In a gallery at London’s Tate Modern, a slim man in dapper black business-casual clothes is pacing, grasping his cell phone (also black, though the grasping makes his knuckles very white). Mr. Biz-Cas is oblivious to the museum’s temple of hush. He stalks past people and paintings, ignoring the white/cream dots in a grid and a taxidermied dove rising in a gold frame. “Can you transfer 8,000 pounds to my current account?” he asks someone on the other end of the line. It’s shocking to hear – in an art gallery at that.

Welcome to the Damien Hirst retrospective, which might be called Damien Hirst LLC.

A minute later, Biz-Cas slips into another gallery, the final room of the show. Only the work is hung too close together. It doesn’t have the same space to breathe as in the rest of the exhibit, where white walls provide not just breath but a patina of Art, of culture. Here, vitrines hold china and skateboards and a skull that’s been twirled about on a turntable with house paint dripped from above in a psychedelic pattern. It takes a few seconds to realize this is not the exhibit. This is the shop.

People bend over the prints, and in that art-institution whisper they discuss which is more expensive. All bear large signatures because that’s what you’re buying, Hirst’s name. There are also deck chairs for sale, Supreme skateboards of Hirst’s spot paintings and umbrellas of his spin paintings. You can get wallpaper and wrapping paper and charm bracelets of silver pills and silver cufflinks of silver pills; and after so much stuff like that in cases in the exhibit, everything from pills to cubic zirconia and cigarette butts, this room looks like an exhibit, too. The china set is £10,500, a skateboard £480, and that painted plastic skull goes for more than £36k. Just to translate, that is more than I earn in a year.

[caption id="attachment_12954021" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="Does that look like a year's earnings to you? Or am I just grumpy and conservative? Image from the Daily Telegraph."] [/caption]

[/caption]

Biz-Cas strides up to his companion, also in black, and a woman with a three-ring binder. She’s taking their details and card information. Behind the counter at the cash register, two other employees smile broadly. The woman nods their way with a subtle tilt of the head. This is a ballet of nods and smiles between the three, because money is being made and exchanged. Biz-Cas is now “can-you-please-sign-here-sir” parting with £9,000 of his money (around 15k USD to you and me) for a limited-edition Hirst print sprinkled with diamond dust so it glitters like pixie dust. Only this is not Peter Pan. I am not sure what illusion he is buying here, or that anyone could truly believe this print has value, but he does. He buys. He pays. Plastic is swiped. In seconds he and his companion own the print. However, “it will take four weeks to frame,” the assistant nods again. Giddy with the purchase (and how else can you feel after spending such money on diamond dust and a signature?) the two men ask where she is from. “Italy,” she says and the men rush to ask where. The three of them share in a joint moment, their money, their thing, her selling, the print … The elation is palpable across the room, and it’s hard not to stare, puzzled, fascinated by this display.

It’s all too easy to diss Damien Hirst. Doing so makes me feel like that bastion of British conservative middle-classness, the Daily Mail. But, something disturbs me in his work. Take the eleven Gagosian Galleries around the world this winter filled with hundreds of Hirst’s spot paintings. Apparently anyone who went to see all of them in every Gagosian got a signed spot painting as a reward for such herculean efforts, not to mention the air miles accrued. These affectless grids of colored dots are made with house paint, and all but a very, very, very few are painted by his assistants. Not that I need an artist to make his (or her) own art. Not that I’m even sure what the “aura” of an artist’s actual hand means now, let alone his signature. (I do wonder if Hirst has actually signed those prints — the signatures are very, very big.) Not that I’m against money, either, but having so much of it on display makes it seem like that is the message.

In 2008, just as Lehman Brothers was failing, he had a two-day sale at Sotheby’s and bested the auction house’s estimates of what the sale would bring in by a considerable amount. The total haul was over $200 million. The artist is himself worth about $340 million. Here in the Tate there’s so much gold and diamonds it’s dizzying, like eating too much ice cream, followed by cake and chocolate. It reminds me of the one time I went to Buckingham Palace (I wanted to see the queen’s outstanding Vermeer, “The Music Lesson,” only available to the public during the one month she opens her London home while she is elsewhere, typically in Scotland). Everything in Buck House — the furniture, sofas, chairs, walls, tapestries, frames, paint — was gilded. There was so much gold, I left feeling nauseous, and it was hard to see a single painting. They were hung salon style, so close together they seemed a teeming mass of gold curlicued frames.

