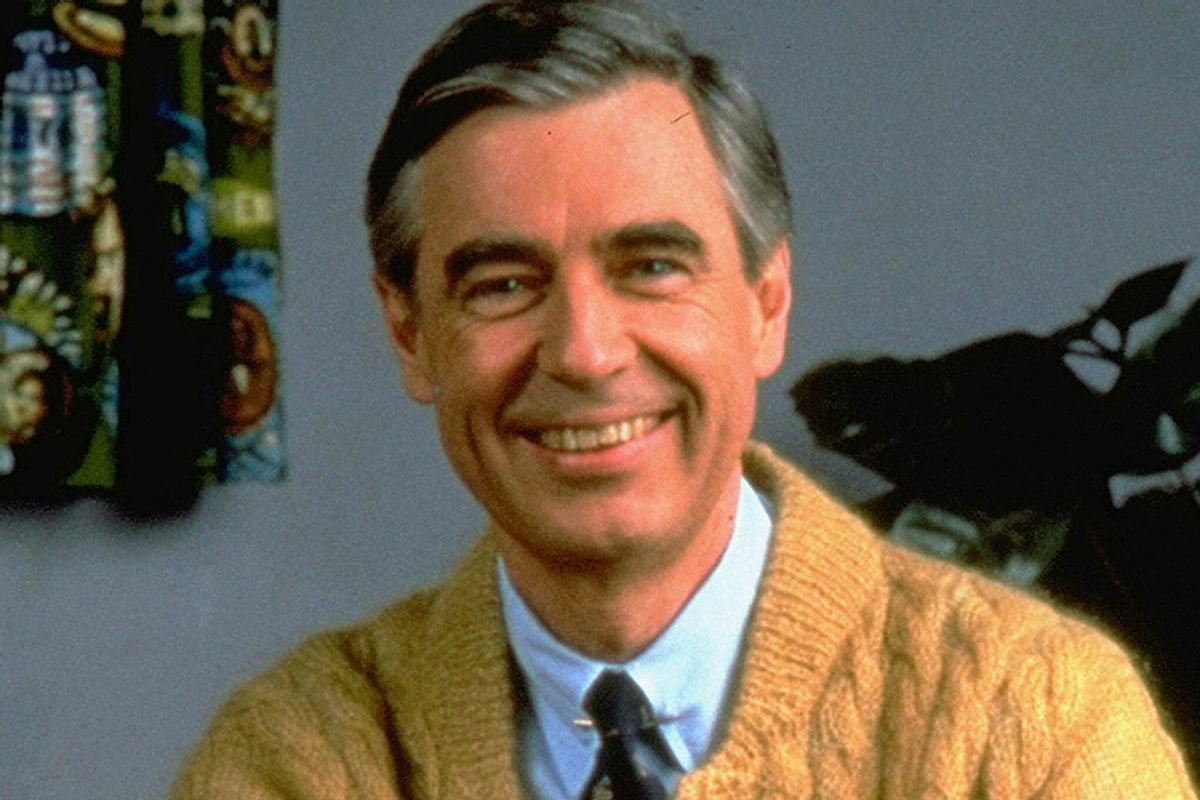

One of the most radical figures of contemporary history never ran a country or led a battle. He was not known for his fiery speeches or his daring action. Instead, he became a legend by wearing a cardigan and taking off his shoes.

Fred Rogers would have turned 84 next week. In honor of his birthday, why not take off your jacket and cozy up to the intimate documentary "Mister Rogers & Me"? Brothers Benjamin and Christofer Wagner's worshipful ode is certainly no match for anything Rogers himself ever created; it's a meandering, not-quite-finished-feeling work that too often veers toward the "me," when Rogers ought to remain front and center. But it does offer the firm reassurance to generations of viewers of how truly fantastic "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" was and why his legacy endures via books and DVDs. And it reminds us how today, nine years after his death, the world needs Mister Rogers more than ever.

Fred Rogers didn't get into television to become famous. He didn't do it in the hope that his sweater would wind up at the Smithsonian -- though it did. Instead, the low-key Pennsylvanian was drawn to the fledgling medium for a far less likely reason -- because he "hated it so." When he turned it on, he later explained, "I saw people throwing pies in each other's faces and I thought, why do we have to show demeaning behavior?" And he set out to create something different. Something that would give children the message his grandfather McFeely always told him, that "There's only one person in this whole world like you" and that "You make each day special, just by being you." He toiled in local television with an early show called "The Children's Corner" and landed on Canadian television for a while until, in 1968, "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" began airing on the still-new Public Broadcasting System.

