Nobody can complain that ideas are missing from the debate about American tax policy, which will heat up as the 2013 expiration of the Bush tax cuts approaches. There are plenty of competing ideas for tax reform. Unfortunately, most of the ideas are misguided. America needs radical tax reform — but of a kind different from the conventional proposals offered by the center, right and left.

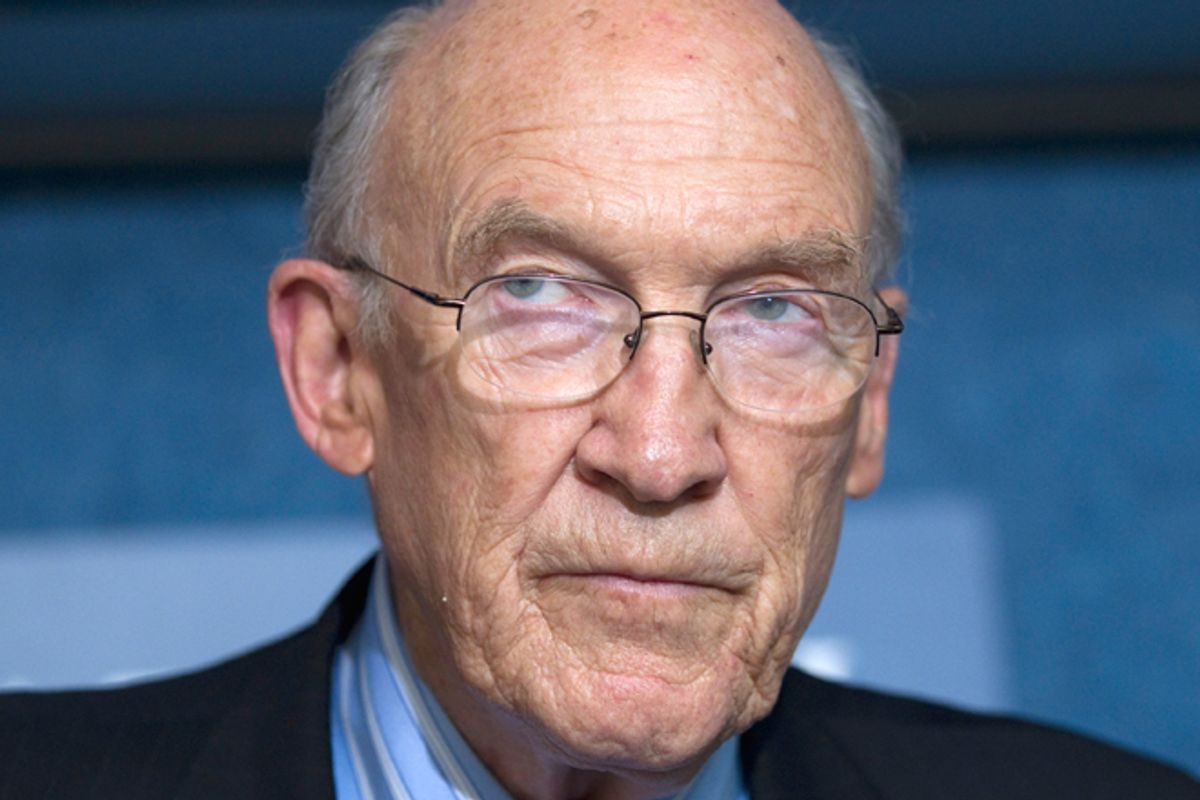

The dominant approach to tax reform is considered to be “centrist” and symbolized by, among others, the Simpson-Bowles plan.

In what is advertised as a grand bargain between the right and the left, tax rates will be lowered, to appease conservatives, in return for closing many tax expenditures or “loopholes” (for some reason this is presented as a concession to liberals). Revenue that would otherwise be sheltered from taxation by the abolished loopholes would, to some degree, raise overall federal revenue collection, even with lower rates.

Allegedly centrist tax reform plans like Simpson-Bowles are presented by the media as nonpartisan compromises by serious, thoughtful, public-spirited experts willing to speak truth to selfish special interests. In reality the Simpson-Bowles plan and similar schemes are best described as center-right. Generally these plans call not only for closing loopholes that disproportionately benefit the rich, like the home mortgage interest deduction, but also for cutting essential government benefits for the middle class, like Social Security and Medicare.

Alan Simpson famously mocked Social Security as “a milk cow with 310 million tits.”

The bargain at the core of plans like Bowles-Simpson — lowering income tax rates while reducing tax expenditures — isn’t a genuine bargain at all. If it is a good idea to raise needed revenue by closing loopholes while lowering income tax rates, why not raise even more revenue by closing loopholes without lowering income tax rates? This kind of “grand bargain” is not based on give-and-take among two sides equally flexible and willing to bargain. Instead, it requires the center and the left to engage in unilateral surrender to extortion by the uncompromising right.

If Simpson-Bowles represents the center-right in the tax debate, the radical right is represented by flax-tax plans like the “Fair Tax” that would replace most or all federal taxes with a single national consumption tax with a single rate. A national consumption tax ought to play a role in federal tax reform — but as an addition to the mix of taxes, not as a replacement for all other taxes. A single flat tax would be extremely regressive, dramatically shifting the burden of taxation from the rich to the middle class and the poor.

