In yesterday’s column, I discussed Chief Justice John Roberts’ decision upholding (almost all of) the Affordable Care Act. Now I’d like to discuss the world that almost came into existence – the vision of the four dissenters, Justices Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas and Alito, who wanted to throw out the entire statute. Roberts’ opinion has serious weaknesses, though the result was better than many expected. The dissenters, on the other hand, exhibited the highest virtue of any subordinate: They made the boss look good. With respect to the mandate, the Medicaid restriction, and the severability question, they devised arguments even weaker than those of the chief, proposing newly minted constitutional doctrines that make little internal sense and appear explicable only by a determination to eradicate every bit of a law that they just don’t like.

The biggest problem for the law’s challengers was always the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution. The court in 1819 rejected a claim that Congress could only carry out its powers by means that were absolutely necessary. Here is Chief Justice John Marshall: “The power being given, it is the interest of the Nation to facilitate its execution. It can never be their interest, and cannot be presumed to have been their intention, to clog and embarrass its execution by withholding the most appropriate means.” Compare the Scalia group:

There are many ways other than this unprecedented Individual Mandate by which the regulatory scheme’s goals of reducing insurance premiums and ensuring the profitability of insurers could be achieved. For instance, those who did not purchase insurance could be subjected to a surcharge when they do enter the health insurance system. Or they could be denied a full income tax credit given to those who do purchase the insurance.

When the “regulatory scheme’s goals” are enumerated, the dissenters forget to mention its overriding one: reducing the number of Americans who have no health insurance. (Later on in the opinion, they remember this and use it to show that Congress wickedly aimed to force all states to participate in the law’s Medicaid expansion.) If you add that one, then the two measures they propose are ridiculously ineffective compared with the one that Congress adopted. In fact, the only reason why the unpopular mandate got written into the law was that Congress and Obama were both reluctantly convinced that there was no other way that the statute could achieve its goals. They reached this conclusion on the basis of extensive analysis by the Congressional Budget Office and outside economists.

What basis have the dissenters for rejecting that reasoning? It’s impossible to know, because there are no citations to any empirical evidence whatever in the passage just quoted (which I have not edited). In other words, the dissenters are ready to destroy a carefully crafted congressional scheme on the basis of their own seat-of-the-pants intuitions about how the world works.

The dissenters go on to vindicate the liberties of those who “have no intention of purchasing most or even any [healthcare] goods or services and thus no need to buy insurance for those purchases.” Justice Ginsburg nailed this one: “a healthy young person may be a day away from needing health care.” Those who go without healthcare are not entirely unrelated to that market, any more than drunk drivers are entirely unrelated to other people on the highway. Both are imposing substantial risks on others – in the healthcare case, the risk of having to pay large amounts for an uninsured person’s medical bills.

Then there’s the question of when a condition on federal spending unconstitutionally coerces the states. Roberts’ answer was unclear, as I’ve already explained. The dissenters thought “the sheer size of this federal spending program in relation to state expenditures means that a state would be very hard-pressed to compensate for the loss of federal funds by cutting other spending or raising additional revenue.” It appears that Medicaid itself is unconstitutional, because “heavy federal taxation diminishes the practical ability of states to collect their own taxes.” The dissenters thought that, under the solution that the court adopted, “States must choose between expanding Medicaid or paying huge tax sums to the federal fisc for the sole benefit of expanding Medicaid in other States.” Of course, they would be put in the exact same spot if they chose to forgo all of their Medicaid funds, which was the sanction that the court invalidated. But the dissenters were too eager to strike down the whole law to consider that.

And that’s the scariest thing about the dissent. With both the mandate and the Medicaid expansion, they were prepared to strike down the law on the basis of constitutional rules invented for the occasion, and then to leverage that into wholesale destruction of the entire statute. This is the problem of “severability”: If part of a law is unconstitutional, how much of the rest of the statute has to be struck down as well? The answer depends on how much of it Congress would have passed had it known it could not enact the invalid part. The dissenters offer an elaborate argument that every last bit of the law is inextricably linked to the two parts that they would invalidate. I won’t follow them through every link of that chain – some of the logic is fairly stretched -- but will only note that they were even willing to strike down provisions that they conceded had nothing whatsoever to do with the offensive parts, such as a requirement that chain restaurants display the nutritional content of their food. Here’s their argument in full:

The Court has not previously had occasion to consider severability in the context of an omnibus enactment like the ACA, which includes not only many provisions that are ancillary to its central provisions but also many that are entirely unrelated—hitched on because it was a quick way to get them passed despite opposition, or because their proponents could exact their enactment as the quid pro quo for their needed support. When we are confronted with such a so-called “Christmas tree,” a law to which many nongermane ornaments have been attached, we think the proper rule must be that when the tree no longer exists the ornaments are superfluous.

