"You don't know how many times I've watched that thing," said Caitlin, 10, about the trailer for "The Hunger Games," a movie based on the first of three dark, brutal, bestselling novels by Suzanne Collins. A boy at her school told her she had to read the first book, and after that, "My mom says I started a revolution," passing the books from one classmate to another. Now they're all obsessed. Caitlin's grandmother (a fan as well) made her a replica of the survival-gear-stuffed backpack that the book's heroine, Katniss Everdeen, nabs at the beginning of a life-and-death competition set in a bleak future America. Caitlin and her closest friends talk about "The Hunger Games" several times a day, have nicknamed each other after the characters and are deep in plans to make their own Flip camera video of the book. When the Hollywood version comes out on Friday, they'll be there, celebrating Caitlin's birthday by catching the late-night opening at a San Francisco theater. The only other movie she's even been close to this excited about is "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows."

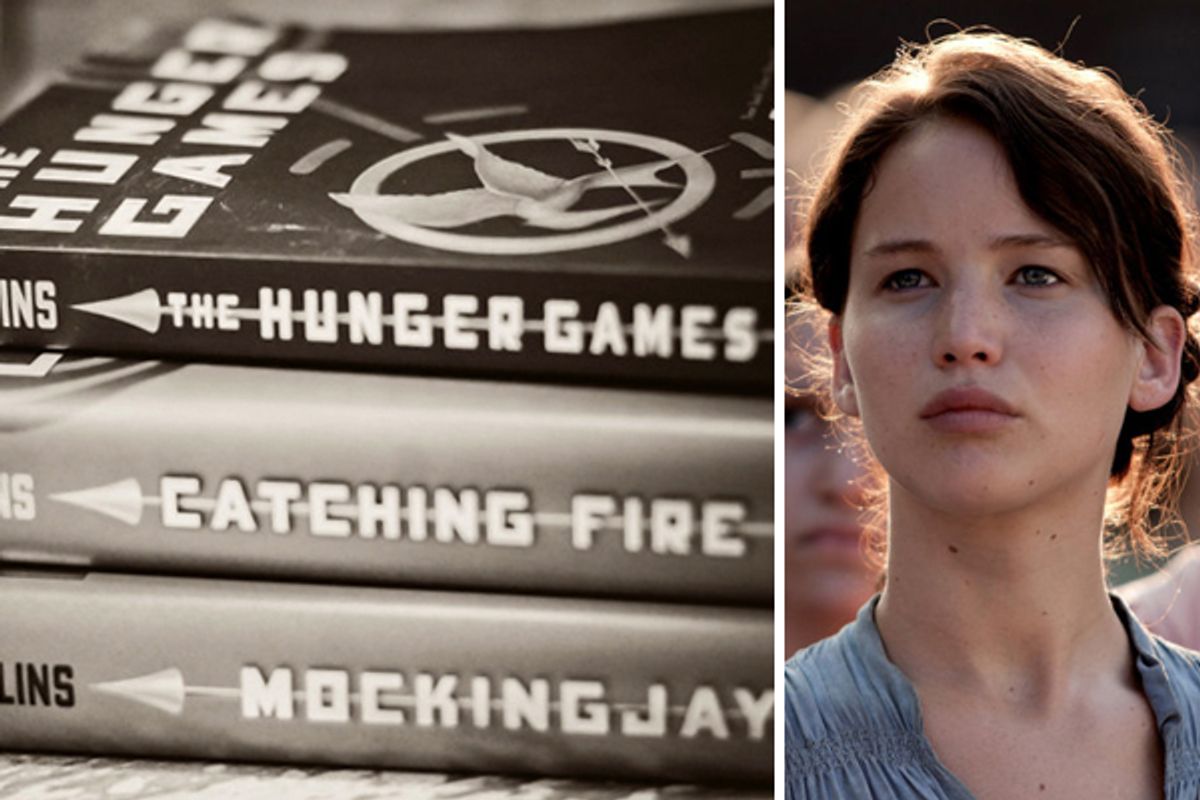

The Hunger Games franchise, with Oscar-nominated actress Jennifer Lawrence in the starring role, aims for a spot in a select but very sweet pantheon: movie adaptations of bestselling children's book series that have become box office juggernauts. The Harry Potter movies set the pattern, and the Twilight films proved that it could be replicated. So far, the Hunger Games' chances look good; according to a poll conducted by MTV's Nextmovie.com, the film version of Collins' dystopian young adult novel is even more eagerly anticipated than "The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn Part 2."

