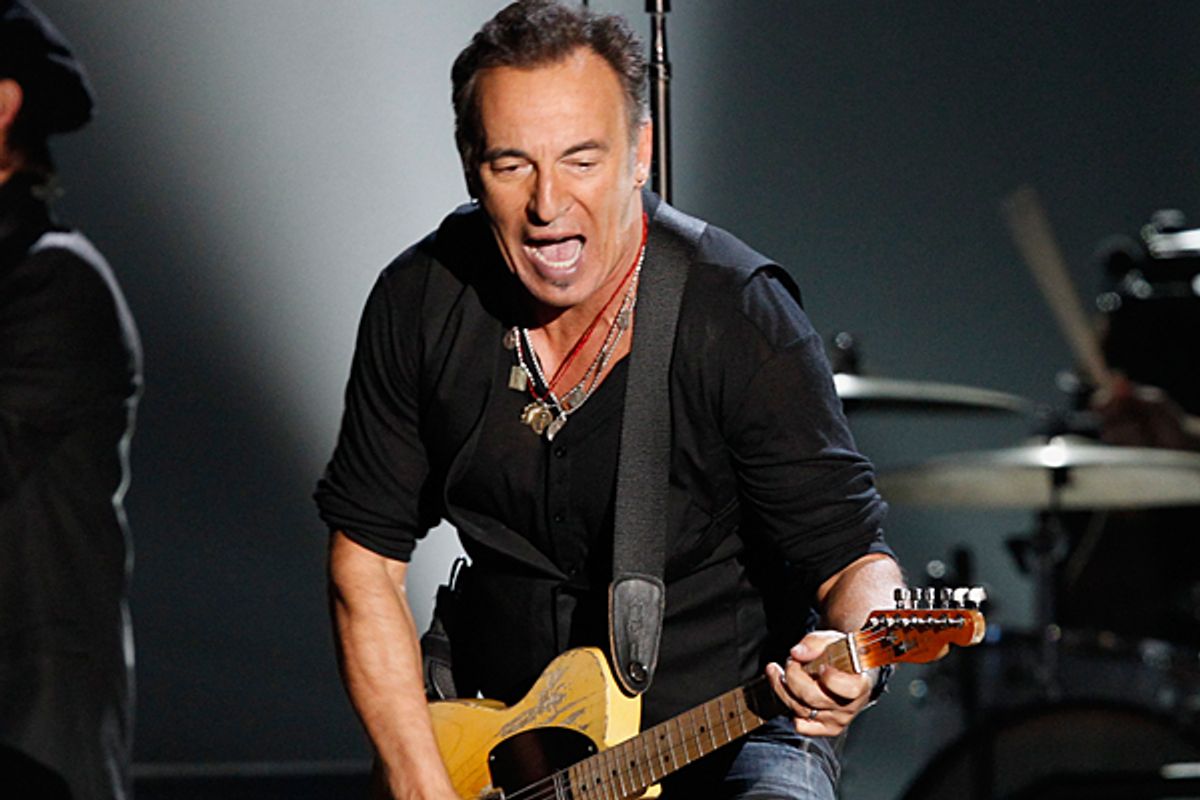

Bruce Springsteen is 62, a little old for a pop star but a good age for a presidential candidate. He was born in the late 1940s, a child of the very first years of the baby boom, as were both Mitt Romney (who is two years older than him) and Rick Perry (who is one year younger). A number of times over the years, semi-sincere New Jersey fans have threatened to draft Springsteen as a candidate for the U. S. Senate, but the singer has wisely demurred. Nevertheless, he is widely viewed as one of the most politically active U.S. pop stars of his generation, and an especially vivid presence during presidential election years.

It is hard to remember it now, but in the beginning of his career Springsteen was largely apolitical. During his first decade and a half as a professional musician, he made almost no political endorsements or even statements from the stage. In November of 1980, he told an audience at Arizona State University that the election of Ronald Reagan “frightened” him, but he didn’t specify just what he was afraid of. In September of 1984, Reagan’s reelection team, looking for local references to liven up a campaign stop in Hammonton, N.J., had Reagan name-check Springsteen in that day’s variation on the president’s standard stump speech. When informed of this, Springsteen tried to shrug off the association and distance himself from Reagan, but there were certain vague similarities. More than anything, Springsteen and Reagan both often saw life in the United States as the same essential conflict: a war between individuals with dreams and the larger institutions that sought to keep them down.

Being a pop star doesn’t have much in common with being a president, but it does have a great deal in common with being a presidential candidate. Both pop stars and presidential candidates can’t just sell their material. To be widely popular, they have to sell a vision that unifies that material. To tell the truth, in 1984 Springsteen and Reagan did have strikingly similar ideologies, even if they were politically far apart -- and that was Springsteen’s dilemma. Even if it is necessary for pop stars to sell a national vision, policy and government have nothing to do with their jobs. Nevertheless, if Springsteen didn’t want his audience to get too comfortable with his ideological similarities to Reagan, he had to find some way to make their political differences more explicit.

From the fall of 1984 on, activism — particularly attention to local causes — became a regular part of Springsteen’s concerts. His public attachment to World Hunger Year, City Harvest and Amnesty International, among other broad-based organizations, became well-known, but he also made sure to invite local causes to set up booths at each of his venues. He began, not only to take much more open stands on the issues about which he cared, but to inform himself in more detail about those issues so that he could speak more knowledgeably to them.

