobilization, is in an uproar this week over proposed legislation that, according to news reports, is similar to the controversial Virginia ultrasound-before-abortion bill. One Birmingham Democrat in the statehouse called the bill "a radical attempt to humiliate women," and another said, "To me, it is another form of rape, without a woman's consent." Alabama's governor, recently buttonholed by the Huffington Post, has refused to take a position. The bill's author has promised to make the "transvaginal" part optional, and other states with similar legislation pending are on the defensive about the method of ultrasound, claiming ignorance.

In Alabama, Facebook groups and Change.org petitions in opposition sprung up overnight, proclaiming that Senate Bill 12, the "Right to Know and See Act" will "require all women seeking an abortion to first have a transvaginal ultrasound before proceeding. This procedure is not a medical necessity and merely a political tactic to unnecessarily undermine women's reproductive options."

All true, but there's just one thing opponents have left out, or don't seem fully aware of: Alabama has actually required ultrasounds for abortion patients since 2002. Since the majority of abortions in Alabama, as in other states, take place before eight weeks -- when a transvaginal ultrasound is customarily used for a clearer picture -- thousands of women may already have been subject to this form of state-mandated "rape" for over a decade. That legislation, the 2002 "Woman's Right to Know" act, was challenged in court for other reasons, mostly related to the First Amendment, but eventually upheld. Forced vaginal penetration does not appear to have entered the conversation until the recent uproar in Virginia, using that language, struck a chord. The imagery and subsequent outcry, says Nancy Northup, president of the Center for Reproductive Rights, was "able to shed light on it in a way a thousand legal arguments can't."

In fact, the relatively novel part of the Alabama legislation rests in the "See" part. As it stands now, the bill, which is expected to go before the state Senate sometime this week, requires not only that an ultrasound be performed before an abortion, but also that the technician or doctor "provide a simultaneous verbal explanation of what the ultrasound is depicting, which shall include the presence and location of the unborn child," and to "display the ultrasound images so that the pregnant woman may view them." If the bill becomes law, Alabama will join Texas in having one of the most extreme ultrasound laws in the country -- not because of a forced transvaginal ultrasound, which is actually already commonplace in several states. The latest "pro-life" innovation is the state is forcing a woman to look at an image and, where applicable, listen to a fetal heartbeat with the express aim of dissuading her from her choice.

The pro-choice movement's legal arm, including the Center for Reproductive Rights, couldn't get the earlier Alabama law overturned, though it tried. It has, however, been challenging the Texas law since it passed last year, mostly on First Amendment grounds that the state is mandating ideological speech. But there, it's hit a wall: On Feb. 10, the 5th Circuit, which had upheld the Texas law, declined a rehearing with the full panel. The law is now in full force. There's been more success blocking similar laws in Oklahoma and North Carolina, where litigation is also winding its way through the courts. But taking these cases to their end means rolling the dice at the Supreme Court -- notably with Justice Anthony Kennedy, who in the Court's most recent ruling on abortion, sounded sympathetic to claims of widespread "abortion regret" despite finding "no reliable data to measure the phenomenon." And unproven claims about female regret for lack of "informed consent" are what this ultrasound strategy claims to be all about.

"The fear is that the 5th Circuit decision is going to open the floodgates" to laws that also force viewings and descriptions of ultrasounds, and in some cases impose new waiting periods, said Northup. Given the mixed record of challenges to such laws in court so far, Alabama pro-choicers' best shot seems to be to capitalize on the backlash and try to prevent the bill from passing in the first place. But they'll still have to contend with the Women's Right To Know Act already on the books, as will anyone else opposed to "state-sanctioned rape" in the total of seven states that already have required-ultrasound laws. The question is whether, in a time of heightened grass-roots pro-choice action, any kind of ultrasound law will become politically radioactive. (Even in Virginia, the proposal hasn't gone away entirely; the bill has been modified to only include abdominal ultrasounds, where effective, and a vote is imminent)

- - - - - -

Exactly 20 years ago, the Supreme Court helped open the door to more emboldened "informed consent" laws with Planned Parenthood v. Casey, upholding most of a Pennsylvania law that imposed a 24-hour waiting period, a parental consent requirement, and "informed consent" provisions. Back then, that meant the distribution of written materials as long as they contained "truthful, non-misleading information about the nature of the abortion procedure, the attendant health risks and those of childbirth, and the 'probable gestational age' of the fetus."

