"Tangle within tangle, plot and counterplot, ruse and treachery, cross and double-cross, true agent, false agent, double agent, gold and steel, the bomb, the dagger and the firing party, were interwoven in many a texture so intricate as to be incredible and yet true."

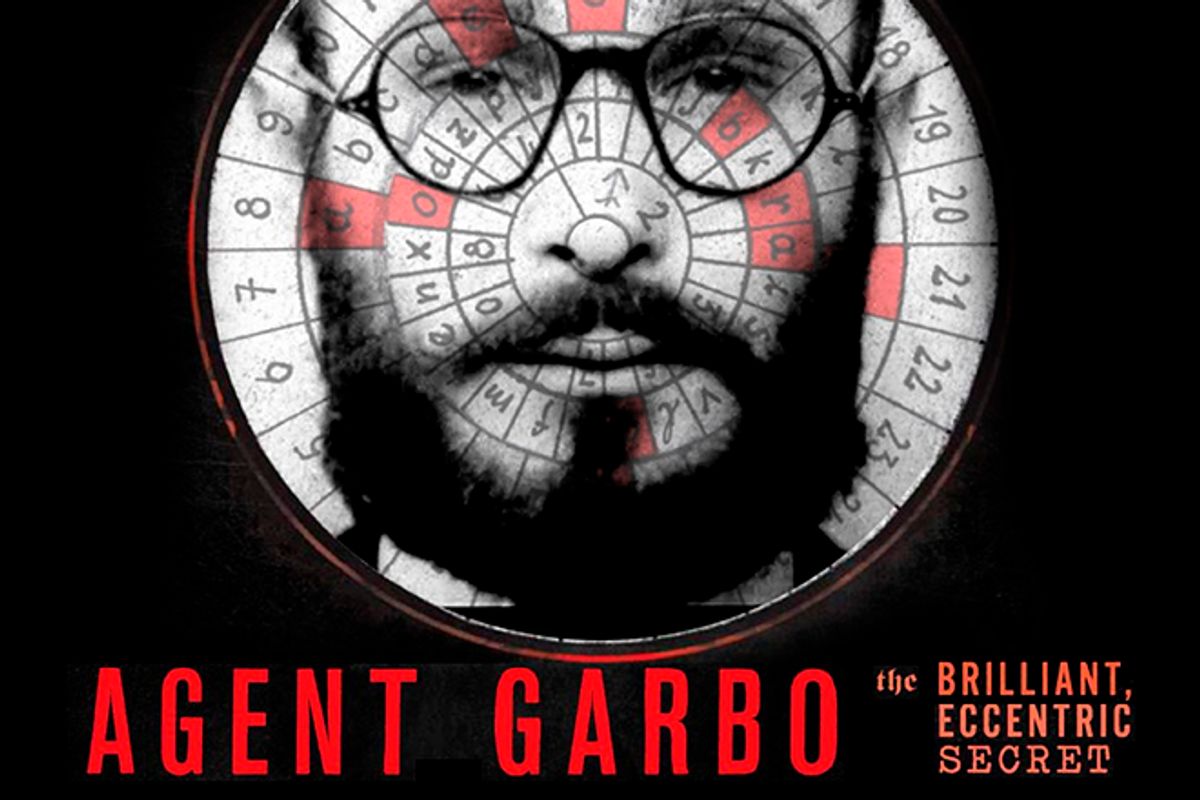

That's how Winston Churchill described the campaigns of deception practiced by British intelligence services during World War II, and it's also a pretty good characterization of the tale told by Stephan Talty in "Agent Garbo: The Brilliant, Eccentric Secret Agent Who Tricked Hitler and Saved D-Day." When, in 1984, a group of D-Day veterans gathered on Omaha Beach in Normandy for the 40th anniversary of the fateful invasion, some of them had heard of the double agent who was code-named Garbo, but even they were astonished to learn that the diminutive, balding gentleman being nudged forward by a journalist was the very same. One of the soldiers took him by the hand and introduced him around as "the man who saved our lives."