Being made into a movie can do a lot for a book. But consider the boost a book this popular can give to the movie. The Harry Potter and Twilight series delivered up obsessively devoted audiences who speculated about casting for years before the films were released, who debated and pored over every still, poster, teaser, trailer -- in short, every shred of news about the forthcoming cinematic realization of their favorite characters and stories. They loved those books as only kids can, with an intensity that makes for sprawling fan sites and mobbed midnight release parties at your ordinarily sleepy neighborhood bookstore.

The Hunger Games is that kind of series, if for a more serious-minded, science-fiction-loving breed of teen. And then there are the adult fans. The actress Kristen Bell (star of the cult-TV series "Veronica Mars") recently told the Huffington Post that "The Hunger Games" is "all I think about." Bell threw an elaborate Hunger Games-themed party for her 30th birthday: "All my friends dressed as the characters and I dressed as Katniss [Everdeen, the books' heroine]."

As of this writing, the first book in the Hunger Games series has been parked on the USA Today bestseller list for 132 weeks; the second, "Catching Fire," for 131. There are more than 24 million copies of all three books in print. Unlike the Harry Potter series, which was aimed (originally) at middle-grade readers, this is a young-adult epic with a particularly dark premise: In a future version of America called Panem, 12 districts subjugated by a central authority must each send a pair of their children to compete in a gladiatorial contest from which only one will emerge alive. In marked contrast to the swoony vampire romance of the Twilight series, the many harrowing action sequences in "The Hunger Games" make the books equally appealing to boys and girls.

It's indicative of the balkanization of the reading world that if you don't have teenage children, you may not have heard of "The Hunger Games" until quite recently, despite the fact that for several years the book's success has rivaled that of "The Help" and "The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo." Although both Harry Potter and Twilight have demonstrated that there's a sizable adult readership for some children's books, the genre is still (mostly) reviewed in separate publications, shelved in its own section of the library and often sold in separate stores. In fact, children's book publishing operates quite differently from its adult counterpart. And in many respects, that's a good thing.

With the right title, a kid's publisher can deploy something the world of adult publishing can only dream about: a large, well-oiled and highly networked group of professional and semi-professional taste makers who can make that book a hit even before it's published. This is what happened with "The Hunger Games," which landed on the New York Times Bestseller List -- there are separate ones for kids' books -- the week it was released. In the post-Harry Potter and Twilight world, breakout children's series like "The Hunger Games" automatically attract the interest of big-budget Hollywood film producers. That means that the mostly invisible legion of experts who hiked "The Hunger Games" onto the bestseller list will be determining some of the blockbusters you'll see in your local multiplex a couple of years down the road.

Cue the obligatory bad-mouthing of publishing and its antiquated ways. But before you get into that, it's essential to grasp the central, maddening paradox that confronts all book marketers, from venerable New York publishing houses to tiny independent presses: The only thing that reliably sells books is word of mouth, preferably a personal recommendation from a trusted friend. The one successful mass-market book-promoting phenomenon of our time, the Oprah Book Club, was just that -- an endorsement from someone with the very rare gift of convincing millions of people that they know her really well.

Advertising and reviews and flogging on Facebook or Twitter don't help much unless the author already has a large following. A book demands more time and energy from its consumers than a movie or a song, and readers increasingly require a chorus of endorsements before they're willing to try something new. (Think about it: We all have friends who occasionally steer us wrong, but if several of them are raving about the same book, it looks like a much safer bet.) When you can't persuade someone to read your book until somebody else has read and endorsed it, you're in limbo -- like the proverbial job-seeker who can't get hired without experience and can't get experience without a job.