The show, with its tinkly, Fred Rogers-composed piano music, its gentle puppetry, and its mind-bogglingly leisurely pace, went on to become both legendary and legendarily parodied. Only two edits per minute. No pie throwing. No gimmicks. A mailman named after the host's grandfather.

Yet within that spectacularly deliberate, remarkably plain format, Rogers hit upon something extraordinary. He didn't need any bells or whistles beyond the chimes of the train to Neighborhood of Make-Believe. He gave his audience something different from frantic cartoon animals dropping anvils on each other. He gave them the feeling that they were valued, that they were respected, and that they were safe. He told them, "I'm proud of you," and he advocated against the "bombardment" of their culture. Speaking to filmmaker Wagner years later, Rogers would explain his philosophy, cribbed from author Bo Lozoff, as "Deep and simple is far more essential than shallow and complex."

Simple is hard. Quiet is hard. Both are also, unfortunately, too often mistaken for weak and dumb. The ideals that Mister Rogers tried to instill in the millions of us who watched, rapt, as we shoved our morning Cheerios up our noses today seem nice for the average 3-year-old, but they barely make sense in the complicated, snarky world of adulthood. His ideology seems old-fashioned and a little goofy, a relic of a time in life when one could innocently wake up and still believe in the beauty of one's neighborhood.

But let me tell you – Mister Rogers was fierce. As "Mister Rogers & Me" reminds us, Fred Rogers was the man who, in 1969, went before the Senate to save PBS from sweeping budget cuts. And who, in the briefest, most persuasive speech since Richard III won over Lady Anne, gave the notoriously cantankerous John Pastore "goose bumps" as he quietly described his show and its value to children. When it was over, Pastore shrugged, "Looks like you just earned your $20 million." Want to know what real power looks like? Try hustling for 20 million bucks sometime – and succeeding in fewer than seven minutes -- and see.

Want to see what confidence looks like? When he won his Lifetime Achievement Emmy Award in 1997, Rogers invited the audience to "take 10 seconds to think of the people who have helped you become who you are, those who have cared about you and wanted what was best for you in life." And then, holy crap, he shut that whole show down for 10 seconds while he watched the time. Even Oprah's never been bold enough to devote moments she could spend giving a speech to commanding silence, that sure of the force of saying nothing.

Rogers was a genius of empathy, a man who understood what he called "the drama of childhood." If you watch his shows now, you will remember that they are not just some mellow stroll through fuzzy puppets and happy songs. They tackled the fears and the sadnesses of childhood. They told children how to handle divorce or the death of a pet. He listened to a quadriplegic child talk about his brutal surgeries, and sang to him that "It's You That I Like." And when years later the now grown Jeff Erlanger showed up when Rogers was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame, Rogers bounded out of his seat to leap to the stage not to collect his accolades but to hug his old friend.

Mister Rogers never said that world was an easy place, or that life is all happy songs and feeding the fish. The chubby kid who was bullied by his schoolmates grew to be a man who understood that it was often painful and confusing and lonely. That's precisely why Rogers advised parents, in 1968, on how to discuss the assassination of Robert Kennedy. That's why, when Rogers heard that before 14-year-old Michael Carneal opened fire on his classmates at West Paducah's Heath High School nearly 30 years later, the boy had promised to do something "really big" the next day at school, Rogers said, "Oh, wouldn't the world be a different place if he had said, 'I'm going to do something really little tomorrow?" That's why he dedicated a week of programming to theme of "little and big" ideas, and the joy of thinking small.

Fred Rogers was fearless enough to be kind. Kinder in a single day than many of us can muster up in a week. He wasn't embarrassed to be gentle; he was never too cool to be simply good. He championed "not buying things, but doing things." He created the longest-running program in PBS history, and he didn't do it with mocking or putdowns or smug superiority. He did it by being nice. And nice is incredibly underrated.

Few of us are born with that native humbleness and serenity that made Fred Rogers unique. Few of us could handle his vegetarian, alcohol-free, swimming every day regimen. And hey, some of us think a pie in the face can be pretty hilarious. But you don't have to be a saint or a preschooler to appreciate the rewards of being respectful and compassionate, because none of us ever stop needing compassion or respect ourselves. We can't all be Mister Rogers. But in a world that's often far too cold and mean, one in which bullies can now tyrannize with both a fist or a tweet, we can all stand to be a little bit better neighbors. Consideration and kindness and gratitude aren't make-believe dreams. They're what make us all special. Just by being us.

"Mister Rogers & Me" debuts on iTunes and selected PBS stations March 20.

Shares