Compared to the center-right and the far right, the American left has been relatively uninterested in devising plans for tax reform. One reason is the justified focus of liberals on what the political scientist Jacob Hacker calls “pre-distribution,” like the growing pre-tax inequality highlighted by the Occupy Wall Street movement. Another factor is undoubtedly the fact that, unlike many conservatives, progressives do not believe that tax policy is all-important for economic growth, to the exclusion of other factors, like public investment, trade policy, energy policy and education. To the extent that there is a consensus on tax reform among American progressives, it would seem to combine higher taxes on the rich with more tax breaks for the middle class as well as the poor — the “Buffett Rule” (a minimum tax on millionaires) plus an expansion of the earned income tax credit, for example.

Unfortunately, when it comes to taxes, many American progressives think with their hearts, rather than with their heads. They want a welfare state on a European scale, but ignore the fact that European social democracies do not rely for revenue primarily on steep income taxes. Instead, the most generous European welfare states derive their funding from three kinds of taxes: income taxes, payroll taxes and a consumption tax, the value-added tax (VAT). In contrast, the U.S. federal government derives its revenue chiefly from only two taxes: the personal income tax and the payroll tax. In the U.S., consumption taxes are used by state and local governments but not by the federal government.

Michael Graetz of Columbia Law School points out that “the United States is a relatively low-tax country, but not with respect to income taxes ... We typically collect about 12 percent of GDP in corporate and individual income taxes, while the OECD nations average about 13 percent. The biggest difference is that most other nations rely much more heavily on consumption taxes than we do: 11 percent of GDP in the OECD compared to about 5 percent in the United States. Indeed, we are the only OECD nation that does not impose a national level tax on sales of goods and services.”

This raises the possibility of a fourth option for American tax reform, distinct from the phony centrism of Simpson-Bowles (closing loopholes while lowering rates for the rich and cutting entitlements for the majority), radical conservatism (the single flat tax) and conventional progressivism (relying for more revenue chiefly on higher personal income taxes combined with bigger tax credits). The fourth option would reject the goal of revenue neutrality and acknowledge that, in a nation with an aging population, federal taxes can and should be permanently increased to pay for Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. (These, like the rest of the American healthcare sector, need to be made solvent by price reduction and price regulation, not rationing). Much or most of the needed additional revenue should come from the adoption by the federal government of a VAT. A federal VAT’s revenues could be shared with state and local governments, partly replacing existing sales taxes.

This approach to radical tax reform could take more liberal or more conservative forms. In a 2002 article and a 2007 book, Michael Graetz has proposed one version, a “competitive tax plan” (CTP), which the Urban Institute recently analyzed.

The Graetz plan would use the revenues from a VAT to eliminate income taxes on Americans who make less than $100,000 a year. It would also lower payroll taxes, by means of payroll tax rebates that would offset the regressiveness of the VAT. As the tax expert Bruce Bartlett notes, the Graetz plan would eliminate popular support for income tax expenditures by eliminating income taxes on most of the middle class: “The important thing is the basic idea of avoiding a frontal assault on tax expenditures that is likely to make trench warfare seem tame by comparison and instead just make them irrelevant to the vast majority of Americans.” A VAT can also be used to cut corporate income taxes that discourage production in the U.S., an option that the Urban Institute and the New America Foundation’s Economic Growth Program analyzed in a 2010 study.

The Graetz plan is revenue neutral but it could be tweaked to raise more revenue overall or to be more progressive. Any plan that attempts to compensate for the regressive nature of a VAT by means of credits or rebates for working Americans that would be administered through the payroll tax would necessarily reduce payroll tax revenues for Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. But that is a point in its favor. In a society in which more and more of the gains from economic growth are going to capital, rather than labor, it makes sense to shift from a system in which social insurance relies solely on payroll taxes to a new system in which it relies on a mix of payroll taxes and higher taxes on the consumption or non-wage income of the rich. Medicare has always been funded in part by payroll taxes and general revenues. Funding Social Security by general revenues or other dedicated taxes, in addition to payroll taxes, might permit not only income taxes but also payroll taxes to be permanently reduced for the majority of working Americans.

This approach to tax reform should appeal to progressives and genuine centrists for another reason. It would almost certainly doom the conservative project of replacing public social insurance programs with tax credits or private accounts subsidized through personal income tax expenditures, because only affluent Americans would pay income taxes and middle-class voters would no longer enjoy the benefits of those programs. Tax reform that limited income taxation to the affluent few could thus build support for the replacement of the unfair and inefficient private welfare state run through the IRS — a system that includes 401Ks, IRAs and tax credits for employer and individual health insurance — with a simpler, cheaper, more efficient system of public provision or public utility regulation in the fields of retirement security and healthcare.

Conservative Democrats and moderately conservative Republicans, masquerading as “bipartisan centrists,” have signaled that following this fall’s election they plan to push for the passage of tax reform along the lines of the Simpson-Bowles proposal in the lame duck Congress. But the American people deserve, and the American economy needs, a better option for tax reform than the pseudo-centrist proposal of further lowering tax rates on the rich while eliminating or capping tax expenditures. Something along the lines of the Graetz plan that would use a federal VAT to cut both federal income taxes and payroll taxes for the working majority of Americans while providing adequate revenue for a twenty-first-century government is the truly radical tax reform that America needs.

Shares