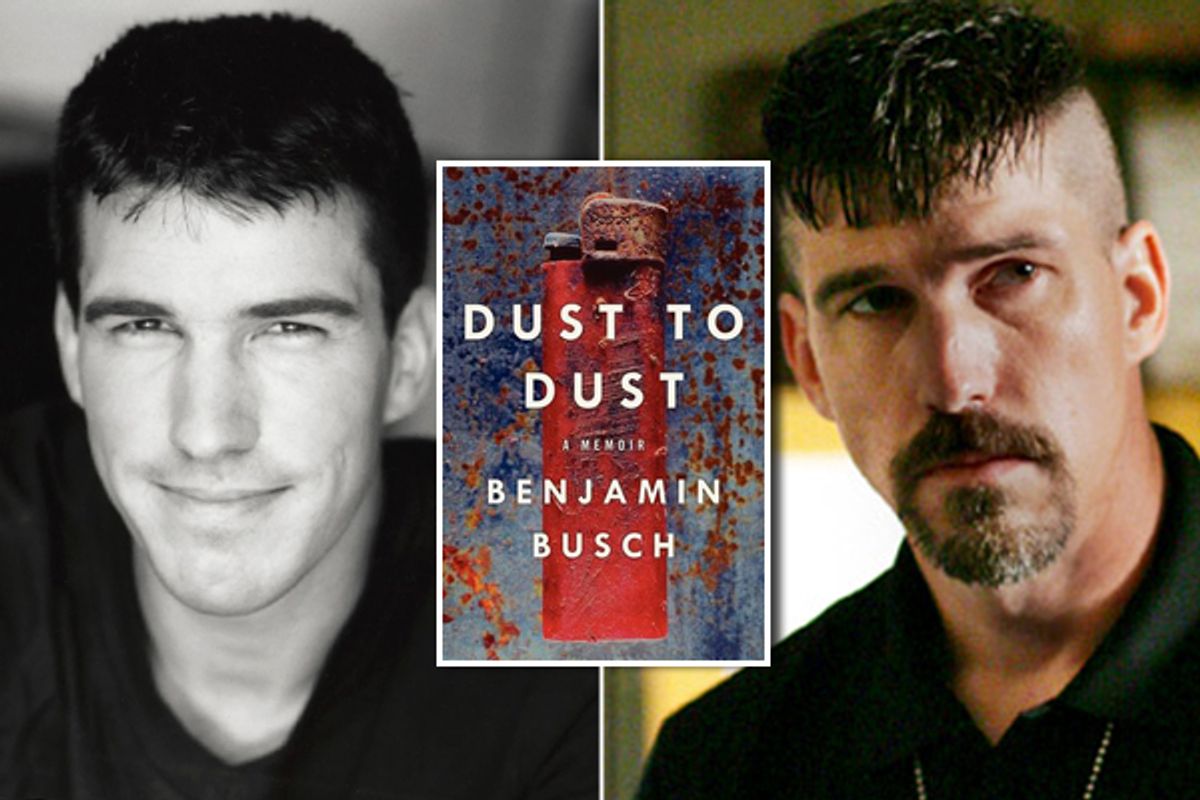

Benjamin Busch's "Dust to Dust" is a remarkable book -- part military memoir, part childhood reminiscence, and also an effort to explain his relationship with his father, the celebrated novelist Frederick Busch.

And yet it is also more than all of those things. Busch is filled with complicated and fascinating contradictions. Yes, he's the son of a famously introspective and domestic writer, who grew up in rural New York obsessed with toy guns and building massive military forts. But he studied visual arts at Vassar, where he confused everyone by joining the Marine reserves -- especially his commanders, when he accidentally announced himself in a roll call as part of the "Vassar infantry."

A man consumed with war, words and images, Busch served two combat tours in Iraq. He proved himself both exceptionally thoughtful and also terribly overconfident. In his first tour, beginning in April 2003, he was the commanding officer of a light armored reconnaissance unit, in a village near Iran. In his second tour, in an exploding Ramadi in 2005, Busch had the impossible job of trying to rebuild a town -- and gain its trust -- while insurgents and sniper fire added to the general lawlessness and lack of any power structure.

