When Ann Romney's status as a stay-at-home mom became a political football in the last week, she went on Fox News and emphasized that it was all about choices, saying "We need to respect the choices that women make.” But at a 1994 campaign event, Ann Romney told low-income women in no uncertain terms that they should stay at home with their kids, according to Judith Dushku, a prominent Mormon feminist who knew the Romneys over several decades and attended the forum. It was also a contrast from Mitt Romney's position at the time -- and as recently as this January -- which favored bringing low-income mothers into the workforce in exchange for welfare benefits.

The topic of that 1994 event, headlined by Ann Romney and the Children's Defense Fund's Marian Wright Edelman and held during Romney's Senate race against Ted Kennedy, was women and children’s safety and rights, according to Dushku. The audience, she recalls, was predominately African-American and Latina women with young children in tow. They asked about welfare benefits, as reform and "welfare-to-work" were hot topics at the time. Ann Romney’s position, according to Dushku, was to be a stay-at-home mom at all costs -- consistent with Mormon doctrine, if off-message for the campaign. When one audience member asked about community service, Ann Romney said, “I would just say no...You have no business going around in your community when your children are young,” Dushku remembers. She says now, “People almost booed and hissed.”

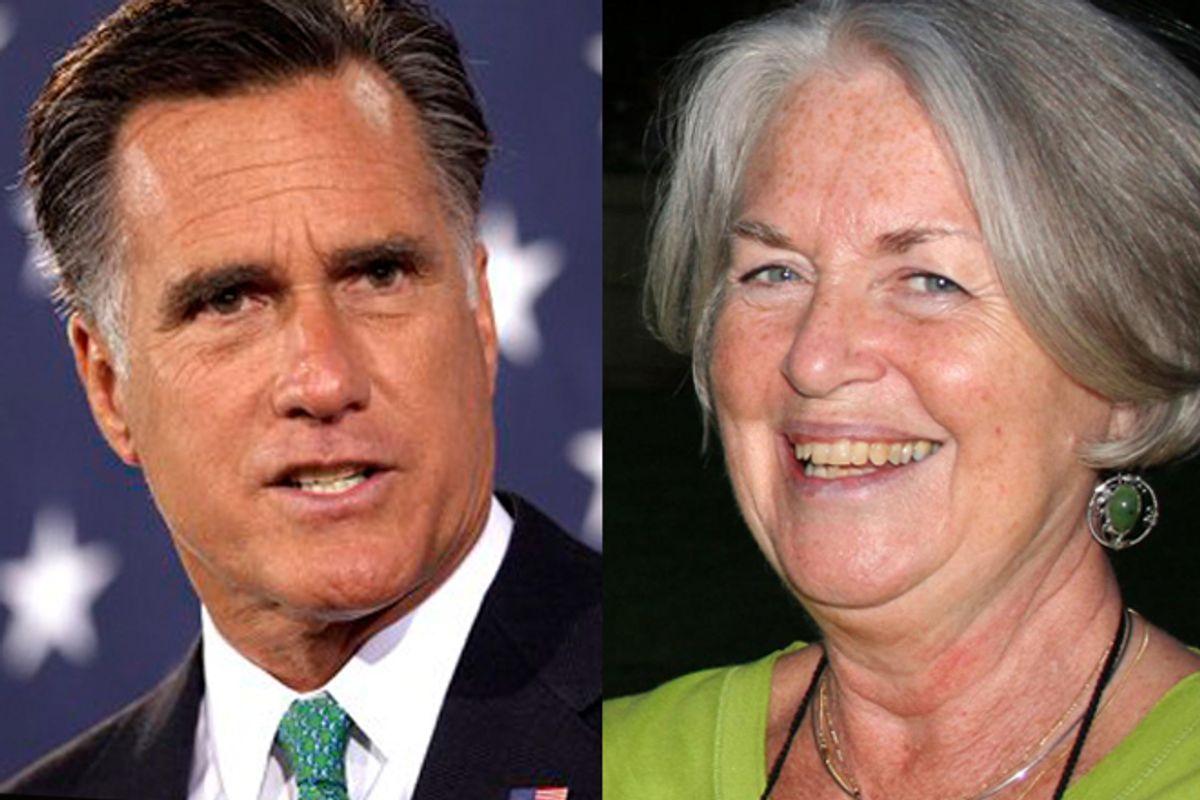

Dushku is a professor at Suffolk University who for many years was a member of the suburban Boston congregation where Mitt Romney became bishop, occasionally butting heads with him over issues of women in the church. Though in previous campaigns she has voiced her concerns to the press, in an interview with Salon Wednesday, Dushku said she has been ambivalent about granting more interviews about Romney. Mormons are "harmony-seeking," she said. But she described herself as "irritated" by last week's "war on moms" rhetoric, and in the conversation, Dushku expressed stinging criticism of Mitt Romney's attitudes toward women.

But she also zeroed in on Ann Romney's position from her husband's first Massachusetts campaign. It was Romney’s attitude that really struck Dushku: “She acted like it was such an easy question to answer. She didn’t understand [staying at home] was a luxury that only a few people can afford.” Dushku says she and a friend who attended actually felt sorry for Romney, coming away thinking, “Ann just does not understand these issues.”