The draft legislation offered by Americans United for Life, which has been a major architect of state-level anti-choice laws, relies heavily on Casey, including the paternalistic concern in the decision that women might not know what pregnancy means -- the alleged "risk that a woman may elect an abortion, only to discover later, with devastating psychological consequences, that her decision was not fully informed.”

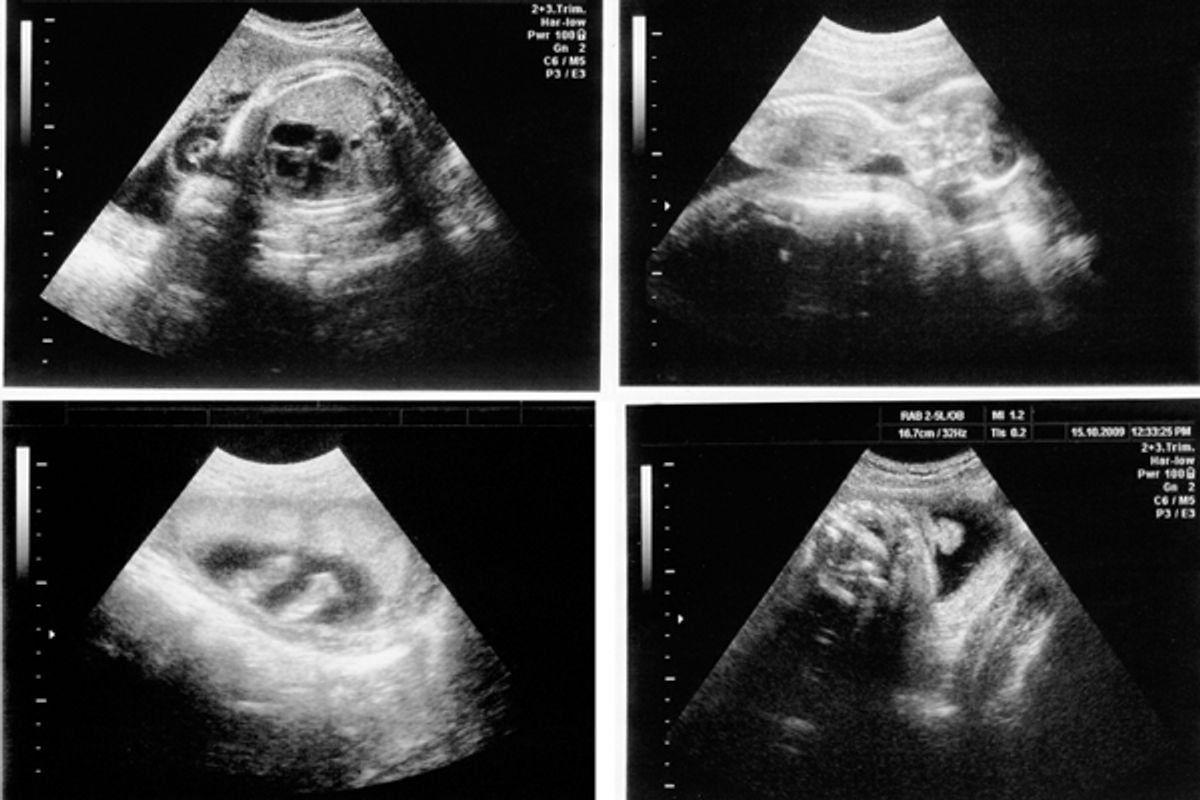

The Pennsylvania law didn't include an ultrasound, but as the procedure has become more broadly available and advanced, abortion opponents have crowed that "technology is on our side." The assumption is that women who have abortions are duped by doctors about what exactly it is that they're terminating, despite the fact that six in 10 women who have abortions have already carried a pregnancy to term. As the executive director of Students for Life of America, put it, “Ultrasound technology has played a big part in helping to make this generation pro-life,” adding, “When you speak to women who had abortions in the 1970s and ’80s, they will tell you that the abortionist told them their baby was simply a blob of tissue ... They can no longer deny that the unborn child is a baby.”

Although some abortion providers choose to perform ultrasounds as a matter of course, the pro-choice movement opposes forced ultrasounds because they override the doctor's discretion and the doctor-patient relationship, in a manner that is not only condescending to the woman's preferred course of action, but also often requires a greater outlay of time, sometimes an entire extra day, as well as money. Not only do they not change anyone's mind, ultrasounds stigmatize and intimidate women who are already under stress.