Oh, and in between those two tours, Busch returned home to play Sgt. Anthony Colicchio on "The Wire." The military man who emphasized listening to Iraqis and learning what he didn't know played a fictional Baltimore police officer of the exact opposite variety. The over-aggressive Colicchio loved nothing more than making arrests to show toughness and to pump up the Western District's stats. He's not interested in getting to know the streets he patrols, and he's disgusted by covert efforts to legalize the drug trade in a part of Baltimore dubbed "Hamsterdam."

In an interview this week, Busch said real-life frustrations in Iraq fueled Colicchio's rage. But the challenge in Iraq, he says, was making sure those frustrations never, ever revealed themselves when working with Iraqis. Both roles, he said, were essentially acting jobs. We also talked about Robert Bales and how soldiers handle pressure, where the war plans went wrong and whether the Marines need more Vassar alums.

You were a student at Vassar during the first Gulf War, the 100-hour action that pushed Iraq out of Kuwait. You write about feeling disappointed that it was over so quickly – that this looked like your generation's shot at war. You very much wanted to go to war.

I thought that. I pushed the extremes throughout my youth, as you can see from some of the small stories even as a child. I was always venturing into what I either considered unexplored territory or what I considered unwise territory to explore. And war was certainly one of those things. Its mere existence is entirely an environment of threat. Although, as you learn in war, with the randomness of death, preparation is only partially useful. Looking forward to it, you think that you could develop skills which would make you impervious. I painted myself in that idea, that I had survived the poor wisdom of my youth, and it must be because I had certain endurance. I wanted to believe that that could be extended into an environment as ferocious as war. I covered myself in a certain invulnerability in my first tour as a commander, mostly because my Marines expected it.

There's a vivid scene in the book where your helicopter is going down, and you see the side of a cliff rushing toward you, the small details of land getting clearer and clearer. But you have Marines in the back of the helicopter facing the other direction who don't know what is happening. So you just calmly smiled at them.

What else can you do in the face of death but smile.

Some people might scream.

I’m not a screamer. There’s a certain calm that comes with both a belief that you are invulnerable and a belief that you’re doomed. It leads to a lack of anxiety: One you can’t affect, and the other you can’t be affected.

And that's the change you describe during your two tours in Iraq. The first time, there's an eerie confidence. But the second time, death is omnipresent.

Yes, between the two tours that became very pronounced. My first tour I was wearing it for show; I created my own myth and believed in it. My second tour I was wounded almost immediately and we were taking incredible casualties and Ramadi was just a caustic environment in 2005. It was entirely random; every day you expected that it was going to be your day. We almost had this fatalistic humor about it all. We’d walk out the door and say, "Oh, I’m probably going to be killed today, so you can have my uniforms." People weren’t surviving.

This is post-insurgency, and in the capital of the Sunni province of Anbar. It was a very bloody time, and you suggest our presence didn't help, which in some ways is a startling admission from a Marine.

It was teeming not just with insurgents -- actual Sunnis which were fighting for their own destiny -- but it was also overrun with Syrians who were real pure jihadists. They came across the border to fight and die – they came there for us. Many of them were funded by Saudis. So there was a strange triangle of danger created all around our mere presence. And what we would look at was the families. There were children living there and parents who wanted what everyone wants – a secure day, food on the table. And not to fear that something collateral will happen to them, either by insurgents or by us. It was hard to watch that every day, knowing that they were under threat because we were under threat. And that our job was to protect them and we really couldn’t.

Let me back up for a moment. Your memoir has nine chapters, structured among elements like water, metal, stone and blood. You recount stories involving those materials from your youth, and then connect those materials to your war stories. So how did your childhood prepare you for what you saw when you weren't playing games?

