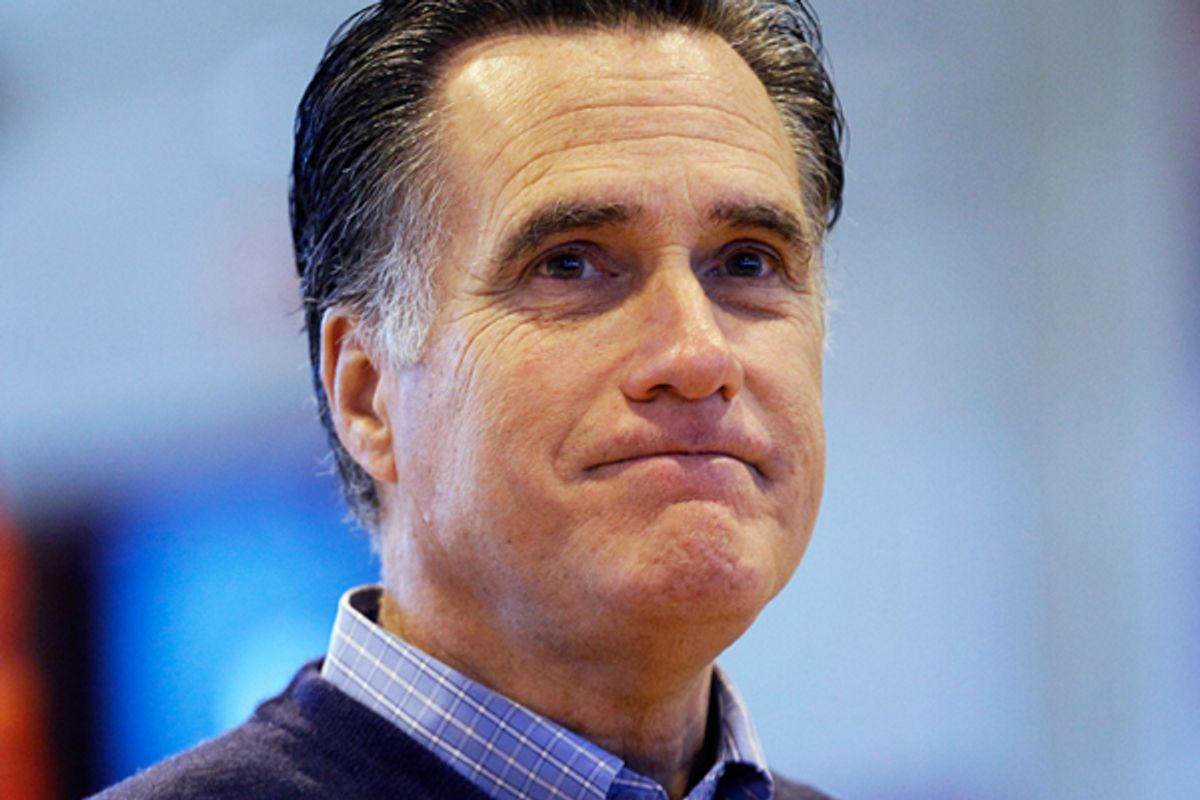

After Mitt Romney's 3-point win in Michigan last night, I argued that he might be a week away from another existential campaign crisis. I'd like to take that one back: The next crisis could kick off this Saturday. That's when Washington state Republicans will hold their caucuses, and the signs are already ominous for Romney.

In general, caucus environments, with their small, activist/ideologue-oriented voter pools, are problematic for Romney, whose biggest obstacle is suspicion from the party base. And cultural conservatives have made waves in Washington before; in 1988, when the religious right was still in its infancy, Pat Robertson crushed Bob Dole and George H.W. Bush in the caucuses -- the only defeat Bush suffered on Super Tuesday that year. So it's probably not surprising that the only recent poll in Washington, conducted by PPP and released a week ago, gives Rick Santorum a 38 to 27 percent lead over Romney.

Thus, it seems likely that Romney will follow-up his big, must-win triumph in Michigan with a loss (very possibly a lopsided one) that will remind the political world all over again how much the base of the Republican Party would rather someone else win the nomination. The news of another humbling setback for the front-runner could stall whatever momentum Romney carries into this weekend, and the timing would be made worse by what's on tap for next week: Super Tuesday.

The playing field next Tuesday is tricky for Romney. He'll win his home state of Massachusetts, Virginia (where his only opponent on the ballot is Ron Paul), Vermont and probably Idaho (based on the state's large Mormon) population. But he could easily lose Ohio, where a poll this week put Santorum up by 11 and where he'll face all of the challenges he faced in Michigan without any native state advantage. And he has to contend with serious ideological/cultural hurdles in Georgia, Tennessee and Oklahoma, where evangelical Christians -- most of them Pentecostals and Southern Baptists, who tend to be particularly suspicious of Mormonism -- will comprise overwhelming majorities of the GOP primary electorate. There's also the caucus states of North Dakota and Alaska (another Robertson '88 win), which pose the same problem for Romney that Washington does this weekend.

It's a given that Romney will lose some contests next week, but the question is whether he'll be able to make surprising inroads -- maybe winning Ohio and a (non-Virginia) Southern state, or at least coming close somewhere in Dixie -- or if his success will be confined to his four safe states, with ugly results everywhere else. Sean Trende of RealClearPolitics estimates that Romney will win the most delegates next week and emerge from the day about 130 ahead of Santorum, but still nowhere near the magic number needed for a first ballot nomination. In other words, the political conversation could be right back where it was in the run-up to Florida and in the run-up to Michigan, with Romney reeling from a painful setback and badly in need of a meaningful victory to quell the panic and alarmism.

The history of this campaign suggests Romney is almost destined to win when he absolutely must and that he probably is on his way to the nomination -- if only because of the failure of any of his opponents to parlay their various moments in the spotlight into a permanent coalition of the GOP base and the party's opinion-shaping class. But the road to a delegate majority is looking like it will be longer and more humbling for him than for any other modern nominee of either party.

Just consider the cases of Bill Clinton in 1992 and Michael Dukakis in 1988, the two previous major party nominees who faced crises most similar to the one Romney just endured in Michigan. Clinton was forced into a must-win contest in New York after a shocking loss to Jerry Brown in Connecticut, while Dukakis' lopsided loss to Jesse Jackson in Michigan also made New York a must-win venue for him. But both Clinton and Dukakis had little trouble rallying the party and fending off their rivals; they both broke away and won their must-win tests by comfortable double-digit margins, and never looked back. Each race essentially ended on the spot.

But that doesn't look like it will be Romney's story. Actually, it already isn't Romney's story. Under the Dukakis/Clinton model, the GOP race should have been settled in Florida, when Romney first faced a do-or-die test; there should have been no second coming for Santorum after that, and Michigan shouldn't have been a 3-point nail-biter for Romney. The party should have rallied around Romney and his remaining opponents should have finished as afterthoughts in the remaining contests. Instead, Santorum posted a three-state sweep of Colorado, Missouri and Minnesota and nearly caught Romney in Michigan.

Again, it's still fair to call Romney the clear favorite to win the GOP nomination, and the convention deadlock scenario remains a remote possibility. But it looks like Romney will continue taking primary season hits for weeks, maybe even months, to come. Even by the standards of previous nominees who were severely roughed up by the primary process, this has been -- and still is -- a uniquely rough ride for Romney.

Shares