Many of the most arcane practices of the publishing industry are methods for working around this dilemma. It begins even before a book goes to press. Those unfamiliar with publishing's peculiar customs may wonder at the mystique surrounding "in-house enthusiasm," a key factor in the success of any book, whether it's for adults or for children. In an ideal world, publishers would be enthusiastic about every single book they publish, right? But all too often the manuscript doesn't fulfill the promise of the proposal, or the novel that one editor adores leaves everyone else cold. The ability of a book to generate interest in random staff members is a publisher's first sign that it has legs. This is the beginning of the long and elaborate winnowing process that separates the also-rans from the hits, much of which happens even before store clerks take the books out of the carton.

"The Hunger Games" started out with an advantage. Scholastic Books, Collins' publisher, had done well with Collins' previous series, the Underland Chronicles, five books for middle-grade (8-to-12-year-old) readers about a boy who discovers a gritty fantasy world under the streets of New York. With that in mind, Scholastic bought "The Hunger Games" on the strength of a four-page proposal covering all three books of the projected YA (young adult) trilogy. In the summer of 2007, Collins submitted a draft of the first book to three editors, including Scholastic's executive editorial director, David Levithan, and Kate Egan, a freelancer who has worked on all of Collins' books.

Levithan and Egan were among the first readers to be sucked into the irresistible tractor-beam of Collins' narrative. The book begins with the 74th annual Hunger Games lottery in the hardscrabble mining region of District 12. The heroine, 16-year-old Katniss Everdeen, is skilled with bow and arrow; her family survives on her poaching. In the lottery, Katniss' beloved little sister is selected as a tribute (a death sentence for someone so young), and Katniss volunteers to go to the games in her stead. She's whisked away to the decadent Capitol, where she undergoes training -- and a rather fabulous makeover -- alongside her fellow District 12 tribute, Peeta, the baker's son. All of this builds up to the Games themselves, conducted in a fenced-off wilderness preserve in which the tributes battle for food, supplies and weapons while invisible cameras broadcast their every move.

"The Hunger Games" is a novel that takes to heart Billy Wilder's famous dictum for screenwriters: "Grab 'em by the throat and never let 'em go." Before she turned to books, Collins, who has a background in theater, wrote children's television shows for Nickelodeon. "I think that writing for episodic television, knowing that you have to have that rising and falling tension, and end that episode at a particular place, has served her very well," said her agent, Rosemary Stimola. Karen Springen, a former Newsweek reporter and one of the first journalists to extoll "The Hunger Games," puts it this way: "She knew how to do cliffhangers to get you to come back after the commercial break. Each chapter is a cliffhanger, and each book is a cliffhanger."

Scholastic employees began eagerly passing the manuscript around the office. It was the first stirring of what would become a tidal wave of word of mouth. "When you have the kind of book," said Rachel Coun, executive director of marketing, "where assistants from other departments, even though it's not their job, come asking for the galleys because they've heard it's really great, you know you have something." "We made a lot of copies," said Levithan. "Coming out of the fall sales conference, everyone knew that the best way to generate excitement about 'The Hunger Games' was to get people to read 'The Hunger Games.'" That isn't as easy as it sounds; over 20,000 new children's books are published annually, and the people Scholastic needed to reach -- people outside the company -- are drowning in the piles of books arriving from hopeful publishers.

In January, the book's marketing team decided to send out photocopies of the manuscript instead of the nicely bound proofs that are typically submitted to industry professionals before the finished version of a book comes off the presses. "We didn't want to wait until we had advance readers copies," said Levithan. "We wanted key booksellers and key librarians to read it as soon as possible." Just as significant as the timing, a choice like this is part of an informal semaphore system between publishers and the all-important first readers of any new children's book. A Xeroxed, plastic-comb-bound manuscript conveys both urgency and the conviction that here's a title that doesn't need attractive packaging to make an impression. "It signals that this is something they think is special," said Andrew Medlar, youth materials specialist for the Chicago Public Library. "It's not something we do very often," Levithan concurred.