Endless fascination. I think it was endless fascination that prepared me for everything in my life. I was always paying attention. I was put here to observe and build upon my fascinations.

You make it sound simple. But there's another scene in the book where you are called to mediate an emergency council meeting in Jassan. Water had been diverted to Saddam Hussein's family. The town wanted a pipe sealed so their water flow would improve. The people did not know what to do, and insurgents were threatening the village's leaders and sent a message during the meeting that they would also kill you. How does a young American in that situation know what to do?

It's my Lawrence of Arabia moment.

It's also a moment where you teach the meaning of democracy. You empower them to put the matter to a vote, and then act. You see people hungry to solve problems together, and excited to find the power within themselves to do that. That's in some ways what we said we would do there -- and exactly what didn't happen often enough.

It was my place not to impose that, but to let that native urge be successful. I just felt very early that they wanted direction, and the worst thing that I could do would be to give it, because that would make me in charge. That would make me the ruling class. What had been removed was any sense of structure – the Baath party had been dissolved at that point, and had not been replaced with anything. There was a huge vacuum and all that had been put into it was us. And I knew that our mistakes would be made by creating a dependency upon a new state order that was perhaps not sustainable. I had nothing to offer except advice and bullets. That’s what I had. We couldn’t even get our mail at the time. What I wanted to do was find native solutions to native problems that I could only reinforce their answers to their problems, in some ways. And that was a big moment I wish I could have celebrated in some ways because it was their choice and it was just that brief moment where they felt like they were in charge of their destiny – they felt like they had done something. They had the power to achieve justice, and they did it against all the odds. We had to replace rule of law in a place that is entirely lawless.

So you pay attention. I just followed my fascinations. Why is the water not running? Where does the water come from? Let’s follow that. And we did. You begin to reverse engineer everything just by seeing what’s wrong at the end. I wouldn’t say that I was good at anything.

Good questions. Too bad we didn't ask them more often.

We could have saved a lot of time and a lot of loss if we had done so. What I feel the most regret about is that I left those people. We had that place almost stabilized in some ways, and though it was not in any way efficient or in any way without corruption, there was a possibility of being quietly transformative in some of those communities.

How do you see what went wrong?

We tried to define them. It’s what we do. We’re Americans. We find ourselves in a position that’s generally comfortable and our vision can only extend so far as us, and who wouldn’t want to be like us. So, if we just offer this, then it will be accepted and embraced. We don’t have a lot of respect for cultural traditions because we barely have any.

And honestly, our own history, if you watch how we achieved our great comfort, it’s pretty ugly. We’d like to criticize everyone for their stages toward democracy but if you look at ours – we didn’t let women vote, we didn’t let blacks vote, we had slaves. We had issues. We eradicated an entire native population almost. I went into the place knowing that I was the one with the least information, and so it was my job to spend as much time listening and not talking as I could. I wanted to make sure I kept track of the details, the names. I was rebuilding family trees because the environment was built out of family trees.

Unless you’re going to come in there like the British empire and establish infrastructure and reform an entire place in its image, then you’re going to be wholly ineffective. We are definitely not the British empire in the way that we do business. We went in there awkwardly, we built mistakes upon mistakes. And after a while, you know, we wore ourselves down being wrong about things. It just took a little perspective, and some specialists. The people in the State Department knew all about Iraq. I would have liked to have had them in my vehicle.

All that failure, all that pressure, the consecutive tours. Not everybody handles pressure the way you were able to. What do you think happens when a soldier snaps, like Sgt. Robert Bales in Afghanistan, and allegedly goes on a shooting rampage and kills 17 people.

I can’t diagnose him. We have people that do horrible things all the time. Everyone deals with stress in their own way. There were ideologues over there. There were people who were on crusades. You just name it – look at everyone’s background.