His name was Juan Pujol Garcia, a failed chicken farmer from Barcelona who became -- with his MI5 case officer, Tommy Harris -- the perpetrator of a massive ruse against the Nazis. J.C. Masterman, who ran Britain's Twenty Committee (as in XX, for double cross) during the war, remarked that what Pujol achieved was "for connoisseurs of the double cross ... The most highly developed example of their art." Pujol's greatest success was persuading the German High Command that the invasion of Normandy was essentially a feint, the prelude to a major attack on Calais to the northeast. This caused them to withhold troops from the battle, a mistake that both Erwin Rommel and Dwight D. Eisenhower regarded as decisive to the Allies' success.

This isn't the first book about Pujol. (He wrote his own memoir with Nigel West, the historian who discovered him living in Venezuela in the 1980s.) There have even been a couple of documentary films. "Agent Garbo" can't promise revelations. Talty, knowing this, pours his energy into the storytelling, which attains just the right balance of sophistication and pulp. Col. Baron Alexis von Roenne, the chief German military intelligence officer in the West, for example, is invariably tagged as "gray-eyed," rather (hilariously) like the goddess Athena in the Odyssey. Yet the intricacies of the wide-ranging Garbo operation are laid out with blessed clarity. Aficionados might quibble here and there, but so what? This is a true-spy yarn for the common reader.

Novice freelancers can also take inspiration from Pujol's grueling start in the espionage business. He had no training, no teacher, no received knowledge of tradecraft and a hell of a time convincing the Allies to give him a chance. He was a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, from which he emerged without much respect for either side, and his primary ideological conviction seems to have been a hatred of bullies and murderers. He may have been drawn to spying because of his taste for playacting as well as his dislike of Hitler. He told the British that his intentions took form after his brother witnessed a Nazi massacre of some Spanish villagers, but this turned out to be lie. Several Britons who worked with him confessed that they never fully understood his motivation for helping them. But he was really, really good at what he did, and that's often motivation enough.

Talty likens the Garbo operation, and the various other deception operations it fed into, to the production of Hollywood movies. Pujol was the ultimate writer-actor-director, inventing 26 entirely fictitious agents scattered throughout Briton and purportedly eager to aid the Nazi cause, from the treasurer of the (nonexistent) World Aryan Order to a disgruntled Gibraltarian waiter to a love-starved secretary in the Cabinet Office. Each had an elaborate back story and agenda. Garbo/Pujol, who was eventually set up with a wireless radio in London, kept his German handlers stoked with tales of his sources' trials and peccadilloes, spinning a narrative tapestry so elaborate that the enemy couldn't help but believe in it. The Nazis awarded him the Iron Cross, and his cover was never blown.

Since Pujol's was essentially desk work, Talty beefs up the book with yarns from other celebrated British spies, such as the swashbuckling Serb code-named Tricycle and the abrasive David Strangeways, who revamped the faltering Allied plan to trick the Germans about the site for the D-Day invasion. That plan, Operation Fortitude South, entailed a mind-bogglingly elaborate array of ruses: inflatable tanks and carriers, fields of fake campfires, contraptions made from car headlights designed to look like airplanes landing at night, wind machines, sound effects, planted "customers" demanding maps in bookstores throughout Europe, even a Field Marshal Montgomery impersonator. For his part, Garbo managed to persuade the Germans that an entirely imaginary million-man army -- the First United States Army Group -- was poised to strike strategic targets.

But perhaps Pujol's most outrageous gambit was perpetrated against his own wife, Araceli, a tempestuous beauty who resented living in grim, wartime London with a husband who was completely preoccupied with his work. In her fury at being unable to return to Spain, she made rash threats to expose Garbo. To scare her into compliance, MI5 concocted a story in which Pujol punched out a British official who dared to question her loyalty and was locked up in a particularly nasty prison. Araceli visited the fake prisoner there, and was convinced that his life hung by a thread -- specifically the thread of her good behavior. The trick worked.

For many years after the war, few knew Garbo's real name and most of those thought he was dead. Pujol wanted it that way, supposedly in fear of reprisals from ex-Nazis and their sympathizers. He remains something of a cipher, however, as Talty probes the possibility that he was avoiding dealing with his first family; his children by Araceli believed their father had succumbed to malaria in West Africa in 1948. He ran a tourist hotel in Venezuela, showing movies to the village children in the establishment's little theater and raising a second family with a much younger wife. If not for Nigel West, he might have died in obscurity. And now, thanks to Talty, he's further immortalized in a book that reads like just the sort of ripping story he loved best.

Shares