Scholastic sales reps were given a limited number of manuscripts to distribute to their list of "Big Mouths," children's publishing lingo for booksellers who have exceptional influence with co-workers and peers. These people run regional associations, organize book fairs and set up school events. Teachers and librarians come to them for hot tips on new kids' titles.

Carol Chittenden, a classic Big Mouth, is a co-owner of Eight Cousins bookstore in Falmouth, Mass. and founded the New England Children's Booksellers Advisory Council, which (among other things) maintains a website where members can swap opinions on forthcoming titles. Her cozy children's bookstore in a small Cape Cod town may seem a long way from Hollywood, but people like Chittenden -- who's been selling kids' books for 22 years and who instantly recognized "The Hunger Games" as "major" -- are the wellsprings of word of mouth, a sort of viral ground zero where phenomena like Hunger Games fandom are born. These people are, after all, the ones who made Harry Potter a household name.

We now come to a precarious crossroads in the fate of any book, that moment when it passes out of the hands of the publisher, who has a vested interest in its success, and under the scrutiny of much tougher judges. Getting Big Mouths like Medlar and Chittenden to read the book in the first place is half the battle. Sales representatives like Nikki Mutch, who gave Chittenden her copy of the manuscript for "The Hunger Games," are a key conduit between publisher and bookseller, the crucial node where, if all goes well, in-house enthusiasm translates into real-world buzz. The title "sales rep," with its Willy-Lomanesque connotations of briefcase-toting drudgery, doesn't convey the persuasive mojo these men and women can wield; their credibility, if they use it wisely, can be immense. "We totally trust her," said Heather Hebert, manager of Children's Book World, in Haverford, Pa., of her Scholastic sales rep. "She definitely was the reason why we all read ["The Hunger Games"] immediately. When she says it's good, it's good."

If the excitement back in headquarters manages to get transmitted to the publisher's sales reps in the field, and the reps in turn transmit it to booksellers, and if the marketing department persuades major children's librarians to give the book a tumble, then it's off to a good start. But a book can still stall out if that first line of expert readers isn't impressed. "The Hunger Games," however, proceeded to wow the Big Mouths. Rachel Coun and Scholastic's head of publicity, Tracy van Straaten, began compiling testimonials from booksellers and librarians, many of whom mock-complained of being kept up all night, compulsively reading the manuscript; then they incorporated the quotes into their marketing campaign, reminding the wider network that leaders in their field were loving the book.

That spring, a full six months before "The Hunger Games" was set to publish, the official advance reader's copies were among some of the most sought-after items at the conferences and conventions where publishers present their titles to booksellers and librarians. In early summer, Publishers Weekly, the industry's trade publication, ran a story on how Scholastic had twice doubled the book's print run in response to "early raves, particularly online, where commentary has lit up blogs and listservs." The book was well on its way to bestseller status even before the cover art -- a major conundrum for Scholastic -- had been finalized.

To anyone accustomed to the often haphazard methods of adult book marketing, the apparatus marshaled on behalf of kids' books before and after publication is both awe-inspiring and enviable. This is old-school social networking -- conferences, presentations, in-store events, face-to-face recommendations to customers and colleagues (referred to as "hand selling" in the book trade) -- rendered even more powerful by new technology. Every children's bookseller and librarian I contacted for this article belongs to at least one listserv where they constantly evaluate new books with their peers. Months before "The Hunger Games" was published, Kathleen Horning, who works at the Cooperative Children’s Book Center in Madison, Wis., a resource center for librarians, created a forum for the book on GoodReads, a social networking site for book lovers with over 6 million members, so she could chat about it with anyone who'd also gotten their hands on an advance reader's copy. It was up and thriving by the time the book was published

Most booksellers and librarians want to foster reading, but none are more evangelical than the ones who specialize in kids' books. Adult books may boast the more prominent bestseller lists and reviews, but there are entire industries and professions -- with outposts in every town in America -- that have made it their mission to get children to read more books. There are no institutions with the equivalent reach and dedication when it comes to promoting adult reading.