Consider this a palate cleanser. Vermeer's "The Music Lesson" — aka, a lady at the virginals with a gentleman.

In London, though, this is the summer of diamonds. Of jubilees and gold. Of the Olympics. So the Tate is done up; there’s tat in the store and Damien Hirst. To be fair who else would they have? Who else could they? He’s Britain’s most famous contemporary artist, and the crowds have been pounding in at 4,000 people a day.

The show is part of the “Cultural Olympiad,” which is being billed as the “largest cultural celebration in the history of modern Olympics.” For this, Britain is dusting off its greatest (or, at least, most famous), so you get the likes of Lucian Freud at the National Portrait Gallery (nothing to sneer at there) and Hirst at the Tate. Many of these shows and plays and concerts would have happened anyway, but they are now grouped under the rubric of the Olympics in part to grab some of the Games’ excitement as well as government money set aside for them.

Hirst went to art school at Goldsmiths in the late Eighties. At that point, it was the center for training British conceptual artists (which the Daily Mail did just call “con art”). While there, he put on Freeze, a show of his and his school friends’ work, in an abandoned warehouse space, not far from where the Tate Modern is now. That was nearly a quarter of a century ago and a different era in urbanism and gentrification. Freeze was a generational stake in the ground. People often say they were there, even if they weren’t. Others’ memories are hazy from too much pot, coke, and – for those riding the seam between art and raving – E. The show introduced a slew of artists now commonly called YBAs, others of whom are having retrospectives this summer too. (Jeremy Deller is of the same generation, but about as far from a YBA as you can get. For the Cultural Olympiad, he is doing a bouncy-castle version of Stonehenge that’s touring the country.)

Hirst is the son of a used-car salesman, which might explain his fascination with wealth. His dad abandoned the family. The young Damien was trouble in school. He went from construction work to art school, all fine as back story goes in the art world, where you don’t have to come from a rarified past to make it. He’s got a bad boy reputation and Bono glasses, plus a square jowly face that gives him the look of a London cabbie or, I often think, a butcher. He has transcended the art world by making videos for pop stars and songs for the World Cup, such as the now forgotten “Vindaloo.” Made with Blur’s bassist and the comedian Keith Allen, it mimed football chants and Britain’s love of curry. The song made it to number 2 in the pop charts during the ’98 World Cup.

Hirst has redefined art and made it accessible, defying the rarified stance of museums and galleries. He’s even cut the art bit from “art star” to become simply a star. Because he makes so little of his output, his work is about branding as much as art, begging the question, What’s in a name? What’s that name worth? Just as brands try to trade on familiarity, creating brand extensions based on their existing products, so too Hirst. He works his themes hard, pounding them over and over again: death, rebirth, drugs, taxonomy, taxidermy (the latter three are simply stand-ins for death and rebirth). Oh, and money, too, which I suspect is also a kind of death. In his love of lucre (and his love of lucre in his work), the work itself starts to seem sealed in a gilt coffin. I truly think the shop is an extension of Hirst’s oeuvre, that it’s as much an installation as the slick, sterile pharmacy he re-creates in the show.

Perhaps all you need to know about the Hirst exhibit is what the Tate’s own director Sir Nichola Serota said recently in the New Yorker: “I have no doubt at all that Hirst’s early work is very important. Time will tell whether it survives, but I believe it will.” Calvin Tomkins didn’t question this. After all, the article was a profile lionizing Serota, but what he was saying — what Tomkins didn’t include — was this is the art world’s damning of Damien. Serota is saying all that Hirst’s later work is really crap and tat, nothing more than smoke and mirrors (and there are a lot of both smoke and mirrors in the show). But what would it say about Serota for him to be hosting a major retrospective of an artist he didn’t actually think particularly good? Or, one we all admit is caning it? Even Hirst said about the skull in the store: “Maybe on eBay you might be all right for a bit.”

The show is chronological, and like Sir Nick said, the early work is good and important. It’s also moving because it’s still rough and hasn’t yet been worked over to be smooth and seamless, sterile in its perfection. My favorite piece in the show is a grouping of cardboard boxes in the first room about 2/3 up the wall in the corner. The boxes are in a Rietveld-like pattern, all painted with bold gloss house paint. Which later becomes a thing for Hirst. Much of the work is irritating and obvious. “Lapdancer” is a case filled with stainless steel surgical implements. The piece is owned by Peter Marino, architect to Louis Vuitton and Chanel boutiques around the world. The giant ashtray “Crematorium” is filled with cigarettes and potato chip wrappers. It even smells of butts.

