In the fall of 2010, three former students at Everest College, a for-profit career school in Salt Lake City, sued their school's parent company, Corinthian Colleges, alleging that admissions officers had misrepresented both the costs of the school and whether class credits earned at Everest could be transferred to other educational institutions.

A 13-page affidavit filed in the case by a former admissions officer, Shayler White, described a high-pressure recruitment process in which prospective students were barraged by phone calls multiple times a day and hustled through financial aid paperwork. With his employment contingent on meeting a strict enrollment quota, White made as many as 600 calls a month, and was, he said, instructed by his superiors to use bullying psychological tactics, to ask questions "designed at putting down the prospective student" and "making them feel hopeless."

"The ultimate goal was to essentially make them wallow in their grief, feel that pain of having accomplished nothing in life, and then use that pain as their 'reasons' to compel the leads to schedule an in-person meeting with an Everest admissions representative."

Representatives of Corinthian Colleges dispute White's assertions. Kent Jenkins, Corinthian's current vice president for public affairs, deflected a question asking if White's account accurately represented Corinthian's recruitment process by noting that there has been no final disposition of the Utah suit. "There have been absolutely no court rulings that support any allegations" in the affidavit, he wrote in an email. "There simply is no 'there,' there."

But generally speaking, there's little question that an obsessive focus on constantly boosting enrollment is crucial to survival in the for-profit college world. Sky-high withdrawal rates plague the industry. It's not uncommon for the biggest for-profits to enroll as many new students during the course of a single year as originally signed up for classes at the beginning of the year, a phenomenon referred to as "enrollment churn." For example, Corinthian had 71,246 students in July 2008, enrolled 120,638 new students during the following year, but ended up with only 89,479 by June 30, 2009. Recruiting all those new bodies costs a lot of money. In 2009, Corinthian spent almost a quarter of its $1.3 billion in revenues on advertising and recruitment.

"They are, by and large, a marketing operation," Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., said in a speech on the Senate floor last September. "Bring the students in, sign them up, bring in the federal dollars; bring in more students, sign them up, bring in more federal dollars."

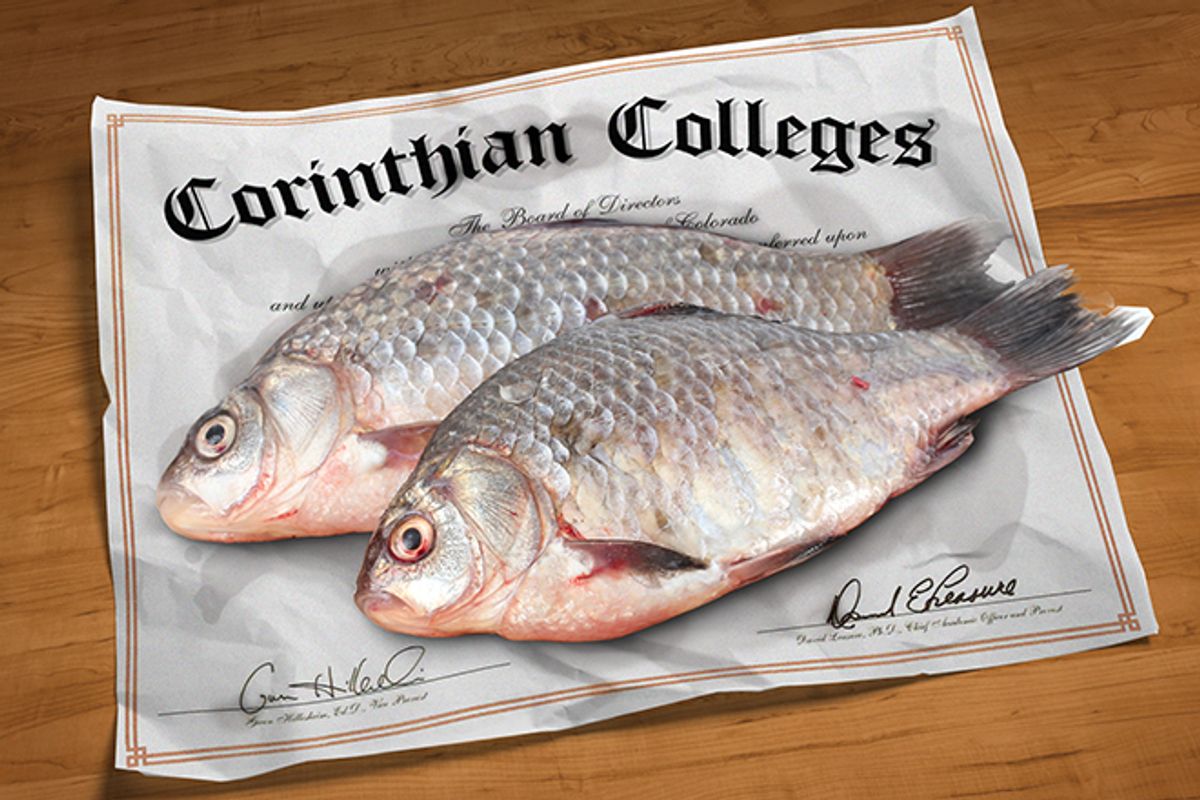

Corinthian Colleges, in that respect, is no different from any other career school. But in an industry where bottom-line considerations often trump devotion to educational achievement, Corinthian invites scrutiny. Over the course of its 17-year history, the company has attracted numerous lawsuits. Corinthian schools have recorded some of the highest default rates on student loans in the country, a worrisome fact for a company that derives nearly 90 percent of its revenues from government loans and grants. If you want to understand why the Obama administration has been so steadfast in its efforts to crack down on the for-profit industry, Corinthian is as good a place as any to start.

