Among the most insulting memes in the national debate about government are those about leadership -- in particular, the three-pronged notion that assumes that 1) running a public institution requires no public-sector experience at all, 2) public sector experience is something inherently bad, and 3) a public institution will actually benefit from an infiltration of business executives, because those bare-knuckled suits will "run government like a business."

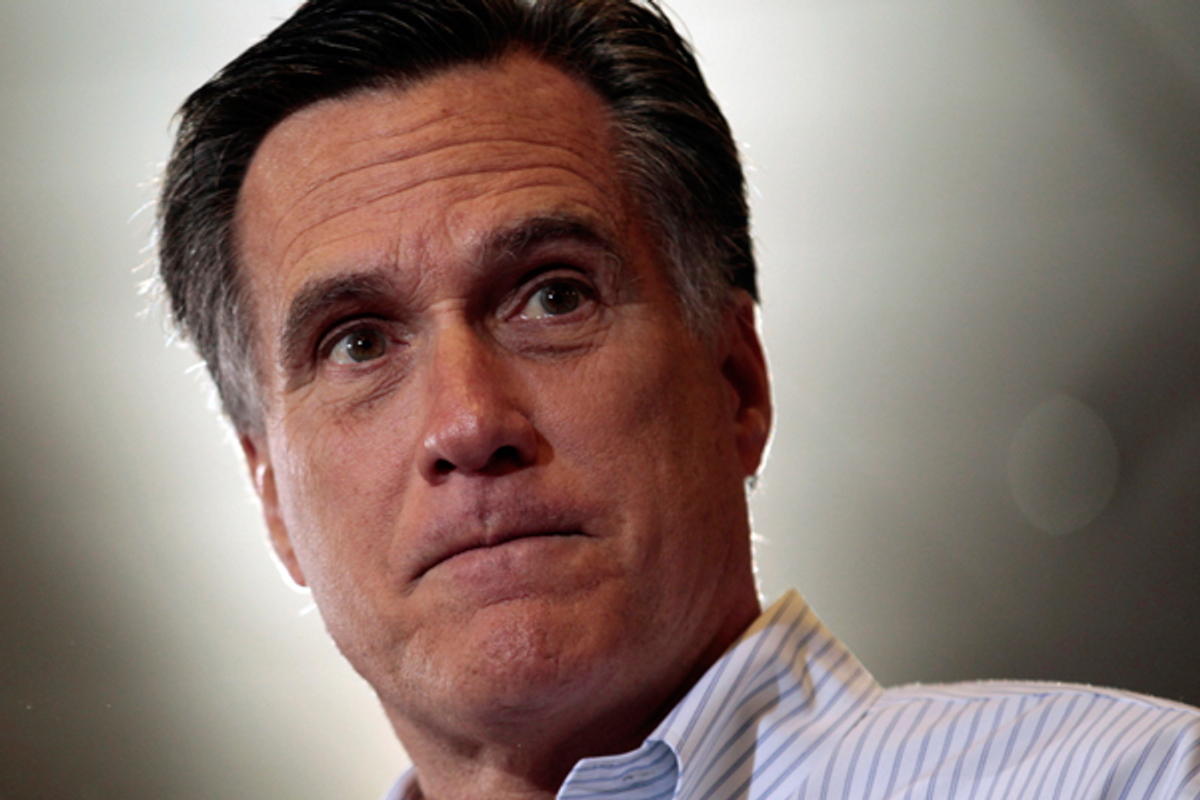

Bizarre as it sounds in the post-financial-meltdown era -- how can anyone want a Wall Street executive running anything? -- the idea persists, and with few real challenges to its fundamental premises. Indeed, the leading candidate for the Republican nomination, Mitt Romney, is a guy with just four years of experience in government (far less than even President Barack Obama had when he ran for president) -- a guy whose entire candidacy is predicated on the notion that only the ruthlessness and know-how of a private equity barbarian can get the government to start doing what needs to be done.

The unasked question, of course, is whether there is any truth to those assumptions. That question raises other uncomfortable ones, such as: What actually happens when corporate executives with zero relevant experience run public institutions? And what do those institutions do when said executives run them "like private businesses"?

While there's no single answer for every case, three archetypal stories from my home state of Colorado underscore the typical -- and predictable -- results.