In 1996, he performed at rallies to defeat California’s anti-affirmative action Proposition 209. In 2004, he endorsed a presidential candidate for the first time, John Kerry, and headlined one of the pods of the Vote for Change tour, which sought to build awareness and support for Kerry’s candidacy in swing states. Four years later, Springsteen was an earlier and even more enthusiastic supporter of Barack Obama. As he told a crowd at a voter registration rally in Philadelphia in October of 2008, “I’ve spent most of my creative life measuring the distance between [America’s promise and its reality] ... I believe Sen. Obama has taken the measure of that distance in his own life and in his work, and I think he understands in his heart the cost of that distance, in blood and in suffering, in the lives of everyday Americans.“

Like many Americans, Springsteen has apparently spent time over the last four years measuring the distance between the promise of Mr. Obama’s candidacy and the reality of his presidency. At a press conference in Paris last month to promote the release of his new album "Wrecking Ball," which will be in stores March 6, Springsteen gave a mixed to favorable review of President Obama’s first term, commending the president’s hard work on healthcare and his reduction of the war in Afghanistan but expressing frustration that neither effort went further. At the same press conference, Springsteen was more unalloyed in his praise of Occupy Wall Street, for their introduction of the very idea of income disparity to the national dialogue. Significantly, he told reporters that he probably wouldn’t take part in the presidential campaign this year, suggesting that it had been more essential to get up off the bench in 2004 and 2008.

As much as Springsteen may applaud Occupy Wall Street, much of "Wrecking Ball" predates it. At least two of its songs (“Wrecking Ball” and “We Take Care of Our Own”) were written in 2009, in the first shock of the current recession, and another (“Land of Hope and Dreams”) dates back 13 years to the days of Starr vs. Clinton. Here, as in his last several albums, Springsteen references the botched handling of Hurricane Katrina on multiple occasions, with at least two songs specifically calling back to that moment and others seemingly alluding to it. While some of the songs on "Wrecking Ball" do address income inequity, a far more abiding theme on the album is unemployment, specifically among those who do manual labor. The woeful narrator of “Jack of All Trades” spends six minutes listing all the jobs he would be willing to do, just to put bread on his family’s table, and not one of them is a desk job. The narrator of “Shackled and Drawn,” one of the album’s best songs, is far more assertive and direct. “Let a man work — is that so wrong?” he righteously yells. “Freedom, son,” he declares, “is a dirty shirt.”

Springsteen may be a lifelong individualist, he may be every bit as suspicious of institutions and bureaucracies as Ronald Reagan was, but he clearly doesn’t believe that success is wholly individual either. There isn’t a Social Darwinist bone in his body, and Ayn Rand may very well be his ideological antipode. In paying tribute to OWS at the Paris press conference, it was this sort of solipsistic individualism against which Springsteen most directly raged, accusing those who disproportionately profited from the boom years of “a complete disregard for the American sense of history and community.”

The history and community to which Springsteen most clearly appeals on "Wrecking Ball" and throughout his career is the workingman’s world of his youth, a world of factories and union halls, in which good-paying jobs, benefits and affordable housing were much more widely available to those who might not have an Ivy League education but were willing to get their shirts dirty. For decades now, since 1978’s "Darkness on the Edge of Town" at the very latest, Springsteen has been lamenting the loss of that world, as globalization has seen the union-made jobs of Springsteen’s childhood vanish or flee overseas. In “My Hometown,” the closing song on 1984’s "Born in the USA," Springsteen lamented the loss of a local textile mill, famously declaring that “these jobs are going, boys/And they ain’t coming back.” On "Wrecking Ball," in the deliberately titled “Death to My Hometown,” the castoff workers aren’t just lamenting, they’re pitchfork-and-torches mad. Even the seemingly more resigned narrator of “Jack of All Trades” is looking for a gun in that song’s last verse, to use on those responsible for his underemployment, if he can even find them.

Springsteen knows, more than anyone perhaps, that neither this cause nor these characters are new. "Wrecking Ball’s" final song, “We Are Alive,” specifically links the struggles of 19th-century railroad strikers and 20th-century civil rights activists to 21st-century immigrants who die during border crossings. These are the citizens of Bruce Springsteen’s America, generation upon generation who have looked to their more affluent neighbors for a fair shake and not a handout. The music in which Springsteen sings of these characters is old, too. In fact, it is doubly old: The songs and their arrangements stem from Springsteen’s love of early 20th century folk, blues and gospel; and in Ron Aniello’s production, those songs and arrangements are frequently infused with audio samples drawn from the Smithsonian’s archive of Alan Lomax’s 1930s and 1940s field recordings. The sounds on "Wrecking Ball" (as on Jay-Z and Kanye West’s recent "Watch the Throne") aren’t new, but the artists have tried to make them fresh for our ears, because we need to listen to them again. Indeed, the ideas on "Wrecking Ball" (as on Ani DiFranco’s recent "Which Side Are You On?") aren’t all that new either, but we need to give them a fresh hearing too, because it is blind faith in progress that got us into this mess in the first place.

For a young woman or man around the age of thirty today, the world of Bruce Springsteen’s childhood is unimaginable. A federal government that funds college and cheap mortgages? Employers that routinely supply health benefits and pensions? To those unfamiliar with American history, that doesn’t sound like the world of the Greatest Generation; it sounds like a socialist fantasy. Obviously, the world has changed immensely during the last 62 years; neither America’s economy nor the world’s generates jobs and wealth in quite the same way as they did in 1949. But justice does demand that the “right to work” mean something more than the right for employers to underpay their employees — and it’s not Bruce Springsteen’s job to determine the details of how to make that happen. He’s measured the distance between our past and our present, between our promises and our reality, and he’s given us the benefit of his vision. It’s up to presidents and senators to make that distance shorter, to turn visions into policy and actually govern.

Shares