Joe Biden, according to a report in Politico today, is interested in running for president in 2016 and has put together a seasoned staff that could help prepare him for a White House campaign.

With most vice presidents, this wouldn’t be news, but it is with Biden, who will turn 74 years old at the end of 2016. That would make him the oldest major party nominee in history if he were to seek and secure the Democratic nod, and the oldest president ever inaugurated if he were to win in the fall. This is why the popular assumption has been that the vice presidency is Biden’s career-capper.

But Biden himself has been careful never to publicly close the door on a ’16 bid, and it’s easy to understand why. The vice presidency has radically elevated his visibility and given him a level of national political relevance that far exceeds what he enjoyed in his 36 years in the Senate. This has changed the political equation for Biden. When he ran for the Democratic nomination in 2008, he was just the latest Capitol Hill lifer whose pleadings about the value of experience fell on deaf ears. As a sitting vice president, though, he’d be formidable.

Well, maybe. This is where the age factor comes in. Officially, there’s no maximum age for presidential candidates. As long as you’re still breathing, you can run. But there probably is an unofficial cutoff, a point at which the political world decides that someone is too old to be treated as a serious and relevant candidate for the presidency. Figuring out where that cutoff point is, though, is a tricky matter – and Biden would make an interesting test case.

Currently, the oldest presidential candidate ever nominated by a major party was Ronald Reagan, who was 73-and-a-half years old when he ran as the GOP candidate in 1984. But Reagan was an incumbent president that year, so his example comes with an asterisk. The oldest non-incumbent to win a nomination was Bob Dole, who turned 73 a few weeks before the 1996 Republican convention. He’s followed closely by John McCain, who turned 72 a few days before the GOP nominated him in ’08.

Against this backdrop, it’s hard to believe that Biden, who on Election Day ’16 would be just 10 weeks older than Reagan was on Election Day ’84, will be disqualified by age. Then again, the oldest presidential candidate that his party has fielded in the postwar era was Harry Truman, who was 64 and the incumbent president when he was nominated in 1948. After Truman, the next oldest was John Kerry, who was 60 in 2004.

Democrats’ tendency to pick (slightly) younger candidates doesn’t have to reflect any inherent age bias. It could just be that, unlike on the GOP side, the older candidates who have sought the Democratic nomination have generally been long shots – like Alan Cranston, who ran in 1984 at the age of 70.

