News of Thomas Kinkade's death arrived on the same day I received in the mail a vintage teacup on which I had spent a ridiculous amount of money. It has a cottage painted on it. Kinkade, whose work has long exerted a morbid fascination for me (to the concern of all my friends), specialized in cottages. So some part of me understands the appeal, I guess, but, damn: Those paintings make my corneas hurt. And yet, I could barely stop looking at them.

Kinkade was only 54, and his family told the media that he died of "natural causes." This comes after years of reports of drunken public misbehavior: cursing at people who tried to save him from falling off bar stools, heckling Siegfried & Roy, grabbing a woman's breasts at a publicity event and, most memorably, urinating on a Winnie the Pooh statue at the Disneyland Hotel while proclaiming, "This one's for you, Walt!" There were DUI arrests. Also, his manufacturing company declared bankruptcy two years ago, and former franchisees of the once-ubiquitous Thomas Kinkade Signature Galleries won settlements against him for fraud.

That's quite a fall for a man who frequently spoke of his Christian faith and family values when asked to comment on the mammoth success of his brand in the early 2000s. "When I got saved, God became my art agent," Kinkade explained in a 2004 video. He went from a childhood in Placerville, Calif. (invariably characterized as "hard-scrabble") to an apprenticeship selling his work in supermarket parking lots to his apotheosis as the nation's "most profitable" artist, the Painter of Light™, and multimillionaire. He was profiled in the New Yorker by Susan Orlean.

I first learned about the dark side of the Painter of Light™ -- sorry, couldn't resist that one -- when I reviewed "his" novel, "Cape Light," in 2002. The novel, first in a series, was produced much as his paintings are: by a semi-industrial process in which low-level apprentices embellish a prefab base provided by Kinkade. He wasn't the only artist to work in this way; he wasn't even the only novelist. To the best of my knowledge, his novels -- heartwarming, fuzzily pious tales of small-town life -- have been coming out ever since, one more facet of a lifestyle brand that, at its most ambitious, included an entire Thomas Kinkade-themed housing development.

My review was just a goof intended to amuse Salon's readers, but after it appeared, I began to receive emails from people who had sunk their life savings in Thomas Kinkade Signature Galleries (essentially, mall and shopping-district outlets for his prints) and been fleeced. I didn't really understand how the financial architecture of Kinkade's gallery empire worked, and I sure didn't share their taste in wall art, but these people struck me as decent and sincere. They'd believed in Thomas Kinkade -- not just in the man or the company, but in the ethos supposedly represented by his work, one in which (to quote Kinkade's introduction to "Cape Light") "people have the time to savor life’s simple pleasures" and lead "deep, satisfying lives."

My conversations with these victims made me uneasy. Was there some relationship between the franchisees' naivete, perhaps even their willful self-delusion, and their terrible taste? Was it hopelessly snobby to wonder that? What about Kinkade himself? He seemed to be at best a hypocrite and at worst a crook. Was there a meaningful connection between his bad conscience and his bad art? German thinkers of the 1930s would have said so, and they had plenty of opportunity to observe bad fascist art up close. Hermann Broch maintained that someone who chooses to make kitsch is "ethically depraved, a criminal willing radical evil." The novelist Milan Kundera believes kitsch to be the natural expression of totalitarianism. That's a lot of moral weight to place on a bunch of garish cottage paintings, but Kinkade was always the first to present his work as a form of ideology.