Founded in Irvine, Calif., in 1995 by five veterans of the vocational school business, Corinthian's strategy from the beginning was to purchase already existing schools and aggressively boost enrollment. The business plan was simple: grow, grow, grow. By 1998, Corinthian was ready for a public offering. Today, Corinthian is the fourth largest for-profit college in the U.S., with 97,000 students at 122 campuses distributed between the U.S. and Canada. At least half those students, says Jenkins, are enrolled in classes aimed at securing low-level jobs in the healthcare industry. In 2011, Corinthian recorded $1.9 billion in revenue.

Corinthian generates almost as much bad press as profit. In 2004 former students filed three separate lawsuits in Florida alleging credit transfer fraud, claiming that Corinthian misled students as to whether their credits would be accepted by other educational institutions. In 2005, Corinthian paid the Department of Education $776,241 for violations of student aid procedures at California's Bryman College. In 2007, reported the O.C. Register, Corinthian paid the state of California $6.5 million to settle charges of false advertising relating to allegedly overstating "the percentage of its students who obtained employment via its courses." Just three weeks ago, Corinthian revealed in a regulatory filing that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is investigating the company to "determine whether for-profit postsecondary companies, student loan origination and servicing providers, or other unnamed persons, have engaged or are engaging in unlawful acts or practices relating to the advertising, marketing or origination of private student loans.”

But perhaps the most embarrassing twist in Corinthian's recent history came earlier this year in California. In 2012, a new state law came into effect that denied colleges access to the state's Cal Grants financial aid program if the three-year student loan default rate at an institution exceeded 24.6 percent. Of the state's 165 for-profit schools, 67 failed the test. Eighteen of those 67 schools are owned by Corinthian. In fact, some of Corinthian's schools exhibited default rates of over 40 percent. None of California's public schools failed.

Corinthian's Jenkins acknowledged that in the past, Corinthian Colleges has had a problem with student loan default rates. But he said that in the last two years, Corinthian had addressed the problem, and rapidly brought down default rates across the entire Corinthian network from 21 percent to "6 or 7 percent."

Lauren Asher, president of the higher education research and advocacy think tank the Institute for College Access and Success, questioned whether Corinthian's sharp drop in default rates actually served the interests of students. She pointed to a May 3 conference call Corinthian held with investors, in which company executives acknowledged that much of the improvement resulted from "deferment and forbearance. "In other words, Corinthian students were being counseled on how to delay paying back their student loans, in order to avoid defaulting during the three-year window tracked by state and federal governments. However, the interest rates charged on student loans mean that the longer you wait to start repayment, the higher your debt load eventually becomes. According to U.S. Education Department data analyzed by Higher Education Watch, almost 75 percent of Corinthian students who had left their school within the previous four years had yet to pay down their student debt by a single dollar.

Corinthian's record on private sector student loan defaults is even worse, a fact that may explain why the CFPB has launched an investigation of the company. At Corinthian schools, students have been defaulting on private loans made directly by Corinthian itself to its own students -- so-called institutional loans -- at rates exceeding 50 percent.

And therein lies an interesting story. Government regulations limit for-profit schools from getting more than 90 percent of their revenue from government loans. The rationale is simple, as the Project for Student Debt observes: "If no one else is willing to pay for it, taxpayers should not be either." The rule was a response to the surging growth in the late 1980s of fly-by-night for-profits established solely to grab government loan money, and the original ratio was 85/15. Lobbying by the for-profit sector during the Bush administration (when the Department of Education was packed with for-profit veterans) weakened the standard to 90/10, but even that is still too strict for Corinthian executives, who have regularly complained about the rule in congressional testimony.

Complaints notwithstanding, Corinthian and other for-profit schools quickly found a way around the 90/10 restriction by bundling private student loans along with government aid in their financial aid packages for students. Private loans, usually offered by banks or Sallie Mae, a corporation that specializes in originating and servicing student loans, don't count against the 90 percent. So for every dollar in private student loan aid granted to a student attending a for-profit school, $9 in public aid become available.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, however, providers of private student loans exited the market, unable to afford the high default rates during a recessionary economy. In response, Corinthian and its for-profit colleagues lobbied Congress to pass a provision that allowed "institutional loans" made by the schools themselves to count toward the 10 percent part of the 90/10 rule. By 2010, Corinthian was lending its own students about $150 million a year.