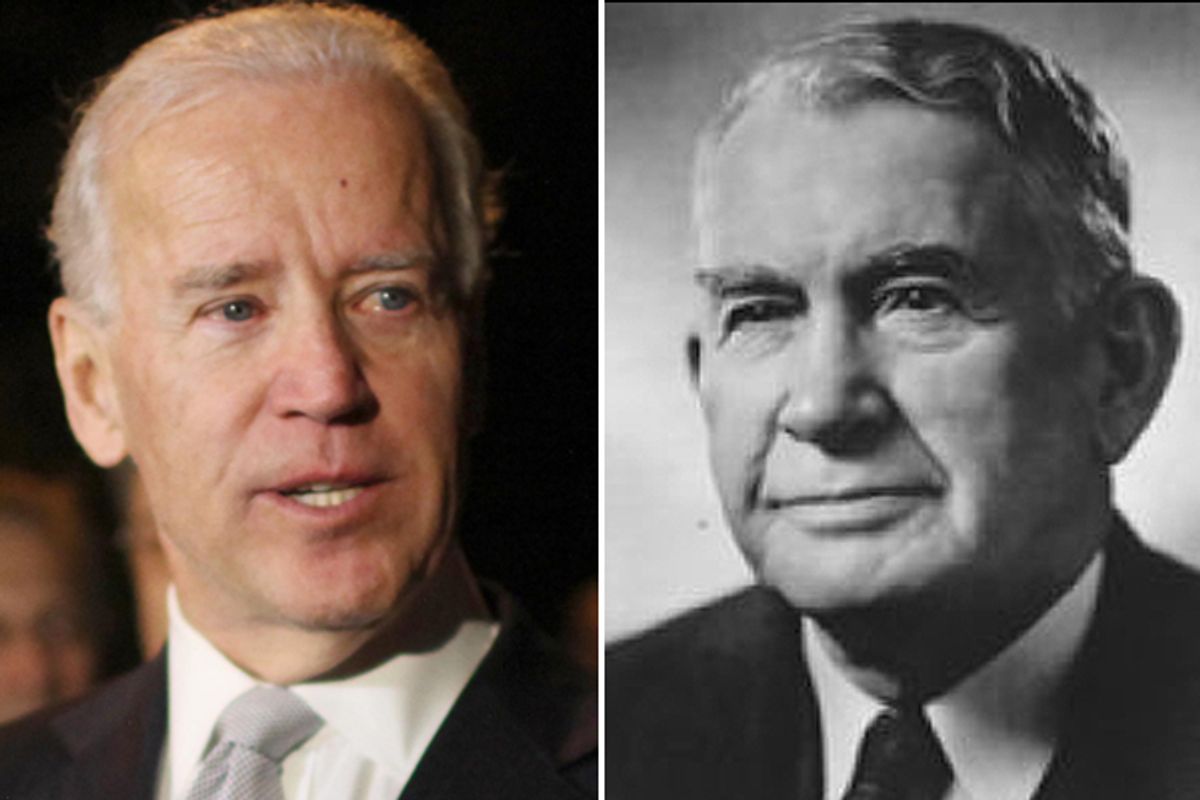

But there’s also the story of Alben Barkley, who brought to the vice presidency a political biography rather similar to Biden’s – 36 years of elected experience on Capitol Hill, 14 in the House and 22 in the Senate. Barkley, a Kentucky Democrat who made a name for himself championing the New Deal in the 1930s, won a spot on Truman’s ’48 ticket after delivering a rousing convention speech. He was 70 years old at the time, and when the Truman-Barkley ticket scored an unlikely victory that fall, it was assumed that the vice presidency would mark the peak of his career.

Barkley, though, coveted the presidency, and saw an opening four years later, when Truman, beset by miserable poll numbers and reeling from a humiliating showing in New Hampshire’s beauty contest primary, declined to run again. This was back in the days when candidates were still picked at conventions and the Democratic Party was defined by gaping regional fault lines.

With Truman out, Southerners rallied around Sen. Richard Russell, an arch-segregationist from Georgia, while Northerners flocked to Averell Harriman, a liberal New Yorker and Truman’s commerce secretary. Tennessee Sen. Estes Kefauver, whose organized crime hearings had won him a national following, commanded a bloc of delegates too. The problem was that Russell was completely unacceptable to the North, Harriman was completely unacceptable to the South, and Kefauver was completely unacceptable to Truman and other party leaders. Truman saw a solution to this stalemate in Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson, but Stevenson stonewalled him for months.

As the July convention in Chicago approached, Truman let it be known that he also considered Barkley an acceptable candidate, at which point Barkley took the quiet campaign he’d been waging for months public. On paper, he seemed like the perfect compromise candidate, a leader with national stature who was respected – and liked – by every party faction. Barkley left for Chicago convinced he was about to realize his dream.

But then, on the first morning of the convention, he sat down with Walter Reuther, the head of the UAW, and Jack Kroll, the direct of the CIO’s political operation. Barkley’s record on their issues was impeccable, but he would turn 75 at the end of the year. They told him point-blank that they considered him too old to support. Not every labor leader agreed with this assessment; John L. Lewis issued a blistering attack on Reuther and Kroll when word of their meeting with Barkley leaked. But it was enough to kill Barkley’s momentum and to force the vice president to pull out of the race, which he did that night in an angry statement.

By that point, Stevenson was off the fence and in the race, with Truman and other party leaders rallying around him. Barkley was still given a chance to address the convention. There was a 20-minute ovation when he was introduced, and as Time reported, “it was impossible not to conclude that he was making a hopeless, last-ditch attempt to bring about some improbable stampede of delegates, to set off some improbable rallying of the television audiences.” But the stampede never came, Stevenson won the nomination, and Barkley – after winning back a Senate seat from Kentucky in 1954 – died of heart attack in 1956, nine months before his first term as president would have ended.

Times have changed since 1952, of course. Life expectancies are longer and people well past retirement age play prominent, meaningful roles in American life. The Democratic nominating process has evolved too; labor leaders don’t enjoy the same clout that Reuther and Kroll did. In today’s climate, a candidate like Alben Barkley might not be vetoed because of his age.

But that doesn’t mean age no longer matters. Just think of the scrutiny – and ridicule – that McCain, Dole and even Reagan endured because they were in their 70s. Each faced countless questions about whether he was too old to run or too old to serve. Each also faces doubts from leaders of his own party, who feared that too many wrinkles and too much gray hair might make voters nervous. Age wasn’t enough to stop any of them from winning the nomination, but it was clearly on a lot of people’s minds – as it will be with Biden if he does end up running.

Shares