Of course, Ann Romney was essentially repeating what the Mormon church still proscribes for women, though that script has been challenged by Dushku and others. As the women's movement blossomed throughout the 1970s, Dushku and fellow Massachusetts Mormons began questioning gender roles within the church. They even founded a Mormon feminist journal, Exponent II, that is still published. Ann Romney stayed on the sidelines during those debates, though Dushku couldn’t recall her explicitly commenting on their aims.

Mitt Romney was clearer in his reactions. “Mitt had an attitude of, ‘Why do you have to stir things up? It has nothing to do with the church and women should be satisfied with what they have,'" Duskhu says. When Dushku was a divorced mother of four, she says Romney “just thought that anybody that wasn’t married to someone who can support them was just almost too unusual to consider in any collegial way.”

Other Mormon feminists who knew Romney during that era also have less-than-rosy memories of his attitudes toward women. Helen Claire Sievers, who also worked on the early days of Exponent II, told the National Journal that she once told Romney that spousal abuse was more widespread than she would have guessed. Romney replied that “he was pretty sure it wasn’t happening. … There was a man who told Mitt that he was abusive to his wife, and Mitt said, 'No, you’re not.' It was so hard for him to understand what was thought of as spousal abuse.” He did, however, agree to meet with women involved in the Mormon feminist community and to try to work with them.

At least two Mormon women who had been involved in feminist causes, Elisabeth Calvert-Smith and Barbara Taylor, went on to work for Romney’s campaign or join his administration. Calvert-Smith declined to be interviewed, and Taylor did not respond to a request. But Taylor, who later worked as an executive assistant to Romney, told the Washington Post in November that though Romney initially “thought we were just a bunch of bored, unhappy housewives trying to stir up trouble," he had “evolved." Romney, she said, is "an entirely different person now.”

Dushku seems unconvinced. When Romney said on the campaign trail that he knew about women’s concerns because his wife had told him, several Mormon feminists told me it echoed the way things are done within the LDS church, where women and men move in separate spheres. “I would agree,” said Dushku when I ran this by her. “I think Mitt has never learned how to talk to women.” What about the women who worked for him in the statehouse – where, his campaign has pointed out, he employed women in record numbers – or at Bain? “I think he did that under pressure, to keep that issue at bay, because he knew he was vulnerable in that area,” Dushku said.

“He’s not a man who has a moral core," she said. "He’s very loyal to the Mormon church, pays his tithing, is faithful to his wife, but he doesn’t have a set of core values you can count on.”

Dushku says she saw that firsthand in what is probably her most high-profile clash with Romney – when she went to the Boston Globe during that 1994 Senate race with the story of her friend, later identified as fellow Exponent II member Carrel Hilton Sheldon. Early in her pregnancy, Sheldon’s doctors discovered that Sheldon had a dangerous, potentially life-threatening blood clot. Sheldon’s Mormon stake president, a doctor, counseled her to have an abortion, which was also her preference, and to care for her four existing children. Romney, however, “regaled me with stories of his sister and her retarded child and what a blessing that child had been to the family. He told me that ‘as your bishop, my concern is with the child,’” according to Sheldon. Dushku said in a 2007 interview that Romney said “something to the effect of – Well, why do you get off easy when other women have their babies?’” So when Romney began claiming that he was pro-choice in his 1994 election, Dushku told the Globe, “I went to his office and I congratulated him on taking a pro-choice position. And his response was – Well, they told me in Salt Lake City I could take this position, and in fact I probably had to in order to win in a liberal state like Massachusetts.”

Today, she says, the encounter with Sheldon is “a sign that Mitt thinks once he’s made a decision, it’s the right decision. His style has always been one of telling people exactly what is right or wrong. He’s not someone to engage people in conversation. He’s a person who comes to a conclusion, is emphatic about it, and he’s not interested in dialogue and exchange.” Dushku, a political scientist, said Romney was bewildered in that race when reporters called her for insights on him, because he had never taken any interest in her work. “He would say, ‘Why would anybody call you?’” And when the Boston Globe ran the Sheldon story, Dushku told Salon, “He said, ‘Well, how did you come out from under a rug just to attack me?’”

“We’d never had a real confrontation until after the campaign, when he blamed me for helping him lose,” Dushku says now. “Mostly he was just a dismissive person who felt like he had the right to decide for everyone what was the right way to be a Mormon.”

Indeed, one biography of Romney, Michael Kranish and Scott Helman's “The Real Romney,” has Romney telling Dushku, even before the split over abortion and the election, "I can tell you one thing: You're not my kind of Mormon." After Romney was elected governor of Massachusetts in 2002, according to Ron Scott’s Romney biography, Mormon leaders essentially redistricted the wards so Romney and Dushku would never cross paths. “To some, this dextrous and nearly transparent maneuver became known as the Dushku gerrymander, an unrequested courtesy extended to their former stake president Mitt Romney and his wife, who would never again have to be face to face with Judy Dushku while they worshiped.”

Shares