For Corinthian, a 50 or even 60 percent default rate was acceptable precisely because the institutional loans make it possible to continue to access government funding. Even if Corinthian had to write off half of its annual disbursement of $150 million, the company more than made up for that loss in the revenue generated by government loans. As Sen. Durbin explained on the Senate floor last September: "The company is willing to take this loss of $75 million in private student loan defaults because these loans help ensure the federal loans and Pell grants will keep coming in to these students, despite the fact they are in over their head in debt and have nowhere to turn.”

Education activists like Asher point out that while the default rates don't hurt the bottom lines of the colleges, they are an ongoing disaster for students. The federal government has set up numerous ways to delay repayment of student loans or link payment rates to annual income. The private sector is less forgiving. A change in bankruptcy laws in 2005 ensured that private student loans, for example, cannot be discharged in bankruptcy.

Kent Jenkins defended Corinthian's institutional loan program with a refrain often heard from defenders of for-profit schools. Students at Corinthian, he noted, tend to have extremely low incomes, "did not thrive in traditional academia and are out on their own financially." They have few options. Corinthian, he said, trains these students for real-world jobs.

"The education that our students get is economically beneficial to them," said Jenkins, "and that is the way it should work."

Jenkins acknowledged that dropout rates in the for-profit sector can be high, but said the proper comparison for Corinthian, where most courses are under two years in length, is with two-year community colleges.

"We enroll a larger percentage of students that are high risk and minority," said Jenkins, "and we have a significantly higher graduation rate than community colleges do."

Corinthian's exact graduate rate numbers are in dispute. According to a report released by the Senate's Health Education Labor and Pensions Committee, chaired by Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, Corinthian schools have some of the worst withdrawal rates in the entire for-profit sector. Using data that Harkin's office asserted came directly from Corinthian, the Harkin report determined that 66 percent of Corinthian students who were enrolled in 2008-09 withdrew without graduating with an associate's degree by 2010, ranking Corinthian the fourth worst performer in the for-profit sector over that time period.

But even the Harkin report acknowledges that the completion rate data provided by publicly traded for-profit companies only accounts for first-time, full-time students, and doesn't include transfers or part-time students. And many of Corinthian's courses aren't designed to lead to associate degrees. A typical student might be enrolled in an eight-month "medical assistant" program. It's unclear where such courses show up in the statistics; according to Jenkins, the withdrawal numbers promulgated in Harkin's report do not include those students. According to Jenkins, during the time period studied by the Harkin team, 45,000 students graduated, and only 30 percent withdrew.

"The 66.5 percent number alleged by the HELP Committee is not only wrong, it has no apparent basis in fact," said Jenkins via e-mail.

(UPDATE: A Senate HELP Committee aide clarified that the 66.5 percent withdrawal rate applied specifically to Corinthian students enrolled in associate's degrees programs, and counted every student who completed those programs. According to the committee's data, of the 44,436 student who enrolled in associate's degree programs in 2008-2009, by mid-2010, 3,080 completed, 11,809 were still enrolled, and 29,457 had withdrawn.)

Critics of for-profit schools do concede that graduation rates for the sector as a whole are better than for community colleges. But they argue that doesn't mean that "outcomes" are better. Community college students tend to borrow much less from the government to pay for their education. (For-profit schools are estimated to cost five times as much as community colleges. The Harkin investigation, reported Bloomberg, found that "an associate’s degree in business from Corinthian’s Everest College in Florida costs $46,792, compared with about $6,453 for the same degree from Miami Dade College.") Meanwhile, nearly all for-profit students borrow to pay for most of their education. Which raises the question, are you really better off graduating from a for-profit school if you end up carrying so much debt that you are almost bound to default?

At a hearing discussing the financial outcomes of students at for-profit colleges held by the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions last June, Pauline Abernathy, a vice president at the the Institute for College Access and Success, testified that there is evidence that "completers at career colleges were much more likely to be in default than students who dropped out of public and nonprofit colleges. A study by three MIT researchers published in December 2011 summed up the following conclusions from the available data.

We find that relative to these other institutions, for-profits educate a larger fraction of minority, disadvantaged, and older students, and they have greater success at retaining students in their first year and getting them to complete short programs at the certificate and associate degree levels. But we also find that for-profit students end up with higher unemployment and “idleness” rates and lower earnings six years after entering programs than do comparable students from other schools, and that they have far greater student debt burdens and default rates on their student loans.

The high costs, withdrawal and student loan default rates all help explain why the Obama administration pushed last year to institute new "gainful employment" rules that would require for-profit schools to prove that acceptable percentages of their graduates were paying down their debt after graduation. However, even those rules were extremely watered down, say higher education watchers, after extraordinary lobbying efforts from the for-profit sector, including Corinthian Colleges. That's right: Corinthian spent money generated from taxpayer-funded student loans to pay for lobbying efforts aimed to weaken rules designed to ensure that students get a good education and taxpayers get their money's worth. If that doesn't send you screaming to your nearest publicly funded community college, nothing will.

Shares