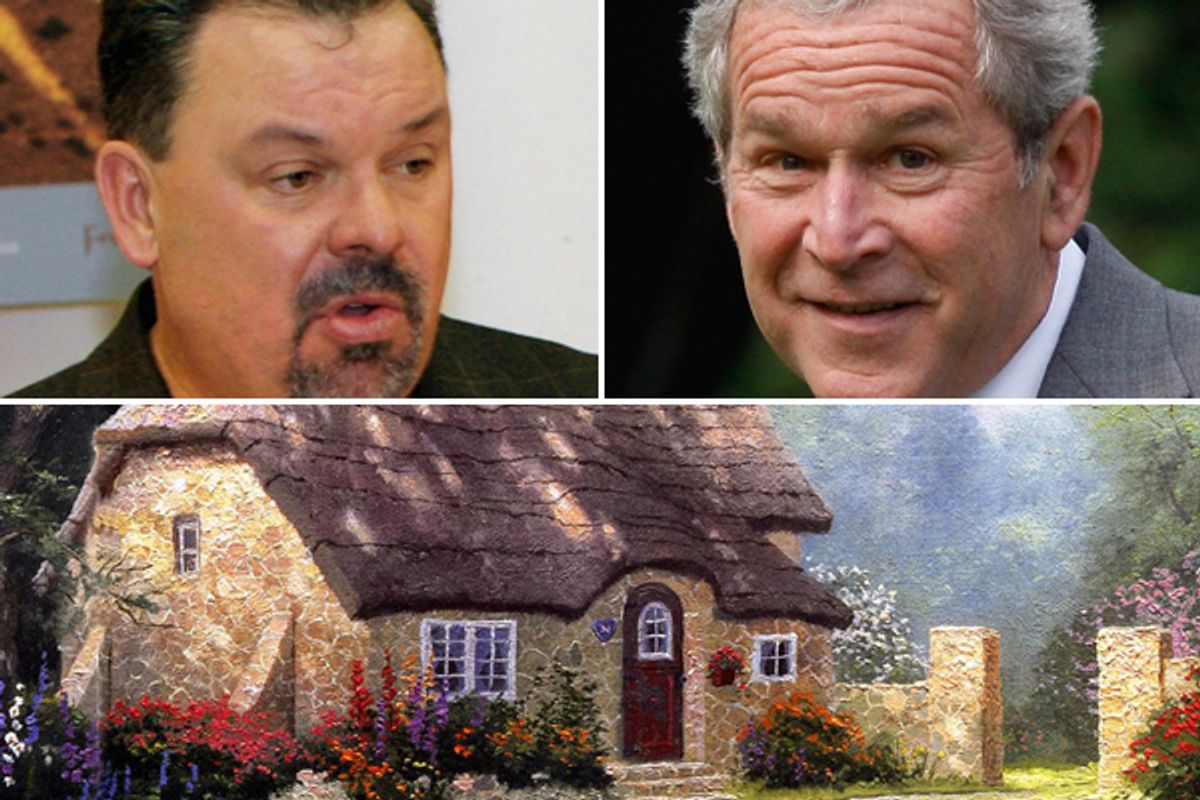

I felt compassion for the ripped-off gallery operators, and at the same time I was aware that quite a few of them had probably also fallen for the similarly sanctimonious, bogus folksiness of George W. Bush, thereby subjecting our nation to one of the worst presidents in its history. Kinkade and Bush struck me as of a piece, probably because they had both borrowed from Ronald Reagan in promising that we could get back to a better way of life that never existed in the first place. In nearly every encounter with the press, Kinkade delivered a diatribe against the art-world "establishment" that had shut him out. They were "elites" touting unfathomable, downer junk to hardworking people who needed uplift instead. Art snobs were the aesthetic counterparts of the so-called liberal elites, a group that surely included me.

At the same time, I must admit that I, too, like a cottage. Granted, I like the stylized, art-deco kind painted on bone china, rather than the insanely detailed and phosphorescently lit specimens in Kinkade's pictures. And I'm in little danger of equating my new teacup with a Brancusi just because it's cheerier. Nevertheless, I suspect that my idea of what's pleasing about a cottage isn't too different from that of Kinkade's fans: an aura of harmless coziness, of modest domestic beauty and comfort not too cut off from the past. It's as if we're speaking the same word, but in different languages.

I suspect this is why Kinkade's paintings have exerted their weird, hypnotic effect on me. They are so preposterous (especially the stream-side ones; he really needed to sit down with an architect and go over the basics of drainage), so awful. And yet I can still detect -- beneath that cacophony of hollyhocks and cobblestones and snapdragons -- the whisper of something intelligible. I'm pretty sure I know why the hordes of Kinkade collectors love his work, even if I don't like it myself. Kinkade's paintings are irredeemably false, like all kitsch, but through them you can just barely glimpse the honest desires they seek to exploit, sinking under the dreck.

Kundera defined kitsch as "the absolute denial of shit," meaning it offers an airbrushed, sterilized, sentimentalized view of the world. From that, it doesn't necessarily follow that art wallows in shit, but art doesn't exist for the primary purpose of denying it, either. Kitsch is, first and foremost, a lie; its very existence is founded on bad faith.

Kinkade, like Bush, peddled a falsely simplified image of the world -- one without mildew or flooded basements, for one thing -- which, no surprise, turned out to be plastered over a whole lot of stinky stuff. The true believers, the ones who bought into these men the most during the 2000s, ended up paying some of the highest prices, from the Kinkade acolytes who invested in his gallery Ponzi scheme to the working-class red-staters who sent off their kids to die in a pointless war. Bad taste, harmless as it may seem, can end up costing you a lot.

Further reading

Los Angeles Times obituary for Thomas Kinkade

Susan Orlean's 2001 profile of Thomas Kinkade for the New Yorker

A 2006 Los Angeles Times story documenting Kinkade's business problems

Laura Miller reviews "Cape Light," a novel by Thomas Kinkade and Katherine Spencer

Shares