[caption id="attachment_12953981" align="alignleft" width="300" caption=""Boxes." And, no snark. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2012"] [/caption]

[/caption]

“Sinner,” the very first of his many, many drug cabinets, is filled with his grandmother’s pills and salves she left him when she died of lung cancer. There’s the morphine and rubber gloves, digoxin (purified from foxglove to treat heart conditions), and chlorpromazine (generic thorazine for schizophrenia and dementia). The packaging is stained with use; the labels with her name on them are peeling. Frailty is implicit, and the idea of keeping death at bay seems sad and personal.

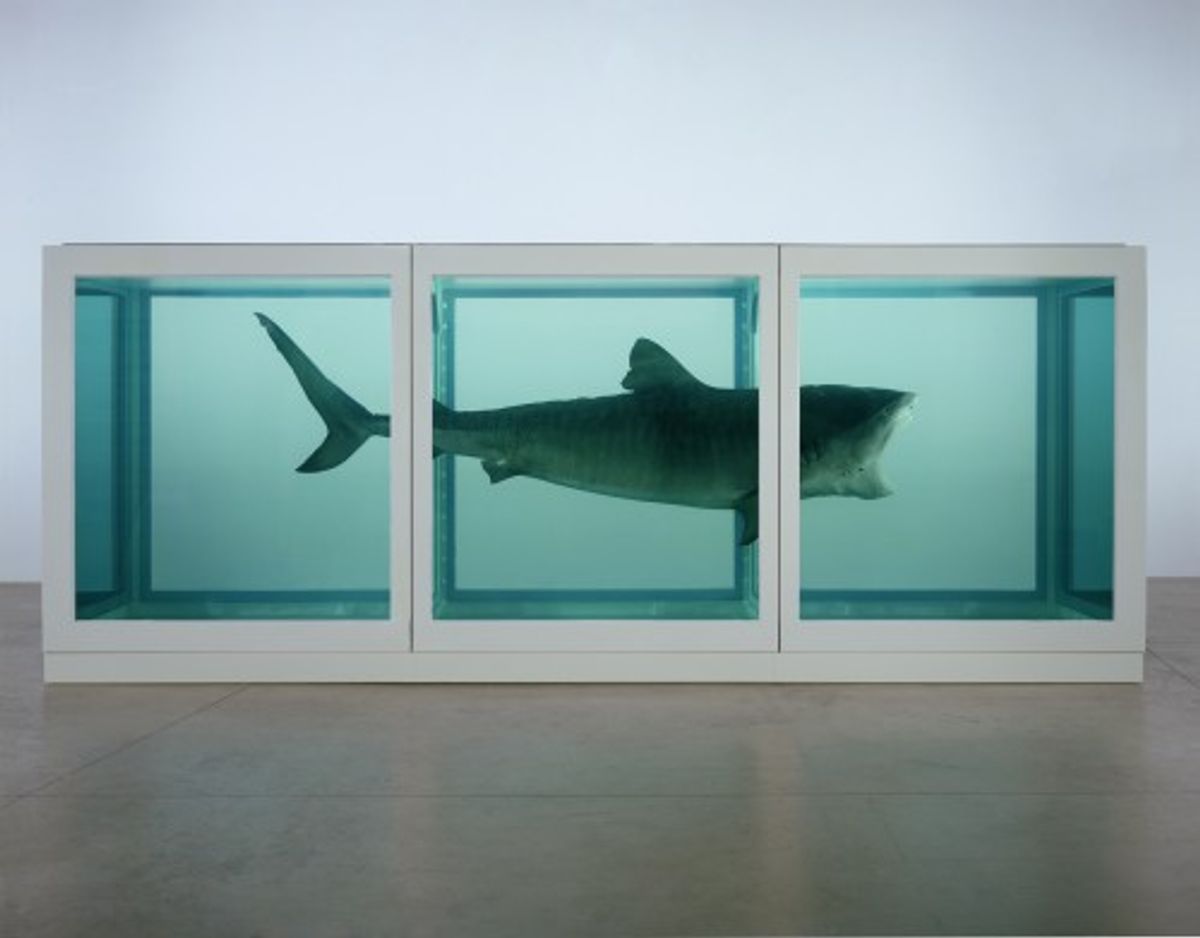

Or, there’s the early evolution of the spots, first painted on the bottom of kitchen pots and pans, the pans themselves perfect circles. Butterflies later become Hirst’s stock in trade, with paintings made of actual butterfly wings like so much Nabokovian longing. They’re luminous, yes, stuck into shapes like stained glass windows. At first, though, they are literally stuck into gloss paint on canvas. It’s cruel and hideous, but painfully moving. Of course, it’s about death and rebirth. There are enough flies and maggots in the museum to keep CSI in business for the next decade. Oh, and there’s the mastery of death by staring a formaldehyded shark in its face. Called “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living,” the piece was financed by Hirst’s early patron, ad-guy Charles Saatchi. Yes, it’s about death and preservation (obviously) but it didn’t defy decay itself. Now the piece looks a bit sad, like a rubber shark, and the formaldehyde has to be changed regularly. It starts to go cloudy.