A school librarian like Alli Decker, head librarian at St. Mark's School in San Rafael,Calif., may not have Oprah's reach, but she's got a lot more depth when it comes to putting a book in the hands of one of her students. "In the best-case scenario," she explained, "I know them from first grade, when they start to read independently, on up. I know who I can challenge and who I can't. I know who is willing to try something new and who isn't." "That's what [children's] librarians basically want to do," said Horning: "find books that kids really, really want to read."

To that end, librarians have perfected the art of the "booktalk," a term that, in recent years, has morphed into a transitive verb: Horning describes "The Hunger Games" as "a really fun book to booktalk." A booktalk is a pitch, several minutes long, delivered to fellow librarians, teachers, parents and young library patrons. Librarians are invited to speak at schools and bookstores, or they travel to branches to help fill in the gaps for overworked local librarians. They are, in effect, unofficial traveling salespersons for the books they love, supported by the apparatus of respected, publicly funded institutions. Parents and teachers who are too busy to keep up with new children's books themselves treat their advice as gospel. Andrew Medlar of the Chicago Public Library not only orders books for 79 branches and booktalks his favorite titles to his staff, he compiles lists of recommendations that are posted to the library's website and distributed in schools, bookstores and libraries. He also nominates for important prizes.

Its high-concept premise made "The Hunger Games" an ideal candidate for booktalks. "It's one of the easiest books to interest a child in reading," Horning explained. Of course, librarians and teachers don't always love the same books that kids do. Over the years, they've tried to steer their patrons away from what has been viewed as low-quality, if popular, series fiction: the Hardy Boys detective stories, the horror series Goosebumps, and glitzy tales of teenage hedonism like the Gossip Girls books.

"The Hunger Games," by contrast, hits what Chittenden calls "the sweet spot of the market." The romantic triangle of Katniss, Peeta and Gale (the boy Katniss left behind in District 12), combined with the combat and adventure of the Games themselves, appeals to a wide spectrum of teen and tween readers. Parents, teachers and librarians seize on the social and political commentary in the novel's depiction of an authoritarian government, an exploited underclass and reality-TV voyeurism pushed to grotesque extremes.

"There were so many ways that high school teachers could use this in their curriculum that we felt that it was important for them to know about it," said Heather Hebert of Children's Book World in Haverford, Pa. A classroom assignment will result in multiple sales, which is why many booksellers make a point of sharing advance reader's copies of promising books with local educators. "We'll get a few extra ARCs and give them to the teachers," says Becky Anderson of Anderson's Bookshop, which has two stores in Illinois. "They'll start reading that book out loud in class to the kids, just to tease them with the first few chapters." Then, "we send out a pre-sale form so all the kids can buy it." It's a strategy that's worked like a charm for many a drug dealer.

One high school teacher Anderson works with likes to enlist the whole school in staging elaborate book-inspired events. Within weeks of the publication of "The Hunger Games," Collins made a personal appearance at the school. She was honored with a veritable pageant. Students marched before the author costumed as the district tributes, the language arts class made posters with quotes from the novel (to illustrate such rhetorical devices as irony) and the art class re-created one of the settings in the Arena. Even the business class participated by budgeting, raising money for and finally commissioning a pendant of Katniss' emblem, a bird called a mockingjay, to present to Collins at the event.