This is a state whose political culture so loathes the notion of public service and so deifies the Heroic Corporate Executive that a virtual unknown -- Bush family member Walker Stapleton -- was recently elected to the State Treasurer's office on the basis of a television ad campaign that featured the candidate bragging: "I haven’t spent a day of my career inside of government and my opponent hasn’t spent a day of her career outside of government.” Not surprisingly, Stapleton has brought corporate greed-is-good narcissism and ethics-free mentality into state government, making early headlines with a precedent-setting plan to simultaneously run the Treasurer's office -- which oversees public investments -- and keep his job as a private real estate investment executive. In other words, Stapleton has shown that bringing the cutthroat, profit-focused mission of business into government often means forcing the public to accept potentially huge conflicts of interests that could cost taxpayers dearly.

Likewise, the Denver Public School system will be struggling for years to clean up the financial disaster wrought by two corporate executives, Michael Bennet and Thomas Boasberg, who were granted school leadership positions despite having no experience running education institutions.

Bennet became superintendent in 2005, after previously serving as a Clinton administration lawyer, a corporate raider for right-wing billionaire Philip Anschutz and a political aide to Denver's mayor. Boasberg, a telecom lawyer and Bennet's lifelong friend from their days at St. Albans in Washington, was appointed deputy superintendent. Within a few years, the pair had brought Corporate America's fast-and-loose accounting tricks into the schools, cutting a pension refinancing deal with major Wall Street banks -- one that used complex interest-rate swaps to enrich those banks, while putting the school system's long-term finances in serious jeopardy.

Then there is Colorado's public university system, now run by oilman and former Republican Party Chairman Bruce Benson. Having no experience running a public higher education system, Benson's tenure has been marked by callous "let them eat cake" declarations and financial scandals.

These last few months have been illustrative. With U.S. News and World Report noting the comparatively high cost of attending the University of Colorado, and with pressure building to make CU more affordable, Benson callously declared, "I've never heard a complaint from parents that tuition at CU is too high." Then, like a CEO quietly juking an earnings report to hide big giveaways to executives, Benson tried to ram through a massive 15 percent tuition increase as quickly as possible, explicitly to avoid media attention -- all after using the previous year's tuition hike to finance huge bonuses to already-wealthy CU administrators.

Of course, recounting this trio of cautionary tales is not to argue that prior public-sector experience is always a prerequisite for effective stewardship of public institutions. But it is to suggest that the dominant "run government like a business" sloganeering obscures an important truth: namely, that public administration is a professional expertise unto itself -- one whose nonprofit mission, obligation to taxpayers, and responsibilities to the common good are fundamentally different from the private sector's objectives.

This is why putting public power in the hands of those who have no experience using it always brings a risk -- and, as these events prove, those risks are much greater than the standard concerns that corporate human resources departments fret over when hiring an employee with no relevant experience. And yet, from electing governors with no public-sector experience to voting the Tea Party's businessmen-turned-politicians into Congress, the zeal to corporatize the government is somehow intensifying. Even at the most local level, we see its pernicious effects. As Joanne Barkan previously reported in Dissent magazine, corporate-financed foundations are now working to replace experienced public servants with employees who have no relevant experience whatsoever:

The mission of both is to move professionals from their current careers in business, the military, law, government, and so on into jobs as superintendents and upper-level managers of urban public school districts. In their new jobs, they can implement the foundation’s agenda...

According to the Web site, “graduates of the program currently work as superintendents or school district executives in 53 cities across 28 states. In 2009, 43 percent of all large urban superintendent openings were filled by Broad Academy graduates.”

The second project, the Broad Residency, places professionals with master’s degrees and several years of work experience into full-time managerial jobs in school districts, charter school management organizations, and federal and state education departments...It’s another success story for Broad, which has placed more than two hundred residents in more than fifty education institutions.

After the collapse of Enron, the accounting industry scandals, the disastrous effects of Halliburton CEO Dick Cheney's vice presidency, and the Wall Street implosion, you'd think we'd be moving in the other direction -- you'd think we'd be more wary about putting businesspeople in government, and more focused on valuing those with public sector experience. But, instead, the era of polarized politics has created a bizarre psychology in which America now sees the public servant as a Public Enemy, and the corporate executive as the government savior.

Until we recognize the paradox in that thinking, we should expect the same horrifying results from the public sector that we've lately seen in the private sector.

Shares