[caption id="attachment_12953991" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="Does "The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living" make you think of Death? Or Jaws?"] [/caption]

[/caption]

The themes, however, are so very clear, repeated as often as they are, that Hirst makes conceptual art accessible (and I certainly don’t believe it should be purposefully obtuse). In his hands it becomes stiff and loses its lyricism, while the money and celebrity provide their own self-reinforcing allure.

Hirst has said, “All these gold paintings and gold and diamonds, it’s definitely all about feeling like Midas.” And while Midas might have turned everything he touched into gold, he also ended up starving and lonely in a prison of his own creating. In talking about his work, Hirst is also prone to the inane, saying things like, “In an artwork, I always try to say something and deny it at the same time.”

It’s all everything and nothing and empty in the end, as the show literally ends in that room just before the shop with overwrought metaphors: the dove and dots, white on white. The Christian theme is patently obvious, yet he still needs to bang us over the head with it.

My favorite moments in the show had little to do with Hirst and everything to do with people. One: A little girl all in pink ran screaming “baa!” across the gallery to the case with the embalmed dead lamb, called “Away From the Flock.” In the next room, a boy clung open-mouthed to the shark’s glass like he was at an aquarium. There’s a room full of live butterflies, the first time they’ve been shown since the early 1990s. To get to them, you have to first cross a room with a table that has ashtrays at all four corners. (Hirst has called smoking a miniature version of the life cycle.) The butterflies have hatched from pupae attached to canvases. Presumably the insects will mate and die and hatch all over again on the gessoed surfaces, turning them into a painting of sorts. Something magical happens here, though, as the butterflies land on people’s shoulders, but it’s no more special or entrancing than a butterfly house. Plus, the show is up for months; does the museum have to replace the butterflies? What about the dead cow’s head with the flies? These are questions I ask the press office, but I never get answers. I’m also curious about how much money the store is generating. Again, no word.

[caption id="attachment_12953994" align="alignleft" width="300" caption="The Hirst Broom Cupboard, photo by Simon Li"] [/caption]

[/caption]

Late on a Friday night a week before I saw the show, I stumble into the Tate’s Turbine Hall, the massive cathedral of a space where electricity was once generated for London. Now it’s where you can see works like Miroslaw Balka’s entirely black room and ponder an extreme existential nothingness, which in a museum with a crowd of people becomes transcendent. Other artists have used the space to simulate weather and create a giant fissure in the floor. Ai Weiwei littered it with sunflower seeds, a commentary on capitalism and China, individuality and production. A small black cupboard holds a single piece of Damien Hirst’s, a diamond encrusted human skull. I’ve had sushi and beer, and I am, if not drunk, at least tipsy. My expectations are low. After five minutes on line, nine others and I are let into the blackened room. In the middle is the skull. No plastic here. Hirst is the richest artist in the world; he is the 1%, and the skull is free to see. It’s mesmerizing – a freaky, glittering meditation on death. It’s the Mexican Day of the Dead meets a Dutch master’s memento mori. I’m shocked and stare open-mouthed like the kid with the shark. I’d assumed the skull would be tacky, dismissible. I was ready to laugh it off. Yet, there is a moment with the skull that feels private, transfixing, even as everyone around is saying, “Are those Swarovski crystals?” and, “Do you think it’s real and stuff?” And stuff, yes. Here, it’s nearly psychedelic. The diamonds sparkle in ways I never imagined they could. (I don’t see enough diamonds in my life.) They draw you in, make you want to stare, so you stand before it entranced, contemplating death. It’s both obvious and memorable. It’s worth $80 million. And, it’s gone now. It was only up until the end of June.

[caption id="attachment_12953996" align="alignleft" width="299" caption="Does that look like $80 million to you? "For the Love of God" (yeah, that's the name). By Joanna Penn"] [/caption]

[/caption]

Shares