Is this the right way to put a military together? When you look at the background you had, and the very different way you approached problem-solving and building relationships with people, those don't necessarily seem to be the skills most valued by the military right now. You were a visual artist from Vassar. You probably had many cultural issues to overcome. But would a more diverse military be beneficial? Even some sort of mandated public service of some sort

What I found intriguing was that I met America in the Marines. At Vassar, I met a certain intellectual group. Vassar doesn’t teach you how to do anything. Literally. You come out of Vassar with no skill other than that if you find yourself in any situation you’ll be able to think your way out of it. It’s a critical thinking environment. To constantly question, to constantly try to resolve, and to resolve by not talking over the problem but by engaging in it. Collectively in some ways. The military obviously has a very hierarchical system, but I didn’t see them any differently. I took the discipline of critical thinking, much to the chagrin of certain people, and I employed it.

Now that led to its own kind of hubris in your second tour, when you thought what had been effective among the Shia might also work with the Sunni. It didn't.

I said, well, I don’t understand anything that’s happening here, which should tell me something. Shut up and find out. I deluded myself into thinking that because I had been effective in that area, which was very rural, Shia, on the Iranian border, with completely different feelings, that when I went for my second tour in Ramadi, the opposite side of the country, Sunni, I thought I could apply these great collective, cooperative ideas of building a city to a place that was a shooting gallery. And I was exposed for being the most wrong person, ever. It was just one step short of delusional that I could take these ideas and apply them effectively to a place, thinking, Well, this has been effective in a small scale, on a small range, with almost no money. We repaired buildings, we established critical infrastructure, we fixed water lines. We did an awful lot of stuff in a small place and they liked it.

With the irony, of course, that we fixed what we blew up.

Right. I thought that if you give something to someone that they realize is of great value to them, then they will defend it and, in doing so, they will embrace some of the stability that comes with preserving things instead of destroying them. We knew very well what the Taliban did and what the insurgents could do, which was destroy things. They didn’t build things for people; they blew them up. Our message was, “We didn’t do that.” And of course, in order to fight them, we blew things up. So our message was lost in our own struggle, and we never could achieve the support of the locals because we could prove nothing. We couldn’t give them the one thing that was needed for all these things to be effective, which was security, peace. We couldn’t do it. And because they knew we couldn’t do it, they were forced to side with those who would use extreme measures.

"Hopelessness" is certainly a word that comes to mind. I mean, we fought the city every day, as one captain said when we were there. You don’t fight the Battle of Ramadi, you fight Ramadi every day.

An impossible bureaucracy, corrupt institutions, intractable problems -- it's almost like a David Simon TV show. And in between tours in Iraq, you established an acting career, and played a Baltimore policeman on "The Wire." How did one experience affect the other?

Sgt. Colicchio fed off that second tour of Iraq where I was so frustrated. Colicchio is the opposite, he has a very black-and-white sense of justice. There is no gray for him, and of course, Iraq was entirely gray. So I got to air all the things I had to bury while I was there.

What was the timeline like on the acting roles, and your military service?

Interestingly, I had just come back from my first tour when I got the role of Colicchio. And for a year, 2004, I did Season 3. Immediately at the end of the filming schedule, I went to Ramadi. For 2005, I came back just in time for the beginning of Season 4 and rushed to grow out some hair on my face. It was literally at the end of one experience and the beginning of a very different one.

How do you handle that psychologically -- to go from a real war zone into playing a police officer?

It was all an acting of a certain kind. When you play a role, there is some of you in it, and the rest is what you’re burying yourself in to create a character. I did that in Iraq. I didn’t think I could be killed. I had to prove that by acting that way. And I did the same thing with Colicchio; Colicchio was airing a lot of frustration I truly felt, that I kept to myself, and he gave it a voice. So it’s interesting that I think the war informed Colicchio in some ways, and then going back, I was once again placed in that environment where I had to create a certain person who was both real and partially imagined to deal with that environment. I couldn’t actively and visually be frustrated with Iraqis, because that was insulting. Even if they were saying the most outrageous stuff imaginable. It’s an area of conversation, most of which is a lie. Asking questions about the lie, you begin to get pieces of the truth, and eventually, you create something close to what’s really going on.

Shares