But with that Orwellian Woman's Right to Know Act boilerplate, in all its pseudo-feminist implications, pro-choicers have been cast in an unenviable position -- at least in the pre-"state-sanctioned rape" terminology landscape. They could argue that no evidence shows that ultrasounds dissuade women from having abortions -- so far, none does -- but that risks inadvertently sounding like they believe the only desirable course is abortion or like they want to keep information from women. Of course, some women have reported seeing the ultrasound and feeling relieved about their decision to terminate, since so many abortions occur at a point in which there is very little to see.

Medical evidence, in any case, has never been the strong suit of the anti-choice movement, although it is astonishing just how flimsy their case for women being swayed by ultrasound technology is. The draft legislation for Americans United For Life claims that “medical evidence indicates that women feel bonded to their children after seeing them on the ultrasound screen.” The only citation is a very short 1983 article by a physician and a bioethicist in the New England Journal of Medicine. This opening sentence gives a sense of the level of research involved in the article, which is less than 400 words:

"We have recently seen two cases in which women in the late first or early second trimester of pregnancy reported feelings and thoughts clearly indicating a bond of loyalty toward the fetus that we and others had associated with a later stage of fetal development."

Again, that would be two cases, both of them in later stages of pregnancy than the vast majority of abortions. One woman is described as a victim of abuse and had an ultrasound to determine whether her abuser had damaged the fetus, and the other was being screened for a genetic anomaly, having already had a child with a genetic disorder requiring surgery. Neither woman is described to have come in explicitly seeking an abortion. The authors, John C. Fletcher and Mark I. Evans, speculated that when it came to possible genetic anomalies and interventions in the womb,

A court-ordered ultrasound viewing would be a potent (and unfair?) maneuver in the hands of those who represented the interests of the fetus in a dispute over proposed fetal therapy. Of course, ultrasound could be used to the same end by those who oppose abortion itself.

The article goes on to muse that "perhaps a new stage of human existence, 'prenatality,' previously only mirrored in poets' and mothers' dreams about the fetus, will be as real to our descendants as childhood is to us ... Of such stuff are many human dreams made." Not quite "medical evidence."

It's not clear whether the authors intended their meditation to fuel this particular obsession of the anti-choice movement. Fletcher committed suicide in 2004. Evans currently makes his living around that foretold "new stage of human existence": He heads a clinic on Manhattan's Upper East Side that specializes in prenatal testing and genetic screening (the same kind Rick Santorum has been recklessly condemning) and Evans' bio says he has won "awards for the protection of women's rights from the National Organization for Women and Planned Parenthood." He is described as "a pioneer in the practice of multifetal pregnancy reduction" -- in other words, abortion of one or more fetuses in the risky instances of multiple pregnancies. The abortion struggle is full of ironies, but the case of Evans, a living example of how ultrasounds can be used for disparate ends, is a rich one. (He didn't respond to a request for comment.)

In the nearly three decades since that article was published, the anti-choice movement realized that it was up against the perception that it cared more about the fetus than the mother, and that it had naturally been pitted against groups that made fighting for women's rights their core principle. They've been co-opting feminist language ever since. Americans United For Life's boilerplate legislation for banning abortion after 20 weeks -- bearing the most misleading name of all, the Women's Health Defense Act -- concedes that

"Unfortunately, some still see legal abortion as a “necessary evil,” bad for the unborn child but good for women (keeping them out of the “back alley” by providing safe abortions).

For this reason, legislative and educational efforts that only emphasize the impact on the unborn are insufficient because they fail to account for this paradigm. The public is concerned about both the impact on women and the impact on the unborn from abortion or from prohibitions and restrictions on abortion."

In other words, by manufacturing a concern about women's health and safety, the anti-choice movement defused middle-of-the-road critics and passed the first round of ultrasound laws and similar restrictions with relatively little fanfare, at least compared to what we've seen lately. And those health and safety concerns truly involved fabrication: While each woman's response to an unintended pregnancy and an abortion varies along a broad spectrum, there is no evidence to indicate that in any meaningful, aggregate sense, abortion actually damages women.