It's hard to imagine the first book in any adult series being greeted with a comparable level of grass-roots hoopla: buzzed, booktalked and big-mouthed for months before it appeared on any bookstore display table. When "The Hunger Games" finally reached its intended audience, 12-to-18-year-olds, it proved to be as big a hit as Chittenden and her colleagues had predicted. Kids, it turned out, loved it just as much as all those adults who have made it their life's work to discover the books kids will love. (Go figure.) From that point, it only got hotter: There is no more fertile petri dish in which to grow world of mouth than a high school. When "Catching Fire" was published the following year, it instantly shot to the No. 1 spot on the USA Today bestseller list.

"The Hunger Games" also arrived at a moment when many adult readers had turned to YA fiction for their own recreational reading. Several booksellers cite a boom in YA blogs as contributing to spreading the word about the series. "The [bloggers] we know," said Hebert, "who come to our store all the time and to our events, they seem to be women in their mid-20s. They're not teens, but they don't have families yet, most of them." These bloggers network with each other constantly via Twitter and Facebook, and when the "Hunger Games" sequels came out, they were often first in line for the midnight release parties. "They're great, because they get just as excited as we do," said Hebert. "And they can actually come at midnight. A lot of our customers are too young to stay up that late."

Scholastic didn't just sit back and watch all this transpire. They buttonholed booksellers and librarians at conferences with books in hand, insisting that everyone they knew had to read this advance reader's copy as soon as possible. They distributed banner ads, countdown clocks and a grainily ominous book trailer. They went through countless iterations of the cover before settling on an iconic mockingjay emblem as an appropriately unisex image for the franchise. But as the American publishers of the ultimate word-of-mouth phenomenon, Harry Potter, they also bow to the power of what van Straaten calls "kismet." With "The Hunger Games," "We got it in the hands of the right people. That's what publishers do," she said. "You're leveraging one thing to build the next thing. You need the enthusiasm internally to convince that first layer of gatekeepers. Once you have the kudos of those people, you can get these people, and so on." "The viral world changes monthly," said Scholastic's Coun, "so our marketing has to change along with it. Still, the traditional thing -- you read the book and it's a great book -- is what's going to sell it the most."

By now you've probably noticed that two prominent elements of the book-publishing landscape -- Amazon and ebooks -- have yet to crop up in this story. While Amazon was as enthusiastic as other booksellers about the publication of "The Hunger Games" (and Collins is a member of the elect Kindle Million Club -- a half-dozen authors who have sold more than a million titles in the Kindle format), the e-tailer just doesn't have the community presence of a bricks-and-mortar children's bookstore.

High school teachers aren't checking in with Jeff Bezos to find out what to assign to their classes next fall. Desperate parents don't ask him for a title that will get their 14-year-old son reading again. Furthermore, teenagers and younger children still list browsing in bookstores and libraries as the primary ways they find out about new books and authors. They've been much slower to adopt e-books than older readers. Some observers think this is because e-reader devices are too pricey for kids; others say that kids see print books as a pleasant break from staring at screens all day. YA titles are selling well in various e-book platforms, but no one knows how many of these books are being bought by the growing adult readership for YA.

The possibility of "The Hunger Games" crossing over to adult readers (the Holy Grail for children's book marketers) got its first big public boost when Stephen King reviewed it for Entertainment Weekly (even if he only gave it a B) a few days after the book came out. Not long after that, Stephenie Meyer, whose "Twilight" also made significant inroads with adult readers, raved about "The Hunger Games" on her blog: "I was so obsessed with this book I had to take it with me out to dinner and hide it under the edge of the table so I wouldn't have to stop reading," she wrote. This was major. Meyer doesn't just have a lot of fans; she has a lot of fans who will read pretty much whatever she tells them to.

How did the Meyer recommendation come about? Van Straaten, like a lot of children's book publicists, makes a habit of mailing out advance reader's copies of her own favorite Scholastic titles to her peers. One of the people she sent "The Hunger Games" to was Meyer's publicist, who loved the book and -- even though it's published by another house -- urged it on Meyer. Suggesting that the creator of your company's flagship property might want to plug a competitor's new product would be unthinkable in most other industries. But at that moment, neither woman was thinking about business. They were just two readers, spreading the word.

Shares