In other words, if an unconstitutional provision gets tacked onto the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, and that provision has nothing to do with the rest of the law, the Court must invalidate the whole thing. They’re not serious. I confidently predict that this blunderbuss severability analysis, where a chip in the door jamb brings down the whole structure, will never be heard from again.

That’s the most disturbing thing about this opinion. It’s not just the poor reasoning, but the consistent pattern: lousy argument is piled upon lousy argument to reach the extraordinary conclusion that the entire law has to be struck down. This is Judge as Terminator: a machine that is programmed to kill its target and will blast through any obstacle to accomplish that. And this group came within one vote of victory. This opinion is important for what it tells us about what the law will look like with a couple of additional Republican votes on the court.

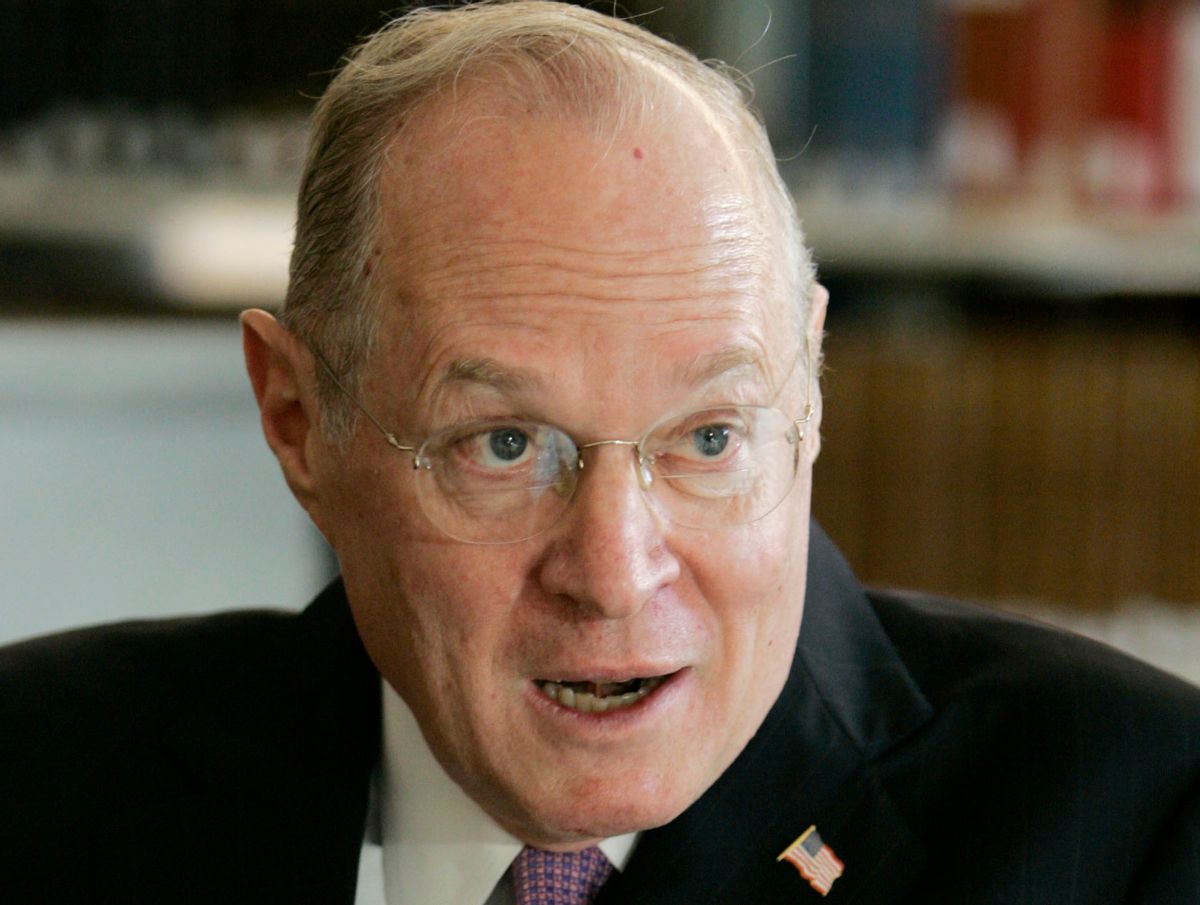

Anthony Kennedy has often been regarded as the moderate member of the Court, when he is actually just the swing vote who votes liberal on social issues. Based on his questions during oral argument, I expected him to vote to invalidate the mandate. I was surprised, however, that he was willing to go so far as to try to invalidate the entire law. Moderate is not le mot juste. His vote in this case shows a new extremism. I am not only referring to this case when I say that he has lost it.

Shares