As a Guttmacher report puts it, "Likely because the science attesting to the physical safety of the abortion procedure is so clear" -- several studies have indicated that abortion is actually safer than carrying a pregnancy to term -- "abortion foes have long focused on what they allege are its negative mental health consequences. For decades, they have charged that having an abortion causes mental instability and even may lead to suicide, and despite consistent repudiations from the major professional mental health associations, they remain undeterred." Neither the American Psychological Association (APA) nor the American Psychiatric Association recognizes so-called post-abortion traumatic stress syndrome as grounded in clinical evidence. Even Ronald Reagan's antiabortion surgeon general was unable to produce a legitimate case, concluding, "the scientific studies do not provide conclusive data about the health effects of abortion on women."

Abortion opponents don't much care. The introduction to the AUL model legislation on ultrasounds, which can make its way verbatim to statehouses nationwide, is introduced with the unfounded, and highly ironic, claim that “in the abortion industry, paternalistic attitudes toward women still prevail and, as a result, women continue to be uninformed of the risks and consequences of abortion.”

Women, in this formulation, aren't rational creatures who are making a choice for their own lives and bodies; they are fragile, emotional, subject to pressure, an idea that simultaneously seeks to draw on earlier feminist criticisms of the medical profession and on essentialist stereotypes, while denying women any agency and seeking to actually coerce them. The hoped-for takeaway is that abortion opponents aren't seeking to criminalize women's behavior (or put them in jail for murder, the natural and consistent conclusion of the anti-choice mentality), they're just trying to remind them of the maternal instinct that allegedly lies in every woman's heart.

There's a reason many of these laws have tried to leave the door open for women -- and chillingly, in the case of the Alabama bill, "fathers" and "grandparents" -- to sue doctors for allegedly failing to properly inform them. Something has to reconcile the idea of saving women from abortion-greedy doctors with the fact that so many women willingly choose abortion for themselves. Surely it is because the women were lied to by the doctors, not because of their own complex set of feelings; otherwise, how could they have departed so far from a woman's natural role and "killed" their "baby"?

This has been an effective tack for anti-choicers, not only because of that co-opting of feminist rhetoric, but also because it's coincided with an age of ubiquitous ultrasounds for wanted pregnancies. Not long after the antiabortion movement realized that a poster of a thumb-sucking fetus could get them further than a bloodied one could, sonogram scans that are welcomed proof of fetal development are being enthusiastically posted and "liked" on Facebook. No wonder Focus on the Family has given out hundreds of thousands of dollars, with 536 grants since 2004, for ultrasound equipment at antiabortion crisis pregnancy centers: "As we investigate ways to encourage mothers-to-be to carry their babies to term, we’ve been extremely encouraged to learn that women who see their babies on ultrasound are far less likely to seek abortions than those without access to such an option."

If such centers are indeed seeing results in "encourag[ing] mothers to be" (and you'll have to take their word for it, for what that's worth) it may have less to do with the ultrasound itself than what happens around the viewing. Often masquerading as doctors' offices or abortion clinics with the help of white coats and said ultrasound equipment, they offer factually inaccurate information about the medical risks of abortion and then try to personify the fetus as much as possible. One woman I interviewed who accidentally visited a Brooklyn, N.Y., crisis pregnancy center expressly seeking an abortion described being told, "I think you're going to be a really great mother" and of the ultrasound, "Look how cute!" as she sobbed in confusion. In another first-person account, an ultrasound technician at a crisis pregnancy center offered to type "Hi Mom and Dad!" next to the head of the fetus. (Religious conversion efforts have also been documented.) Crisis pregnancy centers aren't formally involved in the ultrasound-before-abortion process, although they would like to be: Last year, a federal district court foiled South Dakota's plan to force women to visit one before an abortion, but the state's crisis pregnancy centers have won the right to fight back in court. Many already receive taxpayer funds.

Up until now, pro-choicers have had relatively little success in stemming the tide of such laws, except, in limited instances, in the federal court system. As the case of Alabama shows, they haven't even been able to raise sufficient awareness that these invasive laws have been in place for a decade among the same people currently heated up about transvaginal ultrasounds. Some of it may be generational, or cumulative, but all that was before "state-sanctioned rape," and "forced vaginal penetration," which sounds a lot more ominous than "encroachment on First Amendment rights." It helps that we're talking about a movement deeply invested in misogyny that has lately overreached on birth control, used even more widely than abortion. As the University of California at San Francisco's Tracy Weitz put it to the New York Times, “It feels like old-school punishment of women for sexual impropriety, and I think that’s why people are responding so viscerally.” We'